ポーが書評した本 (1) メアリー・グリフィスの『キャンパーダウン』 (1836) Books Reviewed by Poe (1): "Camperdown; or, News from Our Neighbourhood" [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

ウツウツとする記事ばかり書いているので、心機一転、新規蒔き直しをはかるべく、新たなカテゴリーをうちたてます。エドガー・アラン・ポー (1809-49) が書評を書いた本について。趣旨と意義などは (1) 批評家としてのポーの仕事の広がりを見、 (2) アメリカ19世紀前半の文壇・文学状況をポーを通して展望する、が、そのために、(3) ポーが書評を書いた本の E-text をリンクして容易に読めるようにする(おたがいに読める能力と時間があればの話だが)。 (4) 順序は思いつくまま、気の向くまま。 (5)文章はなるたけ短く(なんか書きたくなったらなるたけ別記事で)。・・・・・・下の記事、書きかけたのが消えてしまい(とほほ)、書き直したら、なんか長くなっていました(わはは)。

☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

Camperdown; or, News from Our Neighbourhood―Being a Series of Sketches, by the author of "Our Neighborhood," &c. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard.

〔メアリー・グリフィス著〕『キャンパーダウン――我らが近隣からの便り』

6篇からなる短篇小説集―― (1) "Three Hundred Years Hence"―(2) "The Surprise"―(3) "The Seven Shanties"―(4) "The Little Couple"―(5) "The Baker's Dozen"―(6) "The Thread and Needle Store"

E-text at Internet Archive [University of California Libraries; MSN] <http://www.archive.org/stream/camperdownornews00grifrich#page/n9/mode/2up>

ポーの書評は、『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー The Southern Literary Messenger』1836年7月号所収(短評)。

19世紀は、男でも女でも匿名にして「XXXX〔前作や前前作名〕の著者による By the Author of XXXX」という表記だけで、著者名が本には記述されない場合がけっこうあったのだけれど、そういうのって、ほんとうに匿名だったのか、実は口コミ的に知られている作家も多くいたのか、よくわかりません。この短篇集も著者名は本本体には出てきません。タイトルページ――

本は女性(Mrs. William Minot という Lady)に献じられていて、献辞のなかには「ボストンでは女性が高い敬意と評価を受けている」とかなんとか、ボストン嫌いのポーの頭にきそうなことも書かれているのだけれど、そうなると作者も女性と想像されるのだろうか。

ともあれ、ポーの書評の文章のなかにも著者名は出てこないです。しかし、作者はメアリー・グリフィス Mary Griffith, 1772-1846 という女性作家・農学者(園芸家)・科学者でした。このひとについて語ると長くなるので、ここでは文学関係でのみ補足的に書いておきます。

今日(こんにち)、メアリー・グリフィスは、女性最初のユートピアSF小説を書いたひととして、一部で、知られています。その評価はもっぱら、この短篇集の冒頭の作品「此後三百年 Three Hundred Years Hence」に拠っている(らしい)。英語のWikipedia 参照―― "Mary Griffith" <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Griffith>。

ポーは、書評の大半をこの短篇小説についての解説に費やしています。ただし、冒頭で「Mercier の模倣」と書くように、常套的なものと見ていて、必ずしも作品自体を評価しているわけではない(かもしれない)。――Three Hundred Years Since is an imitation of Mercier's "Lan [sic] deux milles quatre cents quarante," the unaccredited parent of a great many similar things.

Mercier はフランスの劇作家、ジャーナリストのルイ・セバスチャン・メルシエ Louis Sébastien Mercier, 1740-1814 です。メルシエはディドロにならって戯曲を書き、演劇論 Essai sur l'art dramatique (1873) でディドロの演劇理論を発展させた、ロマン主義の先駆者ですが、1870年に発表した未来小説が L'An 2440 でした。長いタイトルとその英訳題は、ウィキペディアによれば、 L'An 2440, rêve s'il en fut jamais (literally, "The Year 2440: A Dream If Ever There Was One"; translated into English as Memoirs of the Year Two Thousand Five Hundred) 。

眠って目が覚めたら過去だった、とか未来だったとか、眠り(オチ的には夢)と時間旅行(タイム・トラベル)とユートピアないし逆ユートピア(ディストピア)思想が三位一体となった枠組みは、半世紀後のマーク・トウェインの『アーサー王宮廷のコネティカット・ヤンキー』とかエドワード・ベラミーの『顧みれば』などで復活(?)するものですけど、19世紀前半に既に「常套」的な感覚があったところが興味深い(むろんポー自身、未来からの手紙(「メロンタ・タウタ」)とか過去からの眠り(「ミイラとの論争」)とか、関心が重なるところです)。

ポーがあらすじを紹介しているように、フィラデルフィアからニューヨークへむかう旅の前夜、眠りに落ちた主人公が目覚めると未来にいる。東部の未来のありさまが描かれることになります。

ウィキペディアの記事が、本文ではないけれど、参考url としてリンクしている、"Mary Griffith's Pioneering Vision: Three Hundred Years Since" <http://www.highbeam.com/doc/1G1-66454600.html> という論文(のさわり)は、文学作品としての質以上に、男であるとか女であるとかにやたらこだわっているのだけれど、女性性がユートピアのヴィジョンに有意義な刻印をしるしているのかどうかは、読んでから考えたいと思います。

☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

ところで、このシリーズは、ポー関係の事典類(具体的には、Frederick S. Frank and Anthony Magistrale, The Poe Encyclopedia (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1997) とか、Dawn B. Sova, Edgar Allan Poe A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work (New York: Facts on File, 2001) など)をタネ本として書いてやれ、と思っておったのですが、『ポー百科事典』のこの項目の記述は、つぎのようです。――

Review of Mary Griffith's collection of six tales appearing in The Southern Literary Messenger for July 1836. Poe found the stories "The Little Couple" and "The Thread and Needle Store" full of "originality of thought and manner" and several others "sufficiently outré." (アメリカの女性作家メアリー・グリフィスの、6篇の物語からなる短篇集の書評。『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』誌1836年7月号掲載。ポーは短篇「小さなカップル The Little Couple」と「裁縫屋 The Thread and Needle Store」の2篇について「思想と手法の独創性」があると言い、他の数篇が「十分に奇抜outré」と評した。)

最後に原文を全文載せておきますけれど、上の記述は、明らかな読み間違いで、ポーが「思想と手法の独創性」があると言うのは短篇集全体 ("It") ですし、ポーが奇抜と言っているのは、冒頭の短篇小説「此後三百年」の後半部における、フィラデルフィアからニューヨークにわたる300年の差異の記述についてのことです。

