「私の青春時代と恋愛――私は恋愛とともに成育する」――佐藤春夫の「わが恋愛生活を問はれて」 [魂と霊 Soul and Spirit]

のちに『退屈読本』におさめられる佐藤春夫 (1892-1964) のエッセー「わが恋愛生活を問はれて」の初出は『婦人公論』大正10 (1921) 年10月号(初出時のタイトルは「私の青春時代と恋愛――私は恋愛とともに成育する」)。

考えへ込んでゐては結局言へない。フランクに言ふより外に手がない。で、僕の霊の上に影を落としてる女は五人ある。

に始まるが、佐藤春夫の霊の上に影を落としている「女」は生身の女ではない。――

第一。これは拙著「殉情詩集」のなかに歌はれてゐる「少年の日」である。要するにお伽話〔お伽噺に傍点(`)〕で、相手は僕にとつて先づお伽話の王女だ。

〔・・・・・・〕

第三。これは一部の小説〔小説に傍点(`)〕だ。

第四。これは第三のものよりも多く小説〔小説に傍点(`)〕だ。どうも少々ストリンドベルヒの縄張りだ。

第五。小説でもなければ抒情詩でもない。言はば、叙事詩だ〔叙事詩に傍点(`)〕。いや手の込んだ押韻戯曲だ。だがこれ以上を今は問はないでくれ。ここにベルレイヌにこんな詩がある――

もっとも、過去の自作はそれぞれ背後に女性を秘めているということが研究者からは指摘されていて、第一は大前俊子(中村俊子)、第二〔「これは同じく「殉情詩集」のなかの「ためいき」だ。これは要するに事件そのものが叙情詩だ〔叙情詩に傍点(`)〕。僕は足かけ三年思つてゐて、その人と口を利いた事は十ぺんとはない。もう八年ぐらゐ前のことだ。だが、若し私が今この人と二人きりで出会ふやうなことがあつたら、やはりいくらか胸がどきどきするだらうと思ふ。この人は、私に、常に人生になければならない憧れの要素を私の心のなかへ沁み込ませて消えていつた――ちやうど暮春の夕ぐものやうに美しく。」〕は尾竹ふくみ(安宅ふくみ)、第三は遠藤幸子(川路歌子)、第四は米谷香代子、第五は千代夫人(元 谷崎潤一郎の妻)。やれやれ。

そう言って、第五の一節に続いて引用されるポール・ヴェルレーヌ (1844-96)の詩――

たつたひとりの女の為めに

私の霊はさびしい。今ではやうやう忘れはしたが

私の心も霊もどうやらあのひとから離れては来たが

しかも私はあきらめられぬ。〔・・・・・・〕

たとえば女の子に(春夫はもちろん女じゃないけれど)「私の心はさびしい」といわれたならりりぃの「心が痛い」と同じくらいには容易に共感できるかもしれないけれど、「私の霊はさびしい」といわれたときには、ちょっと引いてしまうのが現代の日本語ではないかしら。そして、春夫訳のヴェルレーヌの第2連は「私の心も霊も」と別扱いしているのです。

要するに以上すべての彼の女たち〔=彼女たち〕に幸あれ。私は時に彼等の或る者を憎むことがあるが、然し憎(し)みは消えやすい。愛はどこかへ霊のうつり香になつて残る。私も彼女たちの誰からも、仇敵と思はれてゐようとは信じられない。私は私の青春をかくもむごたらしく斬り刻んだ私の運命を愛しよう――さうするより外には仕方もない事だ。多謝す、私の故人たちよ、おん身たちは兎に角私に人生を与へた。或る場合には私の理智が欠けてゐた。或る場合には私の意志が弱かつた。しかし私はいつも一途に思ひ込みはした。自他を欺き弄んだことは決してない――さう自ら信ぜられることが私の慰めである。私はいつかは血をもつてこれらのすべてを描き出すだらう。

あー、故人となったから霊なんだ、と思うとさにあらず、霊が彼女らなのではなくて、彼女らが僕の霊の上に影を宿しているのです。僕の身も心も霊もさみしい。・・・・・・おまえ誰やw。

次元 Dimension (1)――バーネットの『白いひと』 [The White People]

なんか、前から、フォントについては四苦八苦しています。フォントの選択がブログ作成ページにはない。でもワードからコピペすると、スタイル情報とかで重たくなってしまうらしい。でも・・・・・・やっぱりほんとは英語の引用符とかシックスナイン(' ') ("") じゃなくて(‘ ’) (“ ”) で記したい、みたいな気持ちはあります。

