ポーが書評した本 (26) チャールズ・ホフマンの『西部の一冬』 (1835) Books Reviewed by Poe (26): _A Winter in the West_ by a New-Yorker [Charles Fenno Hoffman] [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

続いて、ポーの最初期の批評(と想定されている文章)の中から、順番でいうと、雑誌紹介2篇に続く『サミュエル・ドル―伝』のつぎの『ナポレオン伝』のつぎの『万国著名裁判』のつぎの『ノー・フィクション――最近の興味深い事実に基づいた物語』 のつぎの『万国著名女性回顧録』のつぎの『感化力――道徳物語』のつぎの『英国海賊、追剥、盗賊伝』のつぎの『詩人の告白』のつぎの『花言葉』のつぎの『実践的教育』のつぎの『ハイランドの密輸人』のつぎの『ウァレリウス』 のつぎの『北へ東へカーネル・クロケットの旅の記』のつぎの『イロラー・デ・コーシー』のつぎの記事(『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』誌1835年4月号 "Critical Notices" 459ページ)。

[Charles Fenno Hoffman]. A Winter in the West. By a New-Yorker. 2 vols. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1835.

〔チャールズ・フェンノ・ホフマン著〕 『西部の冬』 「或るニューヨーカー」著 ニューヨーク: ハーパー&ブラザーズ、1835年

チャールズ・フェンノ・ホフマン Charles Fenno Hoffman, 1806-84 は、ニューヨーク州の検事総長を勤めたJosiah Ogden Hoffmanの息子で、母親も政治家の家系で、要するに名家の都会っ子なのだけれど、12歳のときにボートの事故で脚を失ない、義足となりました。ニューヨーク大、コロンビア大を出て法曹界に入るが、法律の仕事は少ししかせず、詩を書き、やがて1833年Knickerbocker Magazineを創刊し、編集者・詩人・小説家としてニューヨーク市の文壇・ジャーナリズムで活躍するようになりました。アーヴィングやクーパーやブライアントらの作家がかかわる『ニッカーボッカー・マガジン』の編集に携わったのは創刊号からの3号のみで、Lewis Gaylord Clark (1808-73) に編集を譲りますけど、そのクラークというのは後年1840年代にポーの文学的仇敵のひとりとなります。ホフマンの詩はグリズウォルドが高く評価するところとなり、そのことに対してポーは連載エッセイ「ニューヨーク市の文人たち The Literati of New York City」(1846) で反発したり、クラークについてもこきおろしたりしますけれど、それはあとのこと。さらにクラークは狂気を発して晩年の30年余を精神病院で暮らしますけれど、それは1849年秋、ポーが亡くなる年のこと。『西部の冬』はクラークが初めて出した匿名の本で、紀行文としてポーはたんたんと短評を書いています。西部と言っても、ミズーリ州セントルイスまでです。インディアンへの言及の多さについての言及と、博愛主義(人道主義)的関心についての関心が、ポーの文章で目を引きます。

Charles Fenno Hoffman (1834)

image via The American Literary Blog, February 7, 2012 <http://americanliteraryblog.blogspot.jp/2012/02/birth-of-hoffman-takes-away-hope-from.html>

Vol. 1 337pp. <http://www.archive.org/stream/winterinwest01hoff#page/n5/mode/2up>

Vol. 2 346pp. <http://www.archive.org/stream/winterinwestho02hoff#page/n5/mode/2up>

もっとも、匿名といっても、現在のコピーライト記載のページには、Charles F. Hoffman という本名が記されています。そしてポーも書評の最後のところではホフマン氏の月刊誌編集について触れています――

ポーの書評――

A Winter in the West, by a New Yorker. New York, Harper and Brothers. This is a work of great sprightliness, and is replete with instruction and amusement. The writer evinces much talent in producing an interesting narrative of a journey performed in the most unpropitious period of the year. His observations on life in the backwoods are sensible, and we should imagine correct, and his details in relation to Michigan particularly interest us. The adventures of the road are told with great vivacity, and although there are no thrilling scenes or surprising incidents in the book, it cannot be read with indifference. The traits of Indian character scattered through its pages are vivid and striking, and the reflections on the condition of that fast falling race mark the philanthropic spirit of the author. Mr. Hoffman, formerly connected with the New York American, and now Editor of a Monthly Magazine, is the reputed author of this sprited work. [Southern Literary Messenger, April 1835, 459]

ポーが書評した本 (27) ジェレマイア・レノルズの『米国フリゲート艦ポトマック号の航海』 (1835) Books Reviewed by Poe (27): _Voyage of the U.S. Frigate Potomac_ by J. N. Reynolds [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

ポーは、いろんな本の書評を書きました。文学書だけじゃなくていろんな本の書評を書き、いろんな本のなかには、自身の作品の「ソース source」になったものも、当然のことながら、あります。

ポーの長篇小説『アーサー・ゴードン・ピム』(1837-38) のソースとして、第16章の本文中でポー自身が言及しているのが Benjamin Morrell, Narrative of Four Voyages to the South Seas and Pacific, 1822-1831 (1832) と J. N. Reynolds, Address on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas (1836) ですけれど、レノルズについてはこのパンフレットも含めて3冊の著作の書評を書いており、いずれの本も『ピム』に影響が認められます。

(1) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Voyage of the Potomac (1835): reviewed in the June 1835 SLM [Southernn Literary Messenger].

(2) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs (1836): reviewed in the August 1836 SLM.

(3) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Address on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas (1836): reviewed in the January 1837 SLM.

で、最初の本の書評については、Collected Works of Edgar Allan Poe の編者のBurton Pollin は Pym を入れた Imaginary Voyages の巻の解説では、1835年の、まだポーが正式に編集者として雇われる前のものだし、ポーのものじゃないんじゃないか、と書いてるのだけれど、そんなこと言ったらこのシリーズの (26)までとりあげてきた1835年4月号のSLM の書評はみな不確かで、ワヤになってしまうのと、あとは学者の研究によって、上記 (1) の本から数百語を超える「引用」が見つかっているので、ポーが読んでいるのは確かです(そしてポーリン自身が同じCollected Works の、のちの、 SLM の書評の巻の編者としては、この書評をポーに帰しています)。なお、モレルやレノルズの本だけが『ピム』の航海関係の資料というわけではなくて、30冊を超える本が資料として挙がってもいます。けど、極地への航海(かつ地球空洞説とのかかわり)というところで、レノルズは大きな源泉なわけです。

ジェレマイア・N・レノルズ(1799-1858) は、アメリカの航海者・探検家・講演家で、南氷洋への国家的探検航海を唱導したひとですが、「シムズの穴」で有名な John Cleves Symmes, Jr. の地球空洞説に共鳴し、一緒に講演ツアーをしたりします。そこんところで、極点で海水は地下に落ち込んでアビシニアあたりで出てくるとか、17世紀のアタナシウス・キルヒャーにつながったり、ポー的には極北=極南=書くことの始源みたいなイメジとつながっていく。ウィキペディアは、いっぽうで、レノルズの、伝説の白鯨についての著作 Mocha Dick (1839) がメルヴィルの『白鯨(モービー・ディック)』に与えた影響を書いているけれど、文化人類学者ミルチャ・エリアーデのことばでいう「中心のシンボリズム」のポーとメルヴィルのふたりの作家が関わっていたことは明らかだと思いますねん。"Rememiah N. Reynolds" @Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeremiah_N._Reynolds>

Voyage of the United States Frigate Potomac, Under the Command of Commodore John Downes, during the Circumnavigation of the Globe, in the Years 1831, 1832, 1833, and 1834; Including a Particular Account of the Engamement at Quallah-Battoo, on the Coast of Sumatra; with All the Official Documents Relating to the Same. By J. N. Reynolds. Illustrated by Several Engravings. New-York: Harper and Brothers, 1835. 560pp.