ちょっと呆れました。

In "Our Neighbo[u]rhood" published a few years ago, the author promised to give a second series of the work, including brief sketches of some of its chief characters. The present volume is the result of the promise, and will be followed up by others―in continuation. We have read all the tales in Camperdown with interest, and we think the book cannot well fail being popular. It evinces originality of thought and manner―with much novelty of matter. The tales are six in number; Three Hundred Years Hence―The Surpise―The Seven Shanties―The Little Couple―The Baker's Dozen―and The Thread and Needle Store[.] Three Hundred Years Hence is an imitation of Mercier's "Lan deux milles quatre cents quarante," the unaccredited parent of a great many similar things. In the present instance, a citizen of Pennsylvania, on the even starting for New York, falls asleep while awaiting the steam-boat. He dreams that upon his awakening, Time and the world have made an advance of three hundred years―that he is informed of this fact by two persons who afterwards prove to be his immediate descendents in the eighth generation. They tell him that, while taking his nap, he was buried, together with the house in which he sat, beneath an avalanche of snow and earth precipitated from a neighboring hill by the discharge of the signal-gun―that the tradition of the event had been preserved, although the spot of his disaster was at that time overgrown with immense forest trees―and that his discovery was brought about by the neccesity for opening road through the hill. He is astonished, as well he may be, but, taking courage, travels through the country between Philadelphia and New York, and comments upon its alterations. These latter are, for the most part, well conceived―some are sufficiently outré. Returning from his journey he stops at the scene of his original disaster and is seated, once more, in the disentombed house, while awaiting a companion. In the meantime he is awakened―finds he has been dreaming―that the boat has left him―but also (upon receipt of a letter) that there is no longer any necessity for his journey. The [The] Little Couple, and The Thread and Needle Store are skilfully told, and have much spirit and freshness.

///////////////////////////////////////

[Mary Griffith.] Camperdown; or, News from Our Neighbourhood―Being a Series of Sketches, by the author of "Our Neighborhood," &c. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea & Blanchard. E-text at Internet Archive [University of California Libraries; MSN] <http://www.archive.org/stream/camperdownornews00grifrich#page/n9/mode/2up>

"Mary Griffith," Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Griffith>

ポーが書評した本 (2) S・アンナ・ルイスの『海の子、その他の詩』 (1848) [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

Edgar Allan Poe, Review of The Child of the Sea and other Poems, from Southern Literary Messenger, September 1848, pp. 569-571 [E-text @E. A. Poe Society of Baltimore <http://www.eapoe.org/works/criticsm/slm48l01.htm>

"MRS. LEWIS' POEMS.*"

* The Child of the Sea and other Poems. By S. Anna Lewis, author of "Records of the Heart," etc., etc.

ルイス夫人の詩〔S・アンナ・ルイス著『海の子、その他の詩』〕

というのが『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』誌の1848年7月号に掲載されたポーの書評のタイトル。だけど、ほんとうは "The"はない。

Child of the Sea and Other Poems. By Mrs. S. Anna Lewis, author of "Records of the Heart," etc., etc. New York: George P. Putnam, 1848.

16篇からなる詩集――(1) "Child of the Sea"―(2) "Isabelle; or The Broken Heart: A Tale of Hispaniola"―[Miscellaneous Poems:] (3) "Una"―(4) "The Unmasked"―(5) "Death of Osceola"―(6) "The Beleaguerred Heart"―(7) "My Study"―(8) "Heart Joys"―(9) "The Poet"―(10) "Poesy"―(11) "To Corinne"―(12) "Lament of la Vega"―(13) "The Dead"―(14) "The Angels: An Impromptu"―(15) "The Bard"―(16) "Wreck of the Cutter"

180ページほどの本の、最初の2作が長詩(物語詩)で、それぞれ90ページ、45ページくらい占めています。

E-text at Internet Archive [Library of Congress; Sloan Foundation] <http://www.archive.org/details/childofsea00lewi>

アメリカの女性詩人セーラ・アンナ・ルイス Sarah Anna Lewis, 1824-80 (このひとはファーストネームに自由な発想をもっていて、Estelle Anna と名乗ったり、Stella と名乗ったり、 夫と離別後に渡欧してヨーロッパで客死したときには Estelle Delmonte Lewis だった)は、ポーと同時期にフォーダムに在住していたアマチュア詩人で、1847年1月末にポーの妻のヴァージニアが亡くなったあと、(とくにポー不在中に)義母のクレム夫人の世話をし、経済的な援助もしてくれたのでした。

.jpg)

image via Internet Archive (E-text from Library of Congress; Sloan Foundation <http://www.archive.org/details/childofsea00lewi> エス S をけしてエステルEstelle とえんぴつがきされている)

ニューヨーク州Troy の学生時代に処女詩集 Records of the Heart を刊行し、ヴァージルをギリシア語から英語に韻文訳するみたいなこともやっている、才女でした。1841年弁護士のSydney Lewis と結婚してブルックリンに転居、文学サロンみたいなものを開いて、ニューヨーク市の文学シーンでちょっと脚光を浴びたみたいです(金持ちだったんでしょうね)。

新しい詩集が出たときに、ポーに好意的な書評を書いてくれるように、100ドルが渡った(彼女からというよりたぶん旦那のシドニー)とされていて、お手盛り的・ヨイショ的な批評となっていると言われています(「この詩集を20回読んだ」とか書かれていて、ヤレヤレと思います)。ポーは旦那の申し出を断った(死んでも書けないとかなんとか言って)ともされていて、よくわからんですが、当該のことだけでなくて、かねて経済的な援助を受け、彼女の詩の添削みたいなことも行なっていたとも言われています。

Evert and George Duyckinck, ed., Cyclopaedia; image via "Estelle Anna Lewis (1824-1880)," Portraits of American Women Writers <http://www.librarycompany.org/women/portraits/lewis.htm>

ポーがルイスの詩を褒めたのは、妻ヴァージニアの死後にルイスから与えられた経済的・心情的援助に報いるポーなりのやりかただったと考えられているわけです。「評論家の意見は一致して、彼女をこの国の女性詩人の最高のランクではないにしても高いランクに位置づけることに合意するだろう」というのがポーの評言です。

image via Baltimore Poe Society <http://www.eapoe.org/people/lewissa.htm>

ルイスは凡庸な詩人と考えられていますけれど、ヨーロッパで発表した詩劇 Sappho of Lesbos (1868年ロンドン初演)はたいへんなヒットとなるわけで、そんなに凡庸な人ではないのかもしれない。読んで考えてみたいと思います。パラパラ見るところ、錬金術とか超自然とか、ポーとつながるところがあるような気もしなくもないです。

とくにヴァージニアの死後のポー宅にルイス夫人がよく顔を出していて、ポーは顔を合わせたくないみたいなときもあったことがクレム夫人(義母)の回想に記録されています。ポー最晩年の詩「アナベル・リー」のモデルはわたしよ♪、と複数の女性が手を挙げたわけですが、アンナ・ルイスもそのひとりでした。