フランセス・ホジソン・バーネットの『白いひと』 Frances Hodgson Burnett, The White People (New York: Harper, 1917)。

長らく尊敬してきた作家マクネアンとロンドンで知り合った語り手イザベル・ミュールキャリーは、マクネアンの母親とも親しくなります。マクネアン夫人といるとイザベルはいろいろなものが違って見えるようになります。夫人のほうは、イザベルが実体をもっていて溶けて消えてしまうことがないのを確かめるかのように、ときどき触れたりして、いつも自分のそばに置いておこうとするのでした。マクネアン家の庭で3人は黄昏から夜の闇に包まれるまで一緒に座って話をする日々を送ります。

I don’t remember just how she began, and for a few minutes I did not quite understand what she meant. But as she went on, and Mr. MacNairn joined in the talk, their meaning became a clear thing to me, and I knew that they were only talking quite simply of something they had often talked of before. They were not as afraid of The Fear as most people are, because they had thought of and reasoned about it so much, and always calmly and with clear and open minds. By The Fear they meant that mysterious horror most people feel at the thought of passing out of the world they know into the one they don’t know at all. How quiet, how still it was inside the walls of the old garden, as we three sat under the boughs and talked about it! And what sweet night scents of leaves and sleeping flowers were in every breath we drew! And how one’s heart moved and lifted when the nightingale broke out again! “If one had seen or heard one little thing, if one’s mortal being could catch one glimpse of light in the dark,” Mrs. MacNairn’s low voice said out of the shadow near me, “The Fear would be gone forever.”

“Perhaps the whole mystery is as simple as this,” said her son’s voice “as simple as this: that as there are tones of music too fine to be registered by the human ear, so there may be vibrations of light not to be seen by the human eye; form and color as well as sounds; just beyond earthly perception, and yet as real as ourselves, as formed as ourselves, only existing in that other dimension.”

There was an intenseness which was almost a note of anguish in Mrs. MacNairn’s answer, even though her voice was very low. I involuntarily turned my head to look at her, though of course it was too dark to see her face. I felt somehow as if her hands were wrung together in her lap. “Oh!” she said, “if one only had some shadow of a proof that the mystery is only that we cannot see, that we cannot hear, though they are really quite near us, with us—the ones who seem to have gone away and whom we feel we cannot live without. If once we could be sure! There would be no Fear— there would be none!” (Frances Hodgson Burnett, The White People, ch. 6 “The Fear,” pp. 61-63) (私はマクネアン夫人がいったいどういうふうに語りだしたのか覚えていません。そして、数分間は夫人の言っていることがまったく理解できませんでした。けれども、夫人が話を続け、マクネアンさんもその話に加わって、ふたりの語る意味が私にもはっきりしてきました。そしてふたりはかねてしばしば語ってきたことをごく簡潔に話しているにすぎないことがわかりました。ふたりは、たいていの人がおそれるようには<恐怖 The Fear>をおそれてはいませんでしたが、それは、ふたりがいつも冷静かつ明晰で心開いて<恐怖>について考えたり論じたりしてきたからなのでした。

<恐怖>によってふたりが意味していたのは、たいていの人が、自分たちの知る世界から、まったく知らない世界へと移行することについて考えたときに感じる神秘的な恐ろしさのことでした。

私たち3人が木の枝のしたに座ってそのことについて語りあったときの、古い庭の壁の中は、なんと静かで、なんと落ち着いていたことでしょう! そして、私たちが息をするごとに、葉や眠る花の、なんて甘い夜の香りがしたことか! そして、ナイチンゲールが再びさえずりだしたときに心がどれほど動かされ、高まったことか!

「もしも、ほんのちいさなことを見るか聞くかしたなら――もしも地上的な存在である人間が、暗闇のなかに光の一瞥を捉えることができたなら」とマクネアン夫人の低い声が私のそばの暗い影から言いました、「<恐怖>は永遠に消え去るでしょう。」

「もしかすると、神秘はこういうふうに単純なのかもしれない」と彼女の息子の声。「こんなふうに単純なのかも。人間の耳に留められるにはあまりに繊細な音楽の音があるように、人間の目では見られない光の振動があるのかもしれない。音だけでなく、形や色も。ただ地上的〔earthly 肉体的〕知覚を超えていて、それでも私たち自身と同様にリアルで、私たちのように形成され、あの別次元に存在しているだけというような。」