E-text <http://archive.org/stream/voyageunitedsta00reyngoog#page/n4/mode/2up> ……これはunknown library からのE-bookなのだけれど、10倍近くダウンロードのあるOxford大学図書館蔵のもの <http://archive.org/details/voyageunitedsta01reyngoog> は Appendix の図表が空白になっていて(少なくとも Read Onlineでは)、こっちのほうがよいかと。

Voyage of the U. S. Frigate Potomac, under the command of Commodore John Downes, during the circumnavigation of the globe in the years 1831-32-33 and 34: including a particular account of the engamement at Quallah-Battoo, on the Coast of Sumatra. By J. N. Reynolds. This is a thick volume of nearly 600 pages, well printed, upon good paper, with some excellent engravings, and published by the Harpers. Mr. Reynolds, the author, or to speak more correctly, the compiler, will be remembered as the associate of Symmes in his remarkable theory of the earth, and a public defender of that very indefensible subject, upon which he delivered a series of lectures in many of our principal cities. With the exception, however, of seven chapters, the matter forming the work now published is gleaned from the ship's journal, from the private journals of the officers, and from papers furnished by Commodore Downes himself. This fact will speak much for the authenticity of th details, and very valuable information scattered through the book. Mr. R. himself was not with the Potomac during the circumnavigation, having joined her in 1832 at Valparaiso. Our readers are, of course, acquainted with the object of the Potomac's voyage, and with the outrage perpetrated by the Malays on the ship Friendship in 1831, which rendered it an indispensable duty onthe part of our government to demand an indemnity. The result of this demand, and the actionad Quallah-Battoo are graphically sketched by Mr. Reynolds. Every body will be pleased, too, with his description of Canton and of Lima. He writes well, although somewhat too enthusiastically, and his book will gain him reputation as a man of science and accurate observation. It will form a valuable addition to our geographical libraries. Southern Literary Messenger, June 1835: 594-95.

//////////////////////////////////

Daniel J. Tynan, “J. N. Reynold’s Voyage of the Potomac: Another Source for The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym,” Poe Studies, December 1971, vol. IV, no. 2, 4:35-37 @Edgar Allan Poe Society <http://www.eapoe.org/pstudies/ps1970/p1971207.htm>

David Standish, Hollow Earth: The Long and Curious History of Imagining Strange Lands, Fantastical Creatures, Advanced Civilizations, and Marvelous Machines Below the Earth's Surface (Da Capo Press, 2007). <http://books.google.com.eg/books?id=0z-jUbHGyzoC&pg=PA101&lpg=PA101&dq=Poe+Voyage+of+Potomac&source=bl&ots=eDCldJCVXv&sig=F7bNNC0QeLultnh-V5ehLEQ5PlI&sa=X&ei=t_41UJyRMe_4mAWxw4HICA&ved=0CCwQ6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=Poe%20Voyage%20of%20Potomac&f=false>

ポーが書評した本 (28) ジェレマイア・レノルズの『海事委員会報告』 (1836) Books Reviewed by Poe (28): _Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs_ by J. N. Reynolds [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs, to whom was referred memorials from sundry citizens of Connecticut interested in the whale fishing, praying that an exploring expedition be fitted out to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas. Senate Document No. 262, 24th COngress, 1st session; Vol. 3. 88pp. Washington, D. C., 1836.

ポーの長篇小説『アーサー・ゴードン・ピム』(1837-38) のソースとして、第16章の本文中でポー自身が言及しているのが Benjamin Morrell, Narrative of Four Voyages to the South Seas and Pacific, 1822-1831 (1832) と J. N. Reynolds, Address on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas (1836) ですけれど、レノルズについてはこのパンフレットも含めて3冊の著作の書評を書いており、いずれの本も『ピム』に影響が認められます。

(1) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Voyage of the Potomac (1835): reviewed in the June 1835 SLM [Southernn Literary Messenger].

(2) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs (1836): reviewed in the August 1836 SLM.

(3) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Address on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas (1836): reviewed in the January 1837 SLM.

で、ふたつめの本はInternet Archive に見つかりませんでした。あるのは1817年から1870年代までの "Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs なんたらかんたら" という題の報告書が十数冊。

どうやら議会の報告書みたいなものであって、「本」というのではないみたい。アメリカ議会図書館 Library of Congress を探ると出てくるかもしれない。

いまは、しかし、"South-Sea Expedition" と銘打った長めの書評ですので、そちらの書き取りをメインに。

SOUTH-SEA EXPEDITION.

Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs, to whom was referred memorials from sundry citizens of Connecticut interested in the whale fishing, praying that an exploring expedition be fitted out to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas. March 21, 1836.

That a more accurate, defined, and available knowledge than we at present possess, of the waters, islands, and continental coasts of the great Pacific and Southern Oceans, has long been desirable, no unprejudiced individual conversant with the subject, is likely to deny. A portion of the community unrivalled in activity, enterprise and perseverance, and of paramount importance both in a political and commercial point of view, has long been reaping a rich harvest of individual wealth and national honor in these vast regions. The Pacific may be termed the training ground, the gymnasium of our national navy. The hardihood and daring of that branch of our commercial marine employed in its trade and fisheries, have almost become a proverb. It is in this class we meet with the largest aggregate of that cool self-possession, courage, and enduring fortitude, which have won for us our enviable position among the great maritime powers; and it is fi-om this class we may expect to recruit a considerable proportion of the physical strength and moral intelligence necessary to maintain and improve it. The documentary evidence upon which the report before us is based, forms an appendix to it, and is highly interesting in its character. It awakens our admiration at the energy and industry which have sustained a body of daring men, while pursuing a dangerous and arduous occupation, amid the perils and casualties of an intricate navigation, in seas imperfectly known. It enlists our sympathies in the hardships and difficulties they have combatted, places in strong relief the justice of their claims upon the nation for aid and protection, and shows the expediency of the measure which has at last resulted from their representations. The report itself is clear, manly, decided — the energetic language of men who, having examined the data submitted to them with the consideration the interests it involved seem to require, are anxious to express their sentiments with a force and earnestness suited to their views of the urgent occasion and of the course they recommend.