////////////////////////////////////

Lewis, Mrs. S. Anna Lewis. Child of the Sea and Other Poems. New York: George P. Putnam, 1848. E-text at Internet Archive [Library of Congress; Sloan Foundation] <http://www.archive.org/details/childofsea00lewi>

"Estelle Anna Lewis (1824-1880)," Portraits of American Women Writers <http://www.librarycompany.org/women/portraits/lewis.htm>

"Mrs. Sarah Anna Lewis," Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore <http://www.eapoe.org/people/lewissa.htm>

Edgar Allan Poe, Review of The Child of the Sea and other Poems, from Southern Literary Messenger, September 1848, pp. 569-571 [E-text @E. A. Poe Society of Baltimore <http://www.eapoe.org/works/criticsm/slm48l01.htm>

///////////////////////////////////////

"Stella," Sappho, 2nd ed. (London, 1876) <http://www.archive.org/details/sapphoatragedyi00lewigoog>

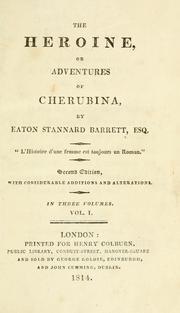

ポーが書評した本 (3) イートン・スタナード・バレットの『ヒロイン』 ([1813;] 1814; rpt.1835?) Books Reviewed by Poe (3): _The Heroine; or, The Adventures of Cherubina_ by Eaton Stannard Barrett [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

The Heroine: or Adventures of Cherubina. By Eaton Stannard Barrett, Esq. New Edition. Richmond: Published by P. D. Bernard.

『ヒロイン――あるいは、チェラビーナの冒険』 イートン・スタナード・バレット著. 新版. リッチモンド: P・D・バーナード刊.

E-text @Internet Archive

a) The Heroine, or Adventures of a Fair Romance Reader. By Eaton Stannard Barrett, Esq. In Three Volumes. London: Henry Colburn, 1813. Vol. 1: 298pp. E-text @Internet Archive (Library of the University of California; ) <http://www.archive.org/stream/heroinebyeatonst00barrrich#page/n19/mode/2up>.jpg)

b) The Heroine, or Adventures of Cherubina, by Eaton Stannard Barrett, Esq. Second Edition, with Considerable Additions and Alterations. In Three Volumes. London: Henry Colburn, 1814. Vol. 1: 235pp. <http://www.archive.org/stream/heroineoradventu01barre#page/234/mode/2up>

vol.2.jpg)

c) The Heroine, or Adventures of Cherubina,by Eaton Stannard Barrett, Esq. Third Edition. In Three Volumes. London: Henry Colburn, 1815. Vol. 1: 220pp. (with a 6-page notes); vol. 2: 240pp. (10p. notes); vol. 3: 252pp. (6p. notes). E-text @Internet Archive (New York Public Library; Google) <http://www.archive.org/stream/heroineoradvent02barrgoog#page/n4/mode/2up> 〔e-text は3巻を合冊。注付きの1815年版。ただし読めないページあり〕.jpg)

d) The Heroine, by Eaton Stannard Barrett. With an Introduction by Walter Raleigh. London: Henry Frowde, 1909. xv, 298pp. E-text @Internet Archive (California University Libraries; MSN) <http://www.archive.org/stream/heroinebyeatonst00barrrich#page/n3/mode/2up> 〔ウォルター・ローリー(オックスフォード大学英文科教授だったひと (1861-1922) で、エリザベス女王の寵臣とは別人)による序文を付す〕.jpg)

アイルランドの作家イートン・スタナード・バレット Eaton Stannard Barrett, 1786-1820のゴシック諷刺小説『ヒロイン』 (1814) の書評は『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』誌の1835年12月号に発表されました。

バレットについては、日本語ウィキペディアに記事はなく、英語も短い記事です。――

Eaton Stannard Barrett (1786 – March 20, 1820) was an Irish poet and author.

Career

Born in County Cork, Barrett studied law at Middle Temple, London. He is best known for his satirical poems about British political figures. The lines on the headstone of Thomas Moore’s daughter, usually ascribed to Joseph Atkinson, are actually by Barrett.[1] He died in Wales of tuberculosis in 1820. His brother, Richard Barrett, editor of The Dublin Pilot, was a fellow-prisoner of Daniel O'Connell, and died at Dalkey about 1855.[2]

アイルランド生まれの詩人・作家で、英国の政治家についての諷刺詩で知られる、ということ以外は、瑣末なことしか書かれていません。

ポーがアメリカにおける第一人者と考えられてきたゴシック小説については、『カリフォルニア時間』でむかしあれこれ書きました――「January 2-3 ゴシック小説と合理主義(その2)――擬似科学をめぐって(6) On Pseudosciences (6) [短期集中 擬似科学 Pseudoscience]」など。

諷刺ゴシックについては、ジェーン・オースティンの『ノーサンガー・アビー』(1818)が有名ですけど、もともと人工的(つまり私的現実から素材が得られるというよりも過去の文書・作品から材料は得られる)かつ(超自然については)近代的懐疑的姿勢を内包していたゴシックというジャンルを、オースティンみたいなアイロニーや機知に富んだひと、あるいは諷刺的なひとが扱えば、おのずと恐怖と笑いは錯綜します(オースティンの小説は刊行は遅れに遅れますけど、執筆は1790年ごろだったかするはずで、既に諷刺やパロディーはアン・ラドクリフの流行と並行して起こっていました)し、本(小説)についての本(小説)とか、語ることについて語るとか、いわばメタ・フィクショナルなまなざしがあらわれがちでしょう。ゴシックのパロディーがゴシックの新型になって発展するという事態は、既にポーの時代には「支流」「傍流」ゴシックとしては強い流れになっています。ポー自身がユーモアとは言えずとも笑いや機智やアイロニーを好んだひとでしたから、バレットの本に大いに反応するのは当然かもしれず、また、興味深いことです。

冒頭はトンコ法でチェラビーナに呼びかけちゃっています。必読の書であり、すべての整備された書棚に置かれてしかるべき本である。とりわけバレットのウィットに富んだ皮肉、あるいは皮肉に富んだウィットを評価して、また、文体は無比無類、追随許さずまねできない positively inimitable とほめます。

ま、作品をちゃんと読んでから考えてみます。

それにしても、予定の紙幅を超過しているけれども、ぜひ25章を読んでいただきたい、とか言って、後半の大半を長~い引用で埋めているのには、呆れます。いまだったら編集者も教師もダメ出しをするで笑。

///////////////////////////////

"Eaton Stannard Barret," Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eaton_Stannard_Barrett>

"Eaton Stannard Barrett," Library Ireland <http://www.libraryireland.com/biography/EatonStannardBarrett.php> 〔From A Compendium of Irish Biography, 1878〕

"Online Books by Eaton Stannard Barrett," Online Books Page <http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Barrett%2C%20Eaton%20Stannard%2C%201786-1820>