マクネアン夫人の答えには、ほとんど苦悩の調子とでもいうような激しさがありました。その声はとても低かったのですけれど。私は思わず顔を向けて夫人を見ようとしました。もちろん暗すぎて顔は見えなかったのですけれど。それでも私はひざの上で両手が握り締められているような感じがしました。「ああ!」と彼女は言いました。「神秘というのが・・・・・・彼ら――逝ってしまったけれども一緒にいてくれなければ生きていけないと私たちが感じる人たち――が実は私たちのすぐそばにいるのに私たちには見られず聞けないということが神秘なのだ、という、ほんのかすかな証拠でも得られれば。一度でも確信を持てたなら! <恐怖>はなくなるでしょう――すっかりなくなるでしょう!」)

ここで「次元 dimension」という(概念とまではいえずとも)コトバがもちこまれるのは、時代的なものがあるのかしら。とちょっと調べてみたい気になりました。(ああ、今回の主旨は、ただこの一節を書き留めることにこそあります。)

「エドガー・A・ポーの死」――N・P・ウィリスのポー追悼文 "Death of Edgar A. Poe" (1849) by Nathaniel P. Willis [Marginalia 余白に]

ニューヨークの新聞・雑誌編集者だったナサニエル・P・ウィリス Nathaniel Parker Willis, 1806-67 は1844年にポーを『イヴニング・ミラー』紙の "paragrapher" (一種の編集助手――ウィリスの文章だと "sub-editor")として雇っていて、3つほど歳のちがうポーと親交がありました。手紙のやりとりも続けていました。ポーはエッセイ「ニューヨーク市の文人たち」や「直筆署名」でウィリスをとりあげていることはポー事典も指摘しています。でも指摘していないことだけれど、ウィリスがあてこすられている短篇小説もいくつもあるみたいです。そのあてこすりは、しかし、友人関係を壊すほどのものではなかった(とはウィリスは受け止めなかった)ようです。

ポーが1849年の10月7日に亡くなって、文学的遺産管財人となるルーファス・ウィルモット・グリズウォルド Rufus Wilmot Griswold, 1815-57 は、ポーに対する誹謗中傷をしだいに募らせていくわけですけれど、N・P・ウィリスは、グリズウォルドを中心とする人身攻撃に異を唱えたひとりでした(女友達のセイラ・ホイットマン――「イタコのセイラ」参照――がもうひとり)。

1849年10月20日号の『ホーム・ジャーナル Home Journal』でウィリスはポーの追悼文を書きますが、グリズウォルドの早速の中傷文章を引用して反駁しています。――

The ancient fable of two antagonistic spirits imprisoned in one body, equally powerful and having the complete mastery by turns-of one man, that is to say, inhabited by both a devil and an angel seems to have been realized, if all we hear is true, in the character of the extraordinary man whose name we have written above. Our own impression of the nature of Edgar A. Poe, differs in some important degree, however, from that which has been generally conveyed in the notices of his death. Let us, before telling what we personally know of him, copy a graphic and highly finished portraiture, from the pen of Dr. Rufus W. Griswold, which appeared in a recent number of the Tribune:

“Edgar Allen Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore on Sunday, October 7th. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it. The poet was known, personally or by reputation, in all this country; he had readers in England and in several of the states of Continental Europe; but he had few or no friends; and the regrets for his death will be suggested principally by the consideration that in him literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars. (エドガー・アランポーが亡くなった。10月7日の日曜日にボルティモアで死去。この通知は多くの人々を驚かせるだろうが、それで悲しむ者はごく少ないだろう。 詩人は、個人として、また評判によって、この国じゅうに知られていた。イギリスと、ヨーロッパ大陸のいくつかの国に読者をもっていた。しかし、彼にはほとんど、あるいはまったく友人がいなかった。・・・・・・)

“His conversation was at times almost supramortal in its eloquence. His voice was modulated with astonishing skill, and his large and variably expressive eyes looked repose or shot fiery tumult into theirs who listened, while his own face glowed, or was changeless in pallor, as his imagination quickened his blood or drew it back frozen to his heart. His imagery was from the worlds which no mortals can see but with the vision of genius. Suddenly starting from a proposition, exactly and sharply defined, in terms of utmost simplicity and clearness, he rejected the forms of customary logic, and by a crystalline process of accretion, built up his ocular demonstrations in forms of gloomiest and ghastliest grandeur, or in those of the most airy and delicious beauty, so minutely and distinctly, yet so rapidly, that the attention which was yielded to him was chained till it stood among his wonderful creations, till he himself dissolved the spell, and brought his hearers back to common and base existence, by vulgar fancies or exhibitions of the ignoblest passion.