It is a glorious study to contemplate the progress made by human industry, from stage to stage, when engaged in the prosecution of a laudable object. Little more than a century ago, only the crews of a few miserable open boats, too frail to venture far from land, waged a precarious warfere with the great leviathans of the deep, along the shores of Cape Cod and Nantucket — then occupied, at distant intervals by a few inconsiderable fishing stations. The returns even of these first efforts were lucrative, and more appropriate vessels for the service were fitted out. These extended their cruises northward to Labrador, and southward to the West Indies. At length the adventurers, in vessels of yet greater capacity, strength and durability, crossed die Equator and followed their hardy calling along the Eastern Shore of the Southern Peninsula and on the Western and North Western coast of Africa. The Revolution of course operated as a temporary check to their prosperity, but shordy thereafter these daundess mariners doubled Cape Horn, and launched their daring keels into the comparatively unknown waste beyond, in search of their gigantic prey. Since that fortunate advent, the increase in the shipping, extent, and profits of the fishery, has been unprecedented, and new sources of wealth the importance of which it is at present impossible to estimate, have been opened to us in the same quarter. The trade in skins of the sea-otter and seal, in the fur of land animals on the North West coast, &c. has been extensive in extent and avails. The last mentioned animal, besides the valuable ivory it affords, yields a coarse oil which, in the event of the whale becoming extinct before the perpetual warfare of man, would prove a valuable article of consumption. Of the magnitude of the commercial interest involved in different ways in the Pacific trade, an idea may be gathered in the following extract jfrom the main subject of our review. Let it be borne in mind, that many of the branches of this trade are as yet in their infancy, that the natural resources to which they refer are apparendy almost inexhaustible; and we shall become aware that all which is now in operation, is but as a dim shadow to the mighty results which may be looked for, when this vast field for national enterprise is better known and appreciated.

"No part of the commerce of this country is more important than that carried on in the Pacific Ocean. It is a large in amount. Not less than $12,000,000 are invested in and actively employed by one branch of the whale fishery alone; in the whole trade there is directly and indirectly involved not less than fifty to seventy millions of property. In like manner from 170 to 200,000 tons of our shipping, and from 9 to 12000 of our seamen are employed, amounting to about one-tenth of the whole navigation of the Union. Its results are profitable. It is to a great extent not a mere exchange of commodties, but the creation of wealth by labor from the ocean. The fisheries alone produce at this time an anual income of from five to six millions of dollars; and it is not possible to look at Nantucket, New Bedford, New London, Sag Harbor and a large number of other districts upon our Northern coasts, without the deep conviction that it is an employment alike beneficial to the moral, political, and commercial interests of our fellow-citiziens."

In a letter from Commodore Downes to the Honorable John Reed, which forms part of the supplement to the report, that experienced officer observes ―

"During the circumnavigation of the globe, in which I crossed the equator six times, and varied my course from 40 deg. North to 57 deg. South latitude, I have never found myself beyond the limits of our commercial marine. The accounts given of the dangers and losses to which our ships are exposed by the extension of our trade into seas but little known, so far, in my opinion from being exaggerated, would admit of being placed in bolder relief, and the protection of government employed in stronger terms. I speak from practical knowledge, having myself seen the dangers and painfully felt the want of the very kind of information which our commercial interests so much need, and which, I suppose, would be the object of such an expedition as is now under consideration before the committee of Congress to give. * * * * * * *

The commerce of our country has extended itself to remote parts of the world, is carried on around islands and reefs not laid down in the charts, among even groups of islands from ten to sixty in number, abounding in objects valuable in commerce, but of which nothing is known accurately; no not even the sketch of a harbor has been made, while of such as are inhabited our knowledge is still more imperfect."

In reading this evidence (derived from the personal observation of a judicious and experienced commander) of the vast range of our commerce in the regions alluded to, and of the imminent risks and perils to which those engaged in it are subjected, it cannot but create a feeling of surprise, that a matter of such vital importance as the adoption of means for their relief, should so long have been held in abeyance. A tabular view of the discoveries of our whaling captains in the Pacific and Southern seas, which forms part of another document, seems still further to prove the inaccuracy and almost utter worthlessness of the charts of these waters, now in use.

Enlightened liberality is the truest economy. It would not be difficult to show, that even as a matter of pecuniary policy the efficient measures at length in progress to remedy the evils complained of by this portion of our civil marine, are wise and expedient. But let us take higher ground. They were called for — Firstly: as a matter of public justice. Mr. Reynolds, in his comprehensive and able letter to the chairman of the committee on Naval Affairs, dated 1828, which, with many other conclusive arguments, and fiicts furnished by that gendeman, forms the nudn evidence on which the late committee founded their report — observes, with reference to the Pacific;

"To look after our merchant there — to offer him every possible facility — to open new channels for his enterprise, and to keep up a respectable naval force to protect him — is only paying a debt we owe to the commerce of the country: for millions have flowed into the treasury from this source, before one cent was extended for its protection."

So far, then, we have done little as a nation to fiicilitate, or increase, the operations of our commerce in the quarter indicated; we have left the advenmrous merchant and the hardy fisherman, to fight their way among reefs of dangerous rocks, and through the channels of undescribed Archipelagos, almost without any other guides than their own prudence and sagacity; but we have not hesitated to partake of the firuits of their unassisted toils, to appropriate to ourselves the credit, respect and consideration their enterprise has commanded, and to look to their clasa as the strongest support of that main prop of our national power, — a hardy, effective, and well disciplined national navy.

Secondly. Our pride as a vigorous commercial empire, should stimulate us to become our own pioneers in that vast island-studded ocean, destined, it may be, to become, not only the chief theatre of our traffic, but the arena of our fiiture naval conflicts. Who can say, viewing the present rapid growth of our population, that the Rocky Mountains shall forever constitute the western boundary of our republic, or that it shall not stretch its dominion from sea to sea. This may not be desirable, but signs of the times render it an event by no means without the pale of possibility.

The intercourse carried on between the Pacific islands and the coast of China, is highly profitable, the immense rcttdrns of the whale fishery in the ocean which surrounds those islands and along the continental coasts have been already shown. Our whalers have traversed the wide expanse from Peru and Chili on the west, to the isles of Japan on the east, gathering nadonal reverence as well as mdividual emolument, in their course; and yet until the late appropriation. Congress has never yielded them any pecuniary assistance, leaving their security to the scientific labors of countries far more distant, and infinitely less interested, than our own.