☆ ☆ ☆ ☆ ☆

The Heroine: or Adventures of Cherubina. By Eaton Stannard Barrett, Esq. New Edition. Richmond: Published by P. D. Bernard.CHERUBINA! Who has not heard of Cherubina? Who has not heard of that most spiritual, that most ill-treated, that most accomplished of women―of that most consummate, most sublimated, most fantastic, most unappreciated, and most inappreciable of heroines? Exquisite and delicate creation of a mind overflowing with fun, frolic, farce, wit, humor, song, sentiment, and sense, what mortal is there so dead to every thing graceful and glorious as not to have devoured thy adventures? Who is there so unfortunate as not to have taken thee by the hand?―who so lost as not to have cultivated thy acquaintance?―who so stupid, as not to have enjoyed thy companionship?―who so much of a log, as not to have laughed until he has wept for very laughter in the perusal of thine incomparable, inimitable, and inestimable eccentricities? But we are becoming pathetic to no purpose, and supererogatively oratorical. Every body has read Cherubina. There is no one so superlatively un happy as not to have done this thing. But if such there be―if by any possibility such person should exist, we have only a few words to say to him. Go, silly man, and purchase forthwith “The Heroine: or Adventures of Cherubina.”

The Heroine was first published many years-ago, (we believe shortly after the appearance of Childe Harold;) but although it has run through editions innumerable, and has been universally read and admired by all possessing talent or taste, it has never, in our opinion, attracted half that notice on the part of the critical press, which is undoubtedly its due. There are few books written with more tact, spirit, näiveté, or grace, few which take hold more irresistibly upon the attention of the reader, and none more fairly entitled to rank among the classics of English literature than the Heroine of Eaton Stannard Barrett. When we say all this of a book possessing not even the remotest claim to originality, either in conception or execution, it may reasonably be supposed, that we have discovered in its matter, or manner, some rare qualities, inducing us to hazard an assertion of so bold a nature. This is actually the case. Never was any thing so charmingly written: the mere style is positively inimitable. Imagination, too, of the most etherial kind, sparkles and blazes, now sportively like the Will O’ the Wisp, now dazzlingly like the Aurora Borealis, over every page―over every sentence in the book. It is absolutely radiant with fancy, and that of a nature the most captivating, although, at the same time, the most airy, the most capricious, and the most intangible. Yet the Heroine must be considered a mere burlesque; and, being a copy from Don Quixotte, is to that immortal work of Cervantes what The School for Scandal is to The Merry Wives of Windsor. The Plot is briefly as follows.

Gregory Wilkinson, an English farmer worth 50,000 pounds, has a pretty daughter called Cherry, whose head is somewhat disordered from romance reading. Her governess is but little more rational than herself, and is one day turned out of the house for allowing certain undue liberties on the part of the butler. In revenge she commences a correspondence with Miss Cherry, in which she persuades that young lady that Wilkinson is not her real father―that she is a child of mystery, &c.―in short that she is actually and bona fide a heroine. In the meantime, Miss Cherry, in rummaging among her father’s papers, comes across an antique parchment-a lease of lives-on which the following words are alone legible.This Indenture

For and in consideration of

Doth grant, bargain, release

Possession, and to his heirs and assigns

Lands of Sylvan Lodge, in the

Trees, stones, quarries, &c.

Reasonable amends and satisfaction

This demise

Molestation of him the said Gregory Wilkinson.

The natural life of

Cherry Wilkinson only daughter of

De Willoughby eldest son of Thomas

Lady Gwyn of Gwyn Castle.

This “excruciating MS.” brings matters to a crisis―for Miss Cherry has no difficulty in filling up the blanks.“It is a written covenant,” says this interesting young lady in a letter to her Governess, “between this Gregory Wilkinson, and the miscreant (whom my being an heiress had prevented from enjoying the title and estate that would devolve to him at my death) stipulating to give Wilklinson ‘Sylvan Lodge,’ together with ‘trees, stones, &e.’ as ‘reasonable amends and satisfaction’ for being the instrument of my ‘demise,’ and declaring that there shall be ‘no molestation of him the said Gregory Wilkinson’ for taking away the ‘natural life of Cherry Wilkinson, only daughter of’― somebody ‘De Willoughby eldest son of Thomas.’ Then follows ‘Lady Gwyn of Gwyn Castle.’ So that it is evident I am a De Willoughby, and related to Lady Gwyn! What perfectly confirms me in the latter supposition, is an old portrait which I found soon after, among Wilkinson’s papers, representing a young and beautiful female superbly dressed; and underneath, in large letters, the name of ‘Nell Gwyn.’”

Fired with this idea, Miss Cherry gets up a scene, rushes with hair dishevelled into the presence of the good man Wilkinson, and accuses him to his teeth of plotting against her life, and of sundry other mal-practices and misdemeanors. The worthy old gentleman is astonished, as well he may be; but is somewhat consoled upon receiving a letter from his nephew, Robert Stuart, announcing his intention of paying the family a visit immediately. Wilkinson is in hopes that a lover may change the current of his daughter’s ideas; but in that he is mistaken. Stuart has the misfortune of being merely a rich man, a handsome man, an honest man, and a fashionable man-he is no hero. This is not to be borne: and Miss Cherry, having assumed the name of the Lady Cherubina De Willoughby, makes a precipitate retreat from the house, and commences a journey on foot to London. Her adventures here properly begin, and are laughable in the extreme. But we must not be too minute. They are modelled very much after those of Don Quixotte, and are related in a series of letters from the young lady herself to her governess. The principal characters who figure in the Memoirs are Betterton, an old debauché who endeavors to entangle the Lady Cherubina in his toils―Jerry Sullivan, an Irish simpleton, who is ready to lose his life at any moment for her ladyship, whose story he implicitly believes, without exactly comprehending it―Higginson, a grown baby, and a mad poet―Lady Gwyn, whom Cherubina believes to be her mortal enemy, and the usurper of her rights, and who encourages the delusion for the purpose of entertaining her guests―Mary and William, two peasants betrothed, but whom Cherry sets by the ears for the sake of an interesting episode―Abraham Grundy, a tenth rate performer at Covent Garden, who having been mistaken by Cherry for an earl, supports the character à merveille with the hope of eventually marrying her, and thus securing 10,000 pounds, a sum which it appears the lady possesses in her own right. He calls himself the Lord Altamont Mortimer Montmorenci. Stuart, her cousin, whom we have mentioned before, finally rescues her from the toils of Betterton and Grundy, and restores her to reason, and to her friends. Of course he is rewarded with her hand.