“He was at all times a dreamer―dwelling in ideal realms―in heaven or hell―peopled with the creatures and the accidents of his brain. He walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayer (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned, but) for their happiness who at the moment were objects of his idolatry; or with his glances introverted to a heart gnawed with anguish, and with a face shrouded in gloom, he would brave the wildest storms, and all night, with drenched garments and arms beating the winds and rains, would speak as if the spirits that at such times only could be evoked by him from the Aidenn, close by whose portals his disturbed soul sought to forget the ills to which his constitution subjected him―close by the Aidenn where were those he loved―the Aidenn which he might never see, but in fitful glimpses, as its gates opened to receive the less fiery and more happy natures whose destiny to sin did not involve the doom of death. (彼はいつも夢見るひとだった――想像の領域に住んでいた――天国にせよ地獄にせよ――一緒にいたのは自分の脳髄がこしらえた創造物と出来事だった。彼が道を歩くときは、狂気に駆られているか憂鬱に落ちているのか、その唇は不分明な呪詛を吐いてうごめき、うわむきの目が何を情熱的に祈っているのかといえば(自分自身のためでは決してなく、というのも彼は既に地獄落ちの宿命にあると感じていたか感じていると公言していたからで)自分がそのときに崇拝していた偶像たちの幸福のためであった。あるいはまた彼の視線は苦悩でさいなまれる心に内向化され、憂鬱の経帷子に顔を包んだまま、彼は、いかなる激しい嵐にも向かっていった。そして一晩じゅう、びしょ濡れの衣服をまとい両手で風雨を振り払って、こうした時に彼によってあエイデン〔天国〕から呼び出されたとしか思われぬ霊たちにむかってであるかのように話すのだった。天国の扉の近くで、彼の悩める魂はその体が自分を従えさせる悪を忘れようと試みた――彼の愛する者たちがいたエイデンの近くで――彼自身は発作的な一瞥によって以外は垣間見ることの決してかなわない天国であった。なぜなら天国の門が開かれて迎え入れるのはそれほど火のような激情に駆られぬ、もっと幸せな性質のひとびとであって、彼らの罪に対する宿命は死の運命を含んではいなかったからである。)

“He seemed, except when some fitful pursuit subjugated his will and engrossed his faculties, always to bear the memory of some controlling sorrow. The remarkable poem of ‘The Raven’ was probably much more nearly than has been supposed, even by those who were very intimate with him, a reflection and an echo of his own history. He was that bird’s

“ ‘unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore―

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never-never more.’

“Every genuine author in a greater or less degree leaves in his works, whatever their design, traces of his personal character: elements of his immortal being, in which the individual survives the person. While we read the pages of the ‘Fall of the House of Usher,’ or of ‘Mesmeric Revelations,’ we see in the solemn and stately gloom which invests one, and in the subtle metaphysical analysis of both, indications of the idiosyncrasies of what was most remarkable and peculiar in the author’s intellectual nature. But we see here only the better phases of his nature, only the symbols of his juster action, for his harsh experience had deprived him of all faith in man or woman. He had made up his mind upon the numberless complexities of the social world, and the whole system with him was an imposture. This conviction gave a direction to his shrewd and naturally unamiable character. Still, though he regarded society as composed altogether of villains, the sharpness of his intellect was not of that kind which enabled him to cope with villany, while it continually caused him by overshots to fail of the success of honesty. He was in many respects like Francis Vivian in Bulwer’s novel of ‘The Caxtons.’ Passion, in him, comprehended -many of the worst emotions which militate against human happiness. You could not contradict him, but you raised quick choler; you could not speak of wealth, but his cheek paled with gnawing envy. The astonishing natural advantages of this poor boy―his beauty, his readiness, the daring spirit that breathed around him like a fiery atmosphere―had raised his constitutional self-confidence into an arrogance that turned his very claims to admiration into prejudices against him. Irascible, envious―bad enough, but not the worst, for these salient angles were all varnished over with a cold, repellant cynicism, his passions vented themselves in sneers. There seemed to him no moral susceptibility; and, what was more remarkable in a proud nature, little or nothing of the true point of honor. He had, to a morbid excess, that, desire to rise which is vulgarly called ambition, but no wish for the esteem or the love of his species; only the hard wish to succeed-not shine, not serve -succeed, that he might have the right to despise a world which galled his self-conceit.