Thirdly. It is our duty, holding as we do a high rank in the scale of nations, to contribute a large share to that aggregate of useful knowledge, which is the common property of all. We have astronomers, mathematicians, geologists, botanists, eminent professors in every branch of physical science — we are unincumbered by the oppression of a national debt, and are free from many other drawbacks which fetter and control the measures of the trans-Atlantic governments. We possess, as a people, the mental elasticity which liberal institutions inspire, and a treasury which can afford to remunerate scientific research. Ought we not, therefore, to be foremost in the race of philanthropic discovery, in every department embraced by this comprehensive term? Our national honor and glory which, be it remembered, are to be "transmitted as well as enjoyed," are involved. In building up the bric of our commercial prosperity, let us not filch the corner stone. Let it not be said of us, in future ages, that we ingloriously availed ourselves of a stock of scientific knowledge, to which we had not contributed our quota — that we shunned as a people to put our shoulder to the wheel — that we reaped where we had never sown. It is not to be controverted that such has been hitherto the case. We have followed in the rear of discovery, when a sense of our moral and polidcal responsibility should have impelled us in its van. Mr. Reynolds, in a letter to which we have already referred, deprecates this servile dependence upon foreign research in the following nervous and emphatic language.

The commercial nations of the earth have done much, and much remains to be accomplished. We stand a solitary instance among those who are considered commercial, as never having put forth a particle of strength or expended a dollar of our money, to add to the accumulated stock of commercial and geographical knowledge, except in partially exploring our own territory.

When our naval commanders and hardy tars have achieved a victory on the deep, they have to seek our harbors, and conduct their prizes into port by tables and charts furnished perhaps by the very people whom they have vanquished.

Is it honorable in the United States to use, forever, the knowledge furnished by others, to teach us how to shun a rock, escape a shoal, or find a harbor; and add nothing to the great mass os information that previous ages and other nations have brought to our hands. * *

The exports, and, more emphatically, the imports of the United States, her receipts and expenditures, are written on every pillar erected by commerce on every sea and in every clime; but the amount of her subscription stock to erect those pillars and for the advancement of knowledge is no where to be found.

* * * * * *

Have we not then reached a degree of mental strength, which will enable us to find our way about the globe without leading-strings? Are we forever to take the highway others have laid out for us, and fixed with mile-stones and guide boards? No: a time of enterprise and adventure must be at hand, it is already here; and its march is onward, as certain as a star approaches its zenith.

It is delightful to find that such independent statements and opinions as the above, have been approved, and acted upon by Congress, and that our President with a wisdom and promptitude which do him honor, is superintending and fecifitating the execution of legislative design. We extract the following announcement from the Washington Globe.

Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas. — We learn that the President has given orders to have the exploring vessels fitted out, with the least possible delay. The appropriation made by Congress was ample to ensure all the great objects contemplated by the expedition, and the Executive is determined that nothing shall be wanting to render the expedition in every respect worthy the character and great commercial resources of the country.

The frigate Macedonian, now undergoing thorough repairs at Norfolk, two brigs of two hundred tons each, one or more tenders, and a store ship of competent dimensions, is, we understand, the force agreed upon, and to be put in a state of immediate preparation.

Captain Thomas A. C. Jones, an officer possessing many high qualities for such a service, has been appointed to the command; and officers for the other vessels will be immediately selected.

The Macedonian has been chosen instead of a sloop of war, on account of the increased accomodations she will afford the scientific corps, a department the President has determined shall be complete in its organization, including the ablest men that can be procured, so that nothing within the whole range of every department of natural history and philosophy shall be omitted. Not only on this account has the frigate been selected, but also for the purpose of a more extended protection of our whalemen and traders; and to impress on the minds of the natives a just conception of our character, power, and policy. The frequent disturbances and massacres committed on our seamen by the natives inhabiting the islands in those distant seas, make this measure the dictate of humanity.

We understand also, that to J. N. Reynolds, Esq. the President has given the appointment of Corresponding Secretary to the expedition. Between this gentlaman and Captain Jones there is the most friendly feeling and harmony of action. The cordiality they entertain for each other, we trust will be felt by all, whether citizen or officer, who shall be so fortunate as to be connected with the expedition.

Thus it will be seen, steps are being taken to remove the reproach of our country alluded to by Mr. Reynolds, and that that gendeman has been appointed to the highest civil situation in the expedition; a station which we know him to be exceedingly well qualified to fill. The liberality of the appropriation for the enterprise, the strong interest taken by our energetic chief magistrate in its organization, the experience and intelligence of the distinguished commander at its head, all promise well for its successful termination. Our most cordial good wishes will accompany the adventure, and we trust that it will prove the germ of a spirit of scientific ambition, which, fostered by legislative patronage and protection, should build up for us a name in nautical discovery commensurate with our moral, political, and commercial position among the nations of the earth. Southern Literary Messenger, August 1835: 587-89.

//////////////////////////////////////

ハリソン版のE-text by Google @Internet Archive―― <http://www23.us.archive.org/stream/completeworksed00harrgoog#page/n108/mode/2up> 〔かなり長い引用がたくさん省略されていたことがわかります〕

夜の底 The Bottom of the Night [Marginalia 余白に]

〔……〕下人は、剥ぎとった 檜皮色 ( ひわだいろ ) の着物をわきにかかえて、またたく間に急な梯子を夜の底へかけ下りた。

しばらく、死んだように倒れていた老婆が、死骸の中から、その裸の体を起こしたのは、それから間もなくの事である。〔……〕外には、ただ、黒洞々(こくとうとう)たる夜があるばかりである。

――芥川龍之介「羅生門」(大正4年)

国境のトンネルを抜けると、窓の外の夜の底が白くなった。

――川端康成「夕景色の鏡」(昭和10年)

国境のトンネルを抜けると雪国であった。夜の底が白くなった。

――川端康成『雪国』(昭和23年)

「羅生門」の結末近くの文章と『雪国』の冒頭の文章と。「羅生門」も推敲が行なわれたようだけれど、それはもっぱらこのあとの結びの一文(「下人の行方は、誰も知らない。」← 「下人は、既に、雨を冒して京都の町へ強盗を働きに急いでゐた。」← 「下人は、既に、雨を冒して、京都の町へ強盗を働きに急ぎつつあった。」)であるらしい。ハシゴを降下して、さらに外の闇の世界へ、という下降運動と「底」はつながっているのでしょう。改訂も、京都という明示的な場所から、読者に想像が委ねられた「闇の世界」へと誘うものかもしれぬ)。 『雪国』の一文は、むかしはトンネルの先(奥)だとイメジしていたのだけれど、ちがうのでした。

「夜の底」は、紙の辞典には容易に見つからないけれど、Web辞典には「デジタル大辞泉 夜の底の用語解説 - 夜の深い闇をいう語。「―に姿を消す」」などとコトバンクやgoo辞書に載っている(『大辞泉』にはあるのかな)。へんなの。

「夜の底」は、ともに外国語(英語)に堪能だった二人の作家が翻訳調に使った日本語なのかしら。

しかし Edward Seidensticker の英訳 Snow Country は "bottom of the night" というフレーズを使っていない――

The train came out of the long tunnel into the snow country. The earth lay white under the night sky.