We repeat that Cherubina is a book which should be upon the shelves of every well-appointed library. No one can read it without entertaining a high opinion of the varied and brilliant talents of its author. No one can read it without laughter. Its wit, especially, and its humor, are indisputable―not frittered and refined away into that insipid compound which we occasionally meet with, half giggle and half sentiment―but racy, dashing, and palpable. Some of the songs with which the work is interspersed have attained a most extensive popularity, while many persons, to whom they are as familiar as household things, are not aware of the very existence of the Heroine. All our readers must remember the following.

Dear Sensibility, O la!

I heard a little lamb cry ba!

Says I, so you have lost mamma!

Ah!

The little lamb as I said so,

Frisking about the fields did go,

And frisking trod upon my toe.

Oh!And this also.

TO DOROTHY PULVERTAFT.

If Black-sea, White-sea, Red-sea ran

One tide of ink to Ispahan;

If all the geese in Lincoln fens

Produced spontaneous well-made pens;

If Holland old or Holland new,

One wondrous sheet of paper grew;

Could I, by stenographic power,

Write twenty libraries an hour;

And should I sing but half the grace

Of half a freckle on thy face;

Each syllable I wrote should reach

From Inverness to Bognor’s beach;

Each hair-stroke be a river Rhine,

Each verse an equinoctial line.We have already exceeded our limits, but cannot refrain from extracting Chapter XXV. It will convey some idea of the character of the Heroine. She is now at the mansion of Lady Gwyn, who, for the purpose of amusing her friends, has dressed up her nephew to represent the supposed mother of the Lady Cherubina.

CHAPTER XXV.

This morning I awoke almost well, and towards evening was able to appear below. Lady Gwyn had invited several of her friends; so that I passed a delightful afternoon; the charm, admiration, and astonishment of all.

When I retired to rest, I found this note on my toilette. To the Lady Cherubina.Your mother lives! and is confined in a subterranean vault of the villa. At midnight two men will tap at your door, and conduct you to her. Be silent, courageous, and circumspect. What a flood of new feelings gushed upon my soul, as I laid down the billet, and lifted my filial eyes to Heaven! Mother―endearing name! I pictured that unfortunate lady stretched on a mattress of straw, her eyes sunken in their sockets, yet retaining a portion of their youthful fire; her frame emaciated, her voice feeble, her hand damp and chill. Fondly did I depict our meeting―our embrace; she gently pushing me from her, and baring my forehead, to gaze on the lineaments of my countenance. All, all is convincing; and she calls me the softened image of my noble father!

Two tedious hours I waited in extreme anxiety. At length the clock struck twelve; my heart beat responsive, and immediately the promised signal was made. I unbolted the door, and beheld two men masked I and cloaked. They blindfolded me, and each taking an arm, led me along. Not a word passed. We traversed apartments, ascended, descended stairs; now went this way, now that; obliquely, circularly, angularly; till I began to imagine we were all the time in one spot.

At length my conductors stopped.

‘Unlock the postern gate,’ whispered one, ‘while I light a torch.’

‘We are betrayed!’ said the other, ‘for this is the wrong key.’

‘Then thou beest the traitor,’ cried the first.

‘Thou liest, dost lie, and art lying!’ cried the second.

‘Take that!’ exclaimed the first. A groan followed, and the wretch tumbled to the ground.

‘You have killed him!’ cried I, sickening with horror.

‘I have only hamstrung him, my Lady,’ said the fellow. ‘He will be lame while ever he lives; but by St. Cripplegate, that won’t be long; for our captain has given him four ducats to murder himself in a month.’

He then burst open the gate; a sudden current of wind met us, and we hurried forward with incredible speed, while moans and smothered shrieks were heard at either side.

‘Gracious goodness, where are we?’ cried I.

‘In the cavern of death!’ said my conductor; ‘but never fear, Signora mia illustrissima, for the bravo Abellino is your povero devotissimo.’

On a sudden innumerable footsteps sounded behind us. We ran swifter.

‘Fire!’ cried a ferocious accent, almost at my ear; and there came a discharge of arms.

I stopped, unable to move, breathe, or speak.

‘I am wounded all over, right and left, fore and aft, long ways and cross ways, Death and the Devil!’ cried the bravo.

‘Am I bleeding?’ said I, feeling myself with my hands.

‘No, blessed St. Fidget be praised!’ answered he; ‘and now all is safe, for the banditti have turned into the wrong passage.’

He then stopped, and unlocked a door.

‘Enter,’ said he, ‘and behold your mother!’

He led me forward, tore the bandage from my eyes, and retiring, locked the door after him.

Agitated by the terrors of my dangerous expedition, I felt additional horror in finding myself within a dismal cell, lighted with a lantern; where, at a small table, sat a woman suffering under a corpulency unparalleled in the memoirs of human monsters. Her dress was a patchwork of blankets and satins, and her gray tresses were like horses’ tails. Hundreds of frogs leaped about the floor; a piece of mouldy bread, and a mug of water, lay on the table; some straw, strewn with dead snakes and sculls, occupied one corner, and the distant end of the cell was concealed behind a black curtain.

I stood at the door, doubtful, and afraid to advance; while the prodigious prisoner sat examining me all over.

At last I summoned courage to say, ‘I fear, madam, I am an intruder here. I have certainly been shown into the wrong room.’

‘It is, it is my own, my only daughter, my Cherubina!’ cried she, with a tremendous voice. ‘Come to my maternal arms, thou living picture of the departed Theodore!’

‘Why, ma’am,’ said I, ‘I would with great pleasure, but I am afraid―Oh, madam, indeed, indeed, I am quite sure you cannot be my mother!’

‘Why not, thou unnatural girl?’ cried she.

‘Because, madam,’ answered I, ‘my mother was of a thin habit, as her portrait proves.’

‘And so I was once,’ said she. ‘This deplorable plumpness is owing to want of exercise. But I thank the Gods 1 am as pale as ever.’

‘Heavens! no,’ cried I. ‘Your face, pardon me, is a rich scarlet.’

‘And is this our tender meeting?’ cried she. ‘To disown me, to throw my fat in my teeth, to violate the lilies of my skin with a dash of scarlet? Hey diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle! Tell me, girl, will you embrace me, or will you not?’

‘Indeed, madam,’ answered I, ‘I will presently.’

‘Presently!’

‘Yes, depend upon it I will. Only let me get over the first shock.’

‘Shock!’

Dreading her violence, and feeling myself bound to do the du ties of a daughter, I kneeled at her feet, and said:

‘Ever respected, ever venerable author of my being, I beg thy maternal blessing!’

My mother raised me from the ground, and hugged me to her heart, with such cruel vigor, that, almost crushed, I cried out stoutly, and struggled for release.

‘And now,’ said she, relaxing her grasp, ‘let me tell you of my sufferings. Ten long years I have eaten nothing but bread. Oh, ye favorite pullets, oh, ye inimitable tit-bits, shall I never, never taste you more? It was but last night, that maddened by hunger, methought I beheld the Genius of Dinner in my dreams. His mantle was laced with silver eels, and his locks were drop ping with soups. He had a crown of golden fishes upon his head, and pheasants’ wings at his shoulders. A flight of little tartlets fluttered about him, and the sky rained down comfits. As I gazed on him, he vanished in a sigh, that was impregnated with the fumes of brandy. Hey diddle diddle, the cat and the fiddle.’