“We have suggested the influence of his aims and vicissitudes upon his literature. It was more conspicuous in his later than in his earlier writings. Nearly all that he wrote in the last two or three years-including much of his best poetry-was in some sense biographical; in draperies of his imagination, those who had taken the trouble to trace his steps, could perceive, but slightly concealed, the figure of himself.”

Apropos of the disparaging portion of the above well-written sketch, let us truthfully say:―

Some four or five years since, when editing a daily paper in this city, Mr. Poe was employed by us, for several months, as critic and sub-editor. This was our first personal acquaintance with him. He resided with his wife and mother at Fordham, a few miles out of town, but was at his desk in the office, from nine in the morning till the evening paper went to press. With the highest admiration for his genius, and a willingness to let it atone for more than ordinary irregularity, we were led by common report to expect a very capricious attention to his duties, and occasionally a scene of violence and difficulty. Time went on, however, and he was invariably punctual and industrious. With his pale, beautiful, and intellectual face, as a reminder of what genius was in him, it was impossible, of course, not to treat him always with deferential courtesy, and, to our occasional request that he would not probe too deep in a criticism, or that he would erase a passage colored too highly with his resentments against society and mankind, he readily and courteously assented-far more yielding than most men, we thought, on points so excusably sensitive. With a prospect of taking the lead in another periodical, he, at last, voluntarily gave up his employment with us, and, through all this considerable period, we had seen but one presentment of the man-a quiet, patient, industrious, and most gentlemanly person, commanding the utmost respect and good feeling by his unvarying deportment and ability.

Residing as he did in the country, we never met Mr. Poe in hours of leisure; but he frequently called on us afterward at our place of business, and we met him often in the street-invariably the same sad mannered, winning and refined gentleman, such as we had always known him. It was by rumor only, up to the day of his death, that we knew of any other development of manner or character. We heard, from one who knew him well (what should be stated in all mention of his lamentable irregularities), that, with a single glass of wine, his whole nature was reversed, the demon became uppermost, and, though none of the usual signs of intoxication were visible, his will was palpably insane. Possessing his reasoning faculties in excited activity, at such times, and seeking his acquaintances with his wonted look and memory, he easily seemed personating only another phase of his natural character, and was accused, accordingly, of insulting arrogance and bad-heartedness. In this reversed character, we repeat, it was never our chance to see him. We know it from hearsay, and we mention it in connection with this sad infirmity of physical constitution; which puts it upon very nearly the ground of a temporary and almost irresponsible insanity.

The arrogance, vanity, and depravity of heart, of which Mr. Poe was generally accused, seem to us referable altogether to this reversed phase of his character. Under that degree of intoxication which only acted upon him by demonizing his sense of truth and right, he doubtless said and did much that was wholly irreconcilable with his better nature; but, when himself, and as we knew him only, his modesty and unaffected humility, as to his own deservings, were a constant charm to his character. His letters, of which the constant application for autographs has taken from us, we are sorry to confess, the greater portion, exhibited this quality very strongly.

In one of the carelessly written notes of which we chance still to retain possession, for instance, he speaks of “The Raven”―that extraordinary poem which electrified the world of imaginative readers, and has become the type of a school of poetry of its own―and, in evident earnest, attributes its success to the few words of commendation with which we had prefaced it in this paper. ―It will throw light on his sane character to give a literal copy of the note:―

“FORDHAM, April 20, 1849.“My dear Willis:―The poem which I inclose, and which I am so vain asto hope you will like, in some respects, has been just published in apaper for which sheer necessity compels me to write, now and then. It pays well as times go-but unquestionably it ought to pay ten prices;for whatever I send it I feel I am consigning to the tomb of theCapulets. The verses accompanying this, may I beg you to take out ofthe tomb, and bring them to light in the ‘Home journal?’ If you can oblige me so far as to copy them, I do not think it will be necessaryto say ‘From the――, ―that would be too bad;―and, perhaps, ‘From a late――paper,’ would do.

“I have not forgotten how a ‘good word in season’ from you made ‘TheRaven,’ and made ‘Ulalume’ (which by-the-way, people have done me thehonor of attributing to you), therefore, I would ask you (if I dared)to say something of these lines if they please you.