サイデンステッカーの英訳が説明しているのは、この、「夜の底」の「白」さというのは、つまり雪のことだということで、「底」とは「夜の空」の下=地上ということだ。

けれども、William J. Tyler という研究者は、Mary Ann Gillies et al., ed., Pacific Rim Modernisms (U of Toronto P, 2009) におさめられた論文 "Fission/Fusion: Modanizumu in Japanese Fiction" のなかで、説明的だけれども、「直訳」的に "bottom of the night" を入れた、私訳を挙げている(207ページ)。――

/////////////////////////////

芥川龍之介「羅生門」@青空文庫 <http://www.aozora.gr.jp/cards/000879/files/127_15260.html>

松野町夫「『雪国』を読めば、日本語と英語の発想がわかる!」『リベラル21』2008.05.29 <http://lib21.blog96.fc2.com/?no=357>

ポーが書評した本 (29) ジェレマイア・レノルズの『太平洋ならびに南海への調査探検航海についての弁論』 (1836) Books Reviewed by Poe (29): _Address on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas_ by J. Reynolds [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

同じことを繰り返して書きます。ポーの長篇小説『アーサー・ゴードン・ピム』(1837-38) のソースとして、第16章の本文中でポー自身が言及しているのが Benjamin Morrell, Narrative of Four Voyages to the South Seas and Pacific, 1822-1831 (1832) と J. N. Reynolds, Address on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas (1836) ですけれど、レノルズについてはこのパンフレットも含めて3冊の著作の書評を書いており、いずれの本も『ピム』に影響が認められます。

(1) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Voyage of the Potomac (1835): reviewed in the June 1835 SLM [Southernn Literary Messenger].

(2) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Report of the Committee on Naval Affairs (1836): reviewed in the August 1836 SLM.

(3) Jeremiah N. Reynolds, Address on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas (1836): reviewed in the January 1837 SLM.

で、3つめなのですけれど、1837年正月の3日に、ポーは『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』社主のホワイトから、解雇されます。ですので、編集者として同誌にポーが文章を書いた、最後の号が1837年1月号なのでした。

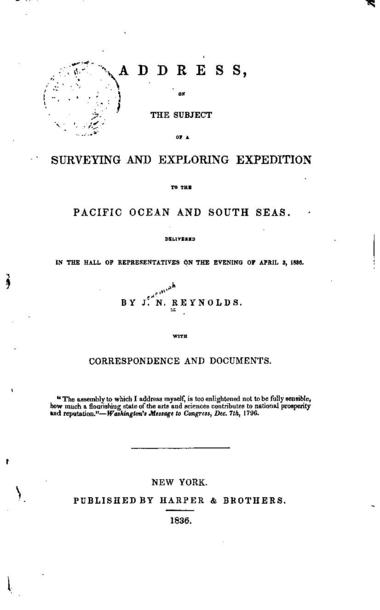

Address, on the Subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the

Pacific Ocean and South Seas. Delivered in the Hall of Representatives

on the Evening of April 3, 1836. By J. N. Reynolds. With Correspondence

and Documents. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1836. 300pp.

E-text <http://archive.org/stream/addressonsubjec00reyngoog#page/n9/mode/2up> 〔ただし、偶数ページにいくらか脱落あり〕

ポーの書評は前年のと同様に "South-Sea Expedition" を見出しとしています。これは、南洋(南太平洋)探検旅行がトピカルな話題であったことを示しています。

Address on the subject of a Surveying and Exploring Expedition to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas. Delivered in the Hall of Representatives on the Evening of April3, 1836. By J. N. Reynolds. With Correspondence and Documents. New York: Published by Harper and Brothers.

In the Messenger for last August we spoke briefly on this head. What we then said was embraced in the form of a Critical Notice on the "Report (March 21, 1836,) of the Committee on Naval Affairs to whom was referred Memorials from sundry citizens of Connecticut interested in the Whale Fishery, praying that an exploring expedition be fitted in the Whale Fishery, praying that an exploring expedition be fitted out to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas." It is now well known to the community that this expedition, the design of which has been for ten years in agitation, has been authorized by Congress; sanctioned, and liberally provided for, by the Executive; and will almost immediately set sail. The public mind is at length thoroughly alive on the subject, and in touching upon it now, we merely propose to give, if possible, such an outline of the history, object, and nature of the projet, as may induce the reader to examine, for himself, the volume whose title forms the heading, of this article. Therein Mr. Reynolds has embodied a precise and full account of the whole matter, with every necessary document and detail.

In beginning we must necessarily begin with Mr. Reynolds. He is the originator, the persevering and indomitable advocate, the life, the soul of the design. Whatever, of glory at least, accrue therefore from the expedition, this gentleman, whatever post he may occupy in it, or whether none, will be fairly entitled to the lion's share, and will as certainly receive it. He is a native of Ohio, where his family are highly respectable, and where he was educated and studied the law. He is known, by all who know him at all, as a man of the loftiest principles and of unblemished character. "His writings," to use the language of Mr. Hamer on the floor of the House of Representatives, "have attracted the attention of men of letters; and literary societies and institutions have conferred upon him some of the highest honors they had to bestow." For ourselves, we have frequently borne testimony to his various merits as a gentleman, a writer and a scholar.

It is now many years since Mr. R's attention was first attracted to the great national advantages derivable from an exploring expedition to the South Sea and the Pacific; time has only rendered the expediency of the undertaking more obvious. To-day the argument for the design is briefly as follows. No part of the whole commerce of our country is of more importance than that carried on in the regions in question. At the lowest estimate a capital of twelve millions of dollars is actively employed by one branch of the whale fishery alone; and there is involved in the whole business, directly and collaterally, not less probably than seventy millions of property. About one tenth of the entire navigation of the United States is engaged in this service ― from 9 to 12 000 seamen, and from 170 to 200,000 tons of shipping. The results of the fishery are in the highest degree profitable ― it being not a mere interchange of commodities, but, in a great measure, the creation of wealth, by labor, from the ocean. It produces to the United States an annual income of from five to six millions of dollars. It is a most valuable nursery for our seamen, rearing up a race of hardy and adventurous men, eminently fit for the purposes of the navy. This fishery then is of importance ― its range may be extended ― at all events its interests should be protected. The scene of its operations, however, is less known and more full of peril than any other portion of the globe visited by our ships. It abounds in islands, reefs and shoals unmarked upon any chart ― prudence requires that the location of these should be exactly defined. The savages in these regions have frequently evinced a murderous hostility ― they should be conciliated or intimidated. The whale, and more especially all furred animals, are becoming scarce before the perpetual warfare of man ― new generations will be found in the south, and the nation first to discover them will reap nearly all the rich benefits of the discovery. Our trade in ivory, in sandal-wood, in biche le-mer, in feathers, in quills, in seal-oil, in porpoise oil, and in seal elephant oil, may here be profitably extended. Various other sources of commerce will be met with, and may be almost exclusively appropriated. The crews, or at least some portion of the crews, of many of our vessels known to be wrecked in this vicinity, may be rescued from a life of slavery and despair. Moreover, we are degraded by the continual use of foreign charts. In matters of mere nautical or geographical science, our government has been hitherto supine, and it is due to the national character that in these respects something should be done. We have now a chance of redeeming ourselves in the Southern Sea. Here is a wide field open and nearly untouched ― " a theatre peculiarly our own from position and the course of human events." Individual enterprize, even acting especially for the purpose, cannot be expected to accomplish all that should be done-dread of forfeiting insurance will prevent our whale-ships from effecting any thing of importance incidentally-and our national vessels on general service have elsewhere far more than they can efficiently attend to. In the meantime our condition is prosperous beyond example, our treasury is overflowing, a special national expedition could accomplish every thing desired, the expense of it will be comparatively little, the whole scientific world approve it, the people demand it and thus there is a multiplicity of good reasons why it should immediately be set on foot.