I stood shuddering, and hating her more and more every moment.

‘Pretty companion of my confinement!’ cried she, apostrophizing an enormous toad which she pulled out of her bosom ‘dear, spotted fondling, thou, next to my Cherubina, art worthy of my love. Embrace each other, my friends.’ And she put the hideous pet into my hand. I screamed and dropped it.

‘Oh!’ cried I, in a passion of despair, ‘what madness possessed me to undertake this execrable enterprise!’ and I began beating with my hand against the door.

‘Do you want to leave your poor mother?’ said she in a whimpering tone.

‘Oh! I am so frightened!’ cried I.

‘You will spend the night here, however,’ said she; ‘and your whole life too; for the ruffian who brought you hither was employed by Lady Gwyn to entrap you.’

When I heard this terrible sentence, my blood ran cold, and I began crying bitterly.

‘Come, my love!’ said my mother, ‘and let me clasp thee to my heart once more!’

‘For goodness sake!’ cried I, ‘spare me!’

‘What!’ exclaimed she, ‘do you spurn my proffered embrace again?’

‘Dear, no, madam,’ answered I. ‘But―but indeed now, you squeeze one so!’

My mother made a huge stride towards me; then stood groaning and rolling her eyes.

‘Help!’ cried I, half frantic, ‘help! help!’

I was stopped by a suppressed titter of infernal laughter, as if from many demons; and on looking towards the black curtain, whence the sound came, I saw it agitated; while about twenty terrific faces appeared peeping through slits in it, and making grins of a most diabolical nature. I hid my face with my hands.

‘ ’Tis the banditti!’ cried my mother.

As she spoke, the door opened, a bandage was flung over my eyes, and I was borne away half senseless, in some one's arms; till at length, I found myself alone in my own chamber. Such was the detestable adventure of to-night. Oh, that I should live to meet this mother of mine! How different from the mothers that other heroines rummage out in northern turrets and ruined chapels! I am out of all patience. Liberate her I must, of course, and make a suitable provision for her too, when I get my property; but positively, never will I sleep under the same roof with―(ye powers of filial love forgive me!) such a living mountain of human horror. Adieu.

ポーが書評した本 (4) 『テキサスの歴史』 (1836) Books Reviewed by Poe (4): _The History of Texas_ by David E. Edward [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

ポーは文学書だけじゃなくていろんな本の書評を書きました。

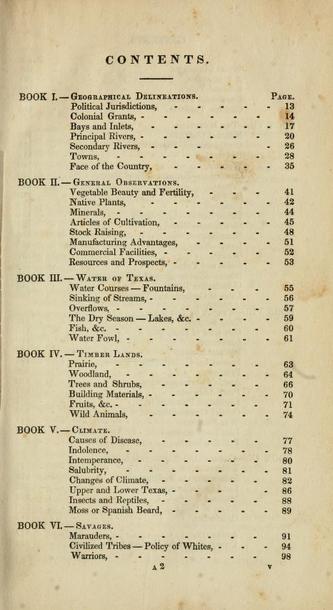

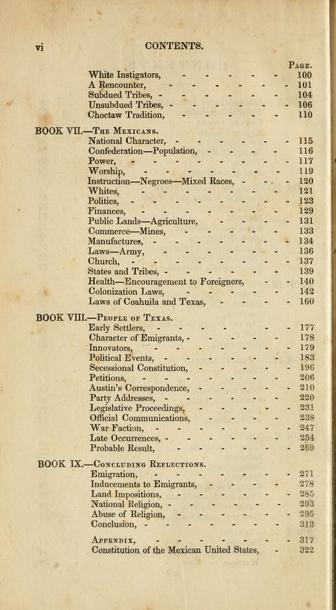

The History of Texas: or the Emigrant's, Farmer's, and Politician's Guide to the Character, Climate, Soil, and Productions of that Country; Geographically Arranged from Personal Observation and Experience. By David B. Edward, formerly Principal of the Academy, Alexandria, Lousiana; Late Preceptor of Gonzales Seminary, Texas. Cincinnati: J. A. James & Co.[, 1836]

デイヴィッド・B・エドワード著 『テキサスの歴史――または、この国〔地域〕 (Country) の特性、気候、土壌、そして産物についての、移民の、農民の、そして政治家の案内書――個人的観察と体験により地理学的に構成』 シンシナチ:J・A・ジェイムズ, 1836. 336pp.

E-text @Internet Archive: The Library of Congress; Sloan Foundation <http://www.archive.org/stream/historyoftexas01edwa#page/n5/mode/2up>

『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』誌の1836年8月号に掲載された書評。ポウはこの本を「有用な珍本 useful odditties」に入ると冒頭で位置づけ、「テキサスに関してわずかの量しかない我々の精確な知識に対して貴重な付与となるもの」と言っています。

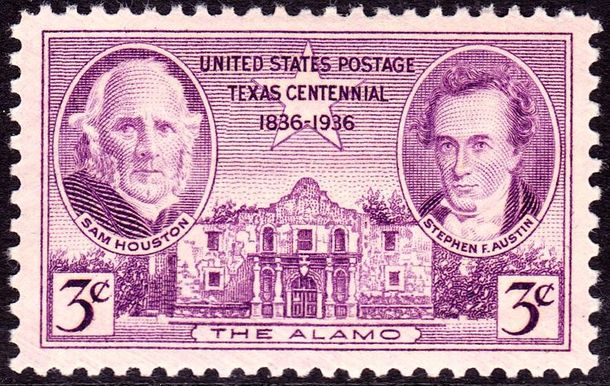

テキサスがアメリカ合衆国の28番目の州になるのは1845年12月29日のことです。1836年までメキシコの一部(その前は1821年にメキシコが独立するまではスペイン領)であったのが、独立を宣言して共和国 republic になったのでした。

日付を並べると、第二次アナウアク騒擾事件1835年6月――テキサス独立戦争開始 1835年10月1or2日――「アラモの戦い」1836年2月23日~3月6日――独立宣言1836年3月2日――「サンジャシントの戦い」=テキサス独立戦争(テキサス革命)の終結1836年4月21日――ベラスコ条約1836年5月14日――

独立を宣言したのは、アメリカからの入植者たちです(初代大統領は独立戦争において最高司令官であったサミュエル・ヒューストン)。入植を父の代から数十年にわたってすすめ「テキサスの父」と呼ばれるのがスティーヴン・オースティン (1793-1836) です。

アラモの戦い100周年記念切手(1936) image via Wikipedia, Wikimedia Commons: from "Stephen Austin" <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_F._Austin>