“Truly yours ever,

“EDGAR A. POE.”

In double proof of his earnest disposition to do the best for himself, and of the trustful and grateful nature which has been denied him, we give another of the only three of his notes which we chance to retain:―“FORDHAM, January 22, 1848.

“My dear Mr. Willis:―I am about to make an effort at re-establishingmyself in the literary world, and feel that I may depend upon youraid.

“My general aim is to start a Magazine, to be called ‘The Stylus;’ but it would be useless to me, even when established, if not entirelyout of the control of a publisher. I mean, therefore, to get up ajournal which shall be my own at all points. With this end in view, I must get a list of at least five hundred subscribers to begin with;nearly two hundred I have already. I propose, however, to go Southand West, among my personal and literary friends―old college andWest Point acquaintances―and see what I can do. In order to get themeans of taking the first step, I propose to lecture at the Society Library, on Thursday, the 3d of February, and, that there may be nocause of squabbling, my subject shall not be literary at all. I have chosen a broad text―‘The Universe.’

“Having thus given you the facts of the case, I leave all the restto the suggestions of your own tact and generosity. Gratefully, mostgratefully,

“Your friend always,

“EDGAR A. POE.”

Brief and chance-taken as these letters are, we think they sufficiently prove the existence of the very qualities denied to Mr. Poe―humility, willingness to persevere, belief in another’s friendship, and capability of cordial and grateful friendship! Such he assuredly was when sane. Such only he has invariably seemed to us, in all we have happened personally to know of him, through a friendship of five or six years. And so much easier is it to believe what we have seen and known, than what we hear of only, that we remember him but with admiration and respect―these descriptions of him, when morally insane, seeming to us like portraits, painted in sickness, of a man we have only known in health.

But there is another, more touching, and far more forcible evidence that there was goodness in Edgar A. Poe. To reveal it we are obliged to venture upon the lifting of the veil which sacredly covers grief and refinement in poverty; but we think it may be excused, if so we can brighten the memory of the poet, even were there not a more needed and immediate service which it may render to the nearest link broken by his death.

Our first knowledge of Mr. Poe’s removal to this city was by a call which we received from a lady who introduced herself to us as the mother of his wife. She was in search of employment for him, and she excused her errand by mentioning that he was ill, that her daughter was a confirmed invalid, and that their circumstances were such as compelled her taking it upon herself. The countenance of this lady, made beautiful and saintly with an evidently complete giving up of her life to privation and sorrowful tenderness, her gentle and mournful voice urging its plea, her long-forgotten but habitually and unconsciously refined manners, and her appealing and yet appreciative mention of the claims and abilities of her son, disclosed at once the presence of one of those angels upon earth that women in adversity can be. It was a hard fate that she was watching over. Mr. Poe wrote with fastidious difficulty, and in a style too much above the popular level to be well paid. He was always in pecuniary difficulty, and, with his sick wife, frequently in want of the merest necessaries of life. Winter after winter, for years, the most touching sight to us, in this whole city, has been that tireless minister to genius, thinly and insufficiently clad, going from office to office with a poem, or an article on some literary subject, to sell, sometimes simply pleading in a broken voice that he was ill, and begging for him, mentioning nothing but that “he was ill,” whatever might be the reason for his writing nothing, and never, amid all her tears and recitals of distress, suffering one syllable to escape her lips that could convey a doubt of him, or a complaint, or a lessening of pride in his genius and good intentions. Her daughter died a year and a half since, but she did not desert him. She continued his ministering angel―living with him, caring for him, guarding him against exposure, and when he was carried away by temptation, amid grief and the loneliness of feelings unreplied to, and awoke from his self abandonment prostrated in destitution and suffering, begging for him still. If woman’s devotion, born with a first love, and fed with human passion, hallow its object, as it is allowed to do, what does not a devotion like this-pure, disinterested and holy as the watch of an invisible spirit―say for him who inspired it?

We have a letter before us, written by this lady, Mrs. Clemm, on the morning in which she heard of the death of this object of her untiring care. It is merely a request that we would call upon her, but we will copy a few of its words―sacred as its privacy is―to warrant the truth of the picture we have drawn above, and add force to the appeal we wish to make for her:

“I have this morning heard of the death of my darling Eddie. . . . Can you give me any circumstances or particulars? . . . Oh! do not desert your poor friend in his bitter affliction! . . . Ask Mr. ――to come, as I must deliver a message to him from my poor Eddie. . . .