Ten years ago these reasons were still in force, and Mr. Reynolds lost no opportunity of pressing them upon public attention. By a series of indefatigable exertions he at length succeeded in fully interesting the country in his scheme. Commodore Downes and Captain Jones, with nearly all the officers of our navy, gave it their unqualified approbation. Popular assemblages in all quarters spoke in its favor. Many of our commercial towns and cities petitioned for it. It was urged in reports from the Navy and Messages from the Executive Department. The East India Marine Society of Massachusetts, all of whose members by the constitution must have personally doubled either Cape Horn or the Cape of Good Hope, were induced to get up a memorial in its behalf; and the legislatures of eight different states-of New York New Jersey, Rhode Island, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Ohio, North Carolina, and we are happy to add, of Virginia, recommended the enterprize in the most earnest manner to the favorable consideration of Congress.

As early as January 1828, Mr. Reynolds submitted to the Speaker of the House of Representatives, a letter upon the subject accompanied with memorials and petitions. Among these memorials was one from Albany, dated October 19, 1827, and signed by his Excellency Nathaniel Pitcher, lieutenant governor of the State of New York; the honorable Erastus Root, speaker of the house of delegates; and by nearly all the members of the legislature. Another, dated Charleston, south Carolina, May 31, 1827, was signed by the mayor of the city; the president of the chamber of commerce; and by a very long list of respectable citizens. A third was dated Raleigh, North Carolina, December 24th, 1827, and contained the signatures of his Excellency James Iredell, the governor, the honorable B. Yancey, speaker of the senate; the honorable James Little, speaker of the house of commons; and a large proportion of each branch of the legislature. A fourth was dated Richmond, Virginia, January 1st, 1828, and was sustained by a great number of the most influential inhabitants of Virginia; by the honorable Linn Banks, speaker of the house of delegates; and by a majority of the delegates themselves. For reference, a majority of the delegates themselves. For reference, Mr. Reynolds handed in at the same period a preamble and resolution of the Maryland Assembly, approving in the strongest terms the contemplated expedition. The matter was thus for the first time, we believe, brought into a shape for the official cognizance of the government.

The letter was referred to the committee on Naval Affairs. That body made application to Mr. R. for a statement, in writing, of his views. It was desired that this statement should contain his reasons for general results, a deference to authorities for specific facts, as well as a tabular statement of the results and facts, so far as they might be susceptible of being stated in such form. To this application Mr. R. sent a brief yet comprehensive reply, embracing a view of the nature and extent of our whale-fisheries, and the several trades in the seal otter skin, the fur seal skin, the ivory sea elephant tooth, land animal fur, sandal wood, and feathers, together with observations on the general benefits resulting from these branches of commerce, independent of the wealth they bring into the country.

The Secretary of the Navy was also called upon for his opinion. In his reply he strongly commended the design, using the main arguments we have already adduced. He stated, moreover, that Mr. Reynolds' estimate of the value of our commerce in the regions in question, had been much augmented, in the view of the department, through the reports, made under his orders, of our naval officers, who had commanded vessels of war in the Pacific.

Nothing was done, however, until the next session of Congress. A bill was then proposed but did not become a law. In consequence of its failure, the House of Representatives passed a resolution requesting the President of the United States "to send one of our small vessels to the Pacific Ocean and South Seas to examine the coast, islands harbors, shoals and reefs in those seas, and to ascertain their true situation and description" and authorizing the use of such facilities as could be afforded by the Navy Department without further appropriation during the year. There was, however, no suitable national vessel in condition, at the time, to be despatched upon the service. The Peacock, therefore, was placed at the New York Navy yard, to be repaired and fitted out, and an additional vessel of two hundred tons engaged, upon the agreement that Congress should be recommended to authorized the purchase ― the vessel to be returned if the recommendation were not approved. These arrangements the Secretary of the Navy communicated to Congress in November, 1828. A bill now passed one house, but was finally lost.

Mr. Reynolds did not cease from his exertions. The subject of the expedition was not effectually resumed, however, until January 1835. Mr. Dickerson then transmitted to Congress, a Report by Mr. R., dated September 24th, 1828. This report had been drawn up at the request of Mr. Southard, in June, when that gentleman was called upon by the Committee on Naval Affairs. It occupies about forty pages of the volume now before us, and speaks plainly of the assiduity and energy of the reporter. He repaired, immediately, upon Mr. Southard's expressing a wish to that effect, to New London, Stonington, New-Bedford, Edgartown, Nantucket, and other places where information might be found of the pacific Ocean and South Seas. His desire was to avail himself of personal data, afforded by the owners and masters of the whaling vessels sailing from those ports. His main objects of inquiry were the navigation, geography and topography presented by the whole range of the seas form the Pacific to the Indian and Chinese oceans, with the extent and nature of our commerce and fisheries in those quarters. He found that "all he had before heard was confirmed by a long train of witnesses, and that every calculation he had previously made fall very far short of the truth." In February 1835, the Committee on Commerce strongly recommended Mr. Reynolds' design, and in March 1836 the committee on naval Affairs made a similar report. On May the 10th, a bill authorizing the expedition, but leaving nearly every thing to the discretion of the Chief magistrate, finally passed both houses of congress. The friends of the bill could have desired nothing better. The President gave orders forthwith to have the exploring vessels fitted out with the least possible delay. The frigate Macedonian, now nearly ready, will be the main vessel in the enterprize. Captain Thomas Ap C. Jones will command her. She has been chosen instead of a sloop of war, on account of the increased accommodations she will afford the scientific corps, which is to be complete in its organization, including the ablest men to be procured. She will give too, extended protection to our commerce in the seas to be visited, and her imposing appearance will avail more to overawe the savages, and impress upon them a just idea of our power, than even a much larger real force distributed among vessels of less magnitude. She will be accompanied by two brigs of two hundred tons each, two tenders, and a store-ship.