どちらもポーと同じヴァージニア出身でした。オースティンはフリーメーソンで、テキサス独立アメリカ陰謀説とつながっていたりします。

ポーが書評のなかで使っている "savages" (野蛮人)ということばは原書にあるのをそのまま引いているのですけど (Book VI―SAVAGES)、もっぱらインディアンのことかと思ったら、白人の扇動者とか掠奪者も入っている。

この本は、いつごろ書かれたのか、ちゃんと読んでみないとわかりませんけれど、付録にはメキシコ合衆国の憲法が載っていますので、独立前の様子ということになるのでしょうか。ともあれ、ポーの書評が載った1836年夏の時点で、話題の地域であったのは確かです。

南部・黒人問題について書いておくと、メキシコ政府下では黒人奴隷は解放されていたのが、テキサス独立によって奴隷制が復活します。また、アメリカとメキシコとの対立はその後さらにカリフォルニアやニュー・メキシコをめぐって米墨戦争 (1846-48) へ突入し、その後のゴールド・ラッシュに伴う白人・黒人問題、自由州・奴隷州の論争を経て、米国内では南北戦争による奴隷制の決着という未曾有の「内戦 Civil War」へとつながっていくのでした。

HISTORY OF TEXAS.

The History of Texas: or the Emigrant's, Farmer's, and Politician's Guide to the Character, Climate, Soil, and Productions of that Country; Geographically Arranged from Personal Observation and Experience. By David B. Edward, formerly Principal of the Academy, Alexandria, Lousiana; Late Preceptor of Gonzales Seminary, Texas. Cincinnati: J. A. James & Co.

This should be classed among useful oddities. Its style is somewhat over-abundant―but we believe the book a valuable addition to our very small amount of accurate knowledge in regard to Texas. The author, who is one of the Society of Friends 〔Quaker の公式名称〕, assures us that he has no lands in Texas to sell, although he has lived three years in the country, and that, too, on the frontiers―that he made one of a party of four who explored the province in 1830, from side to side, and from settlement to settlement, during the space of six months more in examining the improvements made throughout every locality, "in order that none should be able to detect a falsehood, or prove a material error which could either mislead, or seriously injure those who may put confidence in this work." For ourselves we are inclined to place great faith in the statements of Mr. Edward, and regard his book with a most favorable eye. It is an octavo of 336 pages, embracing, in detail, highly interesting accounts of the People, the Geographical Features, the Climate, the Savages, the Timber, the Water, &c. of Texas. Much information in regard to Mexico, is included in the body of the work, and, in an Appendix, we have a copy of the Mexican Constitution. We give, by way of extract, a flattering little picture of Texian comfort and abundance.

The people en masse can have a living, and that plentifully too, of animal food, both of beef and pork, of venison and bear meal, besides a variety of fish and fowl, upon easier terms at present, especially the wild game, than any other people, in any other district of North America; which must continue to be the case, for one of the best reasons in the world―at least in Texas: as the wild animals decrease, the domesticated ones will increase.

And, as they have not commenced, except in a few cases (comparatively speaking) upon the border lands of the Gulf, to export corn, they have by just dropping the seed and afterwards stowing away the increase, more bread stuff than they well know sometimes what to do with, it being out of the question to feed their hogs on it, except they were to raise them on such food together, which would be a pity, while they have so much mast in the woods, and so many roots in the prairies.

And, as their milch 〔milkを出すの意味の形容詞〕 cattle increase in numbers, and that very frequently too faster than they can attend to their milking, they have more, as to family use, much more milk, than they know how to dispose of, except they are well stocked with farrow sows, or have around them pet mustang colts.

With these three main stays of a farmer's life, come, by very little more exertion than just the picking and gathering in, those condiments and relishes, which not [column 2] only garnish the table, but replenish the appetite, from a source of such plentiful variegation, as the gardens and the fields, the woods and the waters, of a Texas country!

目次

ポーが書評した本 (5) 『馬を探す紳士の冒険』 (1835; 1836) Books Reviewed by Poe (5): _Adventures of a Gentleman in Search of a Horse_ by Caveat Emptor, Gent. [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

ポーは文学書だけじゃなくていろんな本の書評を書きました。

ADVENTURES IN SEARCH OF A HORSE.

The Adventures of a Gentleman in Search of a Horse. By Caveat Emptor, Gent. One, Etc. Philadelphia: Republished by Cary, Lea and Blanchard[, 1836].

キャヴィート・エンプター著 『馬を探す紳士の冒険』 フィラデルフィア:ケアリー・リー・アンド・ブランシャード再刊, 1836. 288pp.

E-text @Internet Archive: The Library of Congress; Google <http://www.archive.org/stream/adventuresagent04stepgoog#page/n9/mode/2up>

ポーは、この本は実用的なところはもちろんだけれど、文学的に特異 (remarkable as being an anomaly in the literary way) と書き、はじめの180ページはタイトルが示すように一頭の馬を探す紳士の冒険を語り、残りの100ページは英国における馬の取引きの法律を語る、と説明しています。

調べてみると原著は、ロンドンで前年の1835年に出版されています。――

London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green, & Longman, and Samuel Bagster, 1835. xi, 336pp.

E-text @Internet Archive: Oxford University; Google <http://www.archive.org/stream/adventuresagent00stegoog#page/n6/mode/2up>

これでわかるのは、第一に、初版のイギリス版をポーは参照しないで、ページ数をあくまでアメリカ版で了解していること、第二に、翻訳じゃないし、かつ海賊版が横行していた時代だったから、容易だったとはいえ、1年後にはアメリカ版が出版され、その書評が書かれていること、です。

ポーが目利きだったという話ではなくて、イギリスで出た本がよく読まれる/読まれそうだと、アメリカでも出版された、という話です。

この本はイギリスでは1837年には4版まで重ねています。――

London: Saunders and Otley, 1837. xxxv, 392pp.

E-text @Internet Archive: Oxford University; Google <http://www.archive.org/stream/adventuresofgent1837step#page/n5/mode/2up>

初版の出版社とは異なります。版権(著作権)はどうなっていたのやら。

冒頭に、文学書以外にも、と書きましたけれど、ポーのまなざしは、第一部の物語(と呼べないのならニュージャーナリズム的ルポルタージュかしら)と、それを含めての作品構成にあるようです。

ポー百科事典は、「『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』の1836年8月号掲載の、馬売買についての本の書評。「すべての素人愛好者はキャヴィート・エンプターの本をすべからくよく見るべし、そく見るべし」と薦めている。」と記すのみ。Sova というひとの同種の本 (Critical Companion to Edgar Allan Poe: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work) は、ポー百科を冒頭でなぞってから、"Caveat Emptor" の名前がラテン語で、英語に直すと "let the buyer beware" (買い主に注意させよ)の意味であり、本書が馬購入における法律的側面の案内書であることを説明しています。あとは上に書いたような構成と、ポーが「すべてのアマチュア all amateurs」に本書を推薦していることが述べられています。

ポーが何をおもしろがっているのか、おもしろがって薦めているのか、ちょっとストレートじゃないのかもしれない。まー、作品をひまなときに読んでみないとわかりませんけど。

ポーが、とても笑える木版画と記しているたくさんの挿絵のなかから――"illustrated by very laughable wood-cuts"――どこがおかしいんだろう、と思いながらも、ポーと笑いを共有していると思うとそれ自体おかしいw

ADVENTURES IN SEARCH OF A HORSE.