I need not ask you to notice his death and to speak well of him. I know you will. But say what an affectionate son he was to me, his poor desolate mother. . . .”

To hedge round a grave with respect, what choice is there, between the relinquished wealth and honors of the world, and the story of such a woman’s unrewarded devotion! Risking what we do, in delicacy, by making it public, we feel―other reasons aside―that it betters the world to make known that there are such ministrations to its erring and gifted. What we have said will speak to some hearts. There are those who will be glad to know how the lamp, whose light of poetry has beamed on their far-away recognition, was watched over with care and pain, that they may send to her, who is more darkened than they by its extinction, some token of their sympathy. She is destitute and alone. If any, far or near, will send to us what may aid and cheer her through the remainder of her life, we will joyfully place it in her bands.

茶色にした部分、何を言っているのかわからないけれど有名なグリズウォルドの人格攻撃の一節を訳したら疲れて力尽きました。とりあえずウィリスのテクストの細かいパンクチュエーション等は今年出た次の本におおむね従いました (pp. 94-99)(ただしグリズウォルドの引用は "Tribune [excerpts from the Ludwig obtuary follow]." というふうに省略されているので、他 (pp. 73-80 に収録の “"Death of Edgar Allan Poe" in New York Daily Tribune (1849) / "Ludwig" [Rufus Wilmot Griswold]”)から補いました)。――

Benjamin F. Fisher, ed. Poe in His Own Time: A Biographical Chronicle of His Life, Drawn from Recollections, Interviews, and Memoirs by Family, Friends, and Associates. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2010. 312pp.

オシャレ番長 Fashion Gang Leader [断章 Fragments]

女性作家の言祝ぎ A Celebration of Women Writers [作家の肖像]

「女性作家の言祝ぎ」と訳すのが適当かどうかはわかりませんが、A Celebration of Women Writers はペンシルヴェニア大学のメアリー・マーク・オッカーブルームさんが創った電子図書館で、あらゆる時代の女性の書き物を包括的に所蔵することをめざしています。著作権の切れた過去の著者のEテクストが無料で利用できます。(現在活躍する女性作家へのリンクもありますけど。)名前、国、人種、時代によって、ブラウズしたり検索したりできます。とくにマイナーな女性作家の作品はしばしば埋もれたり散逸したり無視されたりしがちだと思うのですが、この同じ一つの場所にみんな集まっていて、深みと広がりと多様性をもつサイト(=光景)は感動的で印象深い。

A Celebration of Women Writers, edited by Mary Mark Ockerbloom at University of Pennsylvania, is a comprehensive digital library of women’s writing throughout history. E-texts of the past authors, copyright expired, are freely available. (It has also links to contemporary women authors.) You can browse or search by name, country, ethnicity, or time. Minor women writers’ works are often buried and lost or dismissed; here they are gathered into one place, and the sight and the site is exciting and impressive with the depth and breadth and variety.

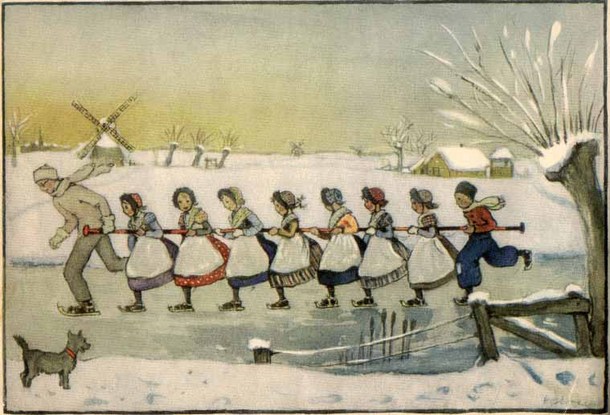

Hilda Van Stockum, A Day on Skates: The Story of a Dutch Picnic (New York: Harper, 1934), frontispiece [illustrated by the author]. <http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/stockum/skates/skates.html>

////////////////////////

A Celebration of Women Writers <http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/>

アメリカにいたころジーン・ウェブスターの著作のE-texts を調べていて行き当たっていたのでした(『カリフォルニア時間』2008.6.30 の「June 30 Pg4のミステリー――本の電子化について――The Four-Pools Mystery by Jean Webster (2)」。独自のE-texts と他のサイトのE-texts へのリンクを含んでいます。その、他のサイトで女性作家に集中しているものとして――

Emory Women Writers Resource Project <http://womenwriters.library.emory.edu/ewwrp/> [Emory]