In regard to the time of sailing there can be but little choice ― the vessels will put to sea as soon as every thing is ready. The scientific corps, we believe, is not yet entirely filled up; nor can it be well organized until the preparations in the frigate are completed. Many gentlemen of high celebrity, however, have already offered their services. In the meantime, Lieutenant Wilkes of the Navy has been despatched to England and France, for the purpose of purchasing such instruments for the use of the expeditions, as cannot readily be procured in this country. In all quarters he has met with the most gratifying reception, and with ardent wishes for the success of the contemplated enterprize.

Mr. Reynolds has received the highest civil post in the expedition ― that of corresponding secretary. It is presumed that he will draw up the narrative of the voyage, (to be published under patronage of government) embodying, possibly, and arranging in the same book, the several reports or journals of the scientific corps. How admirable well he is qualified for this task, no person can know better than ourselves. His energy, his love of polite literature, his many and various attainments, and above all, his ardent and honorable enthusiasm, point him out as the man of all men for the execution of the task. We look forward to this finale ― to the published record of the expedition ― with an intensity of eager expectation, which we cannot think we have ever experienced before.

And it has been said that envy and ill ― will have been already doing their work--that the motives and character of Mr. Reynolds have been assailed. This is a matter which we fully believe. It is perfectly in unison with the history of all similar enterprizes, and of the vigorous minds which have conceived, advocated, and matured them. It is hardly necessary, however, to say a word upon this topic. We will not insult Mr. Reynolds with a defense. Gentlemen have impugned his motives ― have these gentlemen ever seen him or conversed with him half an hour?

We close this notice by subjoining two interesting extracts from the eloquent Address now before us:

It is the opinion of some, as we are aware, that matters of this description are best left to individual enterprize, and that the interference of government is unnecessary. Such persons do not reflect, as they ought, that all measures of public utility which from any cause cannot be accomplished by individuals, become the legitimate objects of public care, in reference to which the government is bound to employ the means put into its hands for the general good. Indeed, while there remains a spot of untrodden earth accessible to man, no enlightened, and especially commercial and free people, should withhold its contributions for exploring it, wherever that spot may be found on the earth, from the equator to the poles!

Have we not shown that this expedition is called for by our extensive interests in those seas ― interests which, from small beginnings, have increased astonishingly in the lapse of half a century, and which are every day augmenting and diffusing their beneficial results throughout the country? May we not venture on still higher grounds? Had we no commerce to be benefited, would it not still be honorable; still worthy the patronage of Congress; still the best possible employment of a portion of our naval force?

Have we not shown, that this expedition is called for by national dignity and honor? Have we not shown, that our commanding position and rank among the commercial nations of the earth, makes it only equitable that we should take our share in exploring and surveying new islands, remote seas, and, as yet, unknown territory? Who so uninformed as to assert that all this has been done? Who so presumptuous as to set limits to knowledge, which, by a wise law of Providence, can never cease? As long as there is mind to act upon matter, the realms of science must be enlarged; and nature and her laws be better understood, and more understandingly applied to the great purpose of life. If the nation were oppressed with debt, it might, indeed, it would, still be our duty to do something, though the fact, perhaps, would operate as a reason for a delay of action. But have we any thing of this kind to allege, when the country is prosperous, without a parallel in the annals of nations?

Is not every department of industry in a state of improvement? Not only two, but a hundred blades of grass grow where one grew when we became a nation; and our manufactures have increased, not less to astonish the philosopher and patriot, than to benefit the nation; and have not agriculture and manufactures, wrought up by a capital of intelligence and enterprize, given a direct impulse to our commerce, a consequence to our navy? And if so, do they not impose new duties on every statesman?

Again, have we not shown that this expedition is demanded by public opinion, expressed in almost every form? Have not societies for the collection and diffusion of knowledge, towns and legislatures, and the commanding voice of public opinion, as seen through the public press, sanctioned and called for the enterprize? Granting, as all must, there is no dissenting voice upon the subject, that all are anxious that our country should do something for the great good of the human family, is not now the time, while the treasury, like the Nile in fruitful seasons, is overflowing its banks? If this question is settled, and I believe it is, the next is, what shall be the character of the expedition? The answer is in the minds of all--one worthy of the nation? And what would be worthy of the nation? Certainly nothing on a scaled that has been attempted by any other country. If true to our national character, to the spirit of the age we live in, the first expedition sent out by this great republic must not fall short in any department ― from a defective organization, or from adopting too closely the efforts of other nations as models for our own. We do, we always have done things best, when we do them in our own way. The spirit evinced by others is worthy of all imitation; but not their equipments. We must look at those seas; what we have there; what requires to be done; ― and then apply the requisite means to accomplish the ends. It would not only be inglorious simply to follow a track pointed out by others, but it could never content a people proud of their fame and rejoicing in their strength! They would hurl to everlasting infamy the imbecile voyagers, who had only coasted where others had piloted. No; nothing but a goodly addition to the stock of present knowledge, would answer for those most moderate in their expectations.

But, not only to correct the errors of former navigators, and to enlarge and correct the charts of every portion of sea and land that the expedition might visit, and other duties to which we have alluded; but also to collect, preserve, and arrange every thing valuable in the whole range of natural history, from the minute madrapore [madrepore イシサンゴ?]to the huge spermaceti, and accurately to describe that which cannot be preserved; to secure whatever may be hoped for in natural philosophy to examine vegetation, from the hundred mosses of the rocks, throughout all the classes of shrub, flower and tree, up to the monarch of the forest; to study man in his physical and mental powers, in his manners, habits, disposition, and social and political relations; and above all, in the philosophy of his language, in order to trace his origin from the early families of the old world; to examine the phenomena of winds and tides, of heat and cold, of light and darkness; to add geological to other surveys, when it can be done in safety; to examine the nature of soils ― if not to see if they can be planted with success ― yet to see if they contain any thing which may be transplanted with utility to our own country; in fine, there should be science enough to bear upon every thing that may present itself for investigation.

How, it may be asked, is all this to be effected? By an enlightened body of naval officers, joining harmoniously with a corps of scientific men, imbued with the love of science, and sufficiently learned to pursue with success the branches to which they should be designated. This body of men should be carefully selected, and made sufficiently numerous to secure the great objects of the expedition. These lights of science, and the naval officers, so far from interfering with each other's fame, would, like stars in the milky-way, shed a lustre on each other, and all on their country!

These men may be obtained, if sufficient encouragement is offered as an inducement. They should be well paid. Scholars of sufficient attainments to qualify them for such stations, do not hang loosely upon society; they must have fixed upon their professions or business in life: and what they are called to do, must be from the efforts of ripe minds; not the experiments of youthful ones to prepare them for usefulness. If we have been a by-word and a reproach among nations for pitiful remuneration of intellectual labors, this expedition will afford an excellent opportunity of wiping it away. The stimulus of fame is not a sufficient movie for a scientific man to leave his family and friends, and all the charms and duties of social life, for years together; but it must be united to the recompense of pecuniary reward, to call forth all the powers of an opulent mind. The price you pay will, in some measure, show your appreciation of such pursuits. We have no stars and ribands, no hereditary titles, to reward our men of genius for adding to the knowledge or to the comfort of mankind and to the honor of the nation. We boast of our men of science, our philosophers, and artists, when they have paid the last tribute to envy by their death. When mouldering in their graves, they enjoy a reputation, which envy and malice and detraction may hawk at and tear but cannot harm! Let us be more just, and stamp the value we set on science in a noble appreciation of it, and by the price we are willing to pay.

It has been justly remarked, that those who enlighten their country by their talents, strengthen it by their philosophy, enrich it by their science, and adorn it by their genius, are Atlases, who support the name and dignity of their nation, and transmit it unimpaired to future generations. Their noblest part lives and is active, when they are no more; and their names and contributions to knowledge, are legacies bequeathed to the whole world! To those who shall thus labor to enrich our country, if we would be just, we must be liberal, by giving to themselves and families an honorable support while engaged in these arduous duties!

If the objects of the expedition are noble, if the inducements to undertake it are of a high order ― and we believe there can be no difference of opinion on this point ― most assuredly the means to accomplish them should be adequate. No narrow views, no scanty arrangements, should enter the minds of those who have the planning and directing of the enterprize. At such a time, and in such a cause, liberality is economy and parsimony is extravagance.

Again, if the object of the expedition were simply to attain a high southern latitude, then two small brigs or barks would be quite sufficient. If to visit a few points among the islands, a sloop of war might answer the purpose. But are these the objects? We apprehend they only form a part. From the west coast of South America, running down the longitude among the islands on both sides of the equator, though more especially south, to the very shores of Asia, is the field that lies open before us, independent of the higher latitudes south, of which we shall speak in the conclusion of our remarks. Reflecting on the picture we have sketched of our interests in that immense region, all must admit, that the armament of the expedition should be sufficient to protect our flag; to succor the unfortunate of every nation, who may be found on desolate islands, or among hordes of savages; a power that would be sufficient by the majesty of its appearance, to awe into respect and obedience the fierce and turbulent, and to give facilities to all engaged in the great purposes of the voyage. The amount of this power is a question upon which there can be but little difference of opinion, among those thoroughly acquainted with the subject; the best informed are unanimous in their opinion, that there should be a well-appointed frigate, and five other vessels ―twice that number would find enough, and more than they could do. The frigate would form the nucleus, round which the smaller vessels should perform the labors to which you will find pointed out in all the memorials and reports hitherto made on this subject, and which may be found among the printed documents on your tables. Some might say, and we have heard such things said, that this equipment would savor of individual pride in the commander; but they forget that the calculations of the wise are generally secured by the strength of their measure. The voyage is long ― the resting places uncertain, which makes the employment of a storeship, also a matter of prudence and economy. It would not do to be anxious about food, while the expeditions was in the search of an extended harvest of knowledge.

The expectations of the people of the United States from such an expedition, most unquestionably would be great. From their education and past exertions through all the history of our national growth, the people are prepared to expect that every public functionary should discharge his duty to the utmost extent of his physical and mental powers. They will not be satisfied with any thing short of all that men can perform. The appalling weight of responsibility of those who serve their country in such an expedition, is strikingly illustrated by the instructions given to Lewis and Clarke, in 1803, by President Jefferson. The extended views and mental grasp of this distinguished philosopher no one will question, nor can any one believe that he would be unnecessarily minute.

The sage, who had conceived and matured the plan of the expedition to the far west, in his instructions to its commander under his won signature, has left us a model worthy of all imitation. With the slight variations growing out of time and place, how applicable would those instructions be for the guidance of the enterprize we have at present in view? The doubts of some politicians, that this government has no power to encourage scientific inquiry, most assuredly had no place in the mind of that great apostle of liberty, father of democracy and

strict constructionist! We claim no wider range than he has sanctions; including as he does, animate and inanimate nature, the heavens above and all on the earth beneath! The character and value of that paper are not sufficiently known. Among all the records of his genius, his patriotism, and his learning, to be found in our public archives, this paper deserves to take, and in time will take rank, second only to the Declaration of our Independence. The first, embodied the spirit of our free institutions, and self-government; the latter, sanctioned those liberal pursuits, without a just appreciation of which our institutions cannot be preserved, or if they can, would be scarcely worth preserving. [pp. 69-76]

To complete its efficiency, individuals from other walks of life, we repeat, should be appointed to participate in its labors. No professional pique, no petty jealousies, should be allowed to defeat this object. The enterprize should be national in its object, and sustained by the national means, ― belongs of right to no individual, or set of individuals, but to the country and the whole country; and he who does not view it in this light, or could not enter it with this spirit, would not be very likely to meet the public expectations were he entrusted with the entire control.

To indulge in jealousies, or feel undue solicitude about the division of honors before they are won, is the appropriate employment of carpet heroes, in whatever walk of life they may be found. The qualifications of such would fit them better to thread the mazes of the dance, or to shine in the saloon, than to venture upon an enterprize requiring men, in the most emphatic sense of the term.

There are, we know, many, very many, ardent spirits in our navy ― many whom we hold among the most valued of our friends ― who are tired of inglorious ease, and who would seize the opportunity thus presented to them with avidity, and enter with delight upon this new path to fame.

Our seamen are hardy and adventurous, especially those who are engaged in the seal trade and the whale fisheries; and innured as they are to the perils of navigation, are inferior to none on earth for such a service. Indeed, the enterprize, courage, and perseverance of American seamen are, if not unrivaled, at least unsurpassed. What man can do, they have always felt ready to attempt, ― what man has done, it is their character to feel able to do, ― whether it be to grapple with an enemy on the deep, or to pursue their gigantic game under the burning line, with an intelligence and ardor that insure success, or pushing their adventurous barks into the high southern latitudes, to circle the globe within the Antarctic circle, and attain the Pole itself; yea, to cast anchor on that point where all the meridians terminate, where our eagle and star-spangled banner may be unfurled and planted, and left to wave on the axis of the earth itself! ― where, amid the novelty, grandeur and sublimity of the scene, the vessels, instead of sweeping a vast circuit by the diurnal movements of the earth, would simply turn round once in twenty-four hours!

We shall not discuss, at present, the probability of this result, though its possibility might be easily demonstrated. If this should be realized, where is the individual who does not feel that such an achievement would add new lustre to the annals of American philosophy, and crown with a new and imperishable wreath the nautical glories of our country! [pp. 98-99]

青字の長い引用は、SLM の誌面では、小さな活字になっています。