Victorian Women Writers Project <http://webapp1.dlib.indiana.edu/vwwp/welcome.do> [Indiana]

19th Century American Women Writers <http://www.lehigh.edu/~dek7/SSAWW/eTextLib.htm> 〔Society for the Study of American Women Writers〕

Digital Schomburg African American Women Writers of the 19th Century <http://digital.nypl.org/schomburg/writers_aa19/toc.html> 〔New York Public Library〕

イニシアル(イニシャル) (1) Initials [モノ things]

BGM はやまがたすみこどす♪。

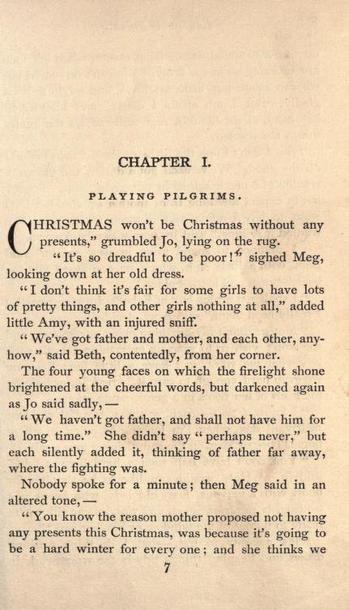

『若草物語』の各章の冒頭は、発話のことが多い。ノートン版を見ていたら、引用符が付いていないことにカチンときた。で、コンピューターの印刷の問題なのではないか、とか適当なことをひとに言ったのだけれど、初版を見たら、始まりの “ (ダブル・クオーテーション・マーク)がもとから抜けていた。――

"Christmas won't be Christmas without any presents," grumbled Jo, lying on the rug.

"Jo! Jo! where are you?" cried Meg, at the foot of the garret stairs.

しかし・・・・・・この章の冒頭のデカイ文字はイニシアルというやつで、印刷屋、あるいはデザイナーによっては引用符を付せられない、あるいは付さないということであって、それを普通の活字(活字じゃなくてコンピューター写植でしょうけど)に組み直したときに引用符を補わないのはバカでしょう。

20世紀初めのリプリント版は、当然引用符を補っています。――

-ceff4.jpg)

Orchard House Edition (Boston: Little Brown, 1915) <http://www.archive.org/details/littlewomenormeg00alcouoft>――この挿絵は Jessie Wilcox Smith です。

19世紀末近くに Frank T. Merrill による200枚超の挿絵を付して出された合冊の regular edition (Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1880)も当然引用符を補っています。――

<http://www.archive.org/details/littlewomenorme00alcogoog>

グーテンベルグのE-text だって、当然引用符を補っています。――

ノートン版の1章、3章、4章、5章、7章、8章、9章、11章、15章はみんな冒頭の引用符を落としています。編者たちは1868年の初版を忠実に示そうとしたのでしょうか。しかし、異同と考えていないらしいのは、381から385ページの "A Note on the Text" そして、386ページから408ページまでにおよぶ詳しい "Textual Variants" (『若草物語』第二部も含む)という、1868-69年の初版と1880-1881 年の regular edition の異同リストに、この引用符の脱落を示していないことからうかがえます。

イニシアルを飾り文字にするとか(初版のようにシンプルに)大きな字にするとかしていたなら許容されるかもしれないけれど、普通の字体にしておいて引用符を置かないのは無知か不注意との誤解を受けかなねないと思うのですけれど。

William Morris の Kelmscott Press 私家印刷本

///////////////////////////////////

"Initial" - Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Initial> 〔もっぱら本におけるデザインを扱っており――"In a written or published work, an initial is a letter at the beginning of a work, a chapter, or a paragraph that is larger than the rest of the text. The word is derived from the Latin initialis, which means standing at the beginning. An initial often is several lines in height and in older books or manuscripts, sometimes ornately decorated. (書物の中でイニシアルというのは著作、章、あるいはパラグラフの始まりに置かれる文字で、他のテクストの部分よりも大きなものをいう。この語はラテン語の「始まりに立つ」を意味する initialis に由来する。イニシアルはしばしば数行分の高さがあり、古い本や手稿ではときに美術的に装飾されている。)〕

「イニシャル」 - Wikipedia <http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%A4%E3%83%8B%E3%82%B7%E3%83%A3%E3%83%AB> 〔なぜかもっぱら名前のイニシャルを扱っており〕

1024.jpg)

.jpg)