The Adventures of a Gentleman in Search of a Horse. By Caveat Emptor, Gent. One, Etc. Philadelphia: Republished by Cary, Lea and Blanchard.

This book, to say nothing of its peculiar excellence and general usefulness, is remarkable as being an anomaly in the literary way. The first 180 pages are occupied with what the title implies, the adventures of a gentleman in search of a horse―the remaining 100 embrace, in all its details, difficulties, and intricacies, a profound treatise on the English laws of horse-dealing warranty!―and this too, strange as it may seem, appears to be the first and only treatise upon a subject so interesting to a great portion of the English gentry. Think of law, serviceable law too, intended as a matter of reference, compiled by a well known attorney, and dedicated to Sir John Gurney, one of the Barons of his Majesty's Court of Exchequer―think of all this done up in a green muslin cover, and illustrated by very laughable wood-cuts. Only imagine the stare of old Coke, and of the other big wigged tribe in white calf and red-letter binding, as our friend in the green habit shall take his station by their side upon the book shelf!

The adventurous portion of the book is all to which we have attended, and so far we have found much fine humor, good advice, and useful information in all matters touching the nature, the management, and especially the purchase of a horse. We would advise all amateurs to look well, and look quickly into the pages of Caveat Emptor. [The Southern Literary Messenger (August, 1836), p. 593]

ポーが書評した本 (6) クーパーの『ワイアンドッテ』 (1843) Books Reviewed by Poe (6): _Wyandotté, or the Hutted Knoll_ by James Fenimore Cooper [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

ポーは文学書だけじゃなくていろんな本の書評を書きました、けど無論、文学作品の批評も書きました。

Edgar Allan Poe, Review of Wyandotte, or the Hutted Knoll (Graham's Magazine, November 1843)

Wyandotté, or the Hutted Knoll. A tale, by the author of "The Pathfinder," "Deerslayer," "Last of the Mohicans," "Pioneers," "Prairie," &c., &c. Philadelphia, Lea & Blanchard.

〔ジェームズ・フェニモア・クーパー著〕 『ワイアンドッテ、またの名、小屋のある丘』 (『先導者』『鹿殺し』『モヒカン族の最後の者』『開拓者たち』『大草原』等々の作者による物語) フィラデルフィア:ケアリー・リー・アンド・ブランシャード刊〔, 1843. 全2巻, 237pp.+201pp.〕

Cooper Statue in Cooperstown, New York. image via Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Fenimore_Cooper>

クーパー James Fenimore Cooper, 1789-1851 は、チャールズ・ブロックデン・ブラウンやワシントン・アーヴィングに続いて出てきた最初のアメリカの本格的な職業作家で、最初の大作家でした。今日「レザーストッキング・テールズ(皮脚絆物語)Leatherstocking Tales」5部作が最も有名ですけれど、1843年というと、『開拓者たち The Pioneers』(1823)、『モヒカン族の最後の者』(1826)、『大草原 The Prairie』(1827)を三部作的に出してのち十数年を経て、主人公ナッティー・バンポーを生き返らせた(若いころを描いた)『先導者 The Pathfinder』(1840)と『鹿殺し The Deerslayer』(1841)を続けて出して五部作として完結させてまもないころです。扉のページの作者の紹介に挙げられているのがこれら5作品であり、すでにこのころにクーパーが築いていた地位や作家像を想像させるものがあります。

けど、ポーは平気でクーパーに対して批判的なことをあちこちで書いたのでした。

それがなんでなのか、というのはおもしろい問題だし、この書評がなかば語っていることかもしれないけれど、とりあえずおいといて、この書評自体が興味深いのは、つぎの3点くらいかと現在の自分には思われます。

第一に、のちにマーク・トウェインのエッセイ「フェニモア・クーパーの文学的罪状 Fenimore Cooper's Literary Offenses」が問題にするクーパーのスタイル・文体について実践的に批判しているところ(文章の添削を行なってみせる)。

第二に、インディアンと黒人の人物造形について語っていること。(「黒人は例外なくみごとに描かれている。しかしながら、インディアンのワイアンドッテはこの本の偉大な主人公で、『開拓者たち』の作者がこれまで創造したインディアンと比べてあらゆる点において遜色がない。いや実際、この「森の紳士」は、小説家が不滅とした他の同類の主人公たちより優れていると我々は考える」 The negroes are, without exception, admirably drawn. The Indian, Wyandotté, however, is the great feature of the book, and is, in every respect, equal to the previous Indian creations of the author of "The Pioneer." Indeed, we think this "forest gentleman" superior to the other noted heroes of his kind the heroes which have been immortalized by our novelist.)

第三に、 ロマンス作家クーパーに即して story とplot の区分 (Cf. E. M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel [1927]) を徹底してみせると同時に読者の「興味」「関心」(interest)や細部の描写をそれと関連付けて論じること。((A) [. . .] we give assurance that the story is a good one; for Mr. Cooper has never been known to fail, either in the forest or upon the sea. The interest, as usual, has no reference to plot, of which, indeed, our novelist seems altogether regardless, or incapable, but depends, first, upon the nature of the theme; secondly, upon a Robinson-Crusoe-like detail in its management; and thirdly, upon the frequently repeated portraiture of the half-civilized Indian. (B) It will be at once seen that there is nothing original in this story. On the contrary, it is even excessively common-place. The lover, for example, rescued from captivity by the mistress; the Knoll carried through the treachery of an inmate; and the salvation of the besieged, at the very last moment, by a reinforcement arriving, in consequence of a message borne to a friend by one of the besieged, without the cognizance of the others; these, we say, are incidents which have been the common property of every novelist since the invention of letters. And as for plot, there has been no attempt at any thing of the kind.)

第四に、"popular" ということばを使って、大衆小説ないし通俗小説と芸術性について、自身の営みとおそらく比較・差異化しながら語っているらしいこと。

[. . .] and thus there are two great classes of fictions, ―a popular and widely circulated class, read with pleasure, but without admiration in which the author is lost or forgotten; or remembered, if at all, with something very nearly akin to contempt; and then, a class not so popular, nor so widely diffused, in which, at every paragraph, arises a distinctive and highly pleasurable interest, springing from our perception and appreciation of the skill employed, of the genius evinced in the composition. After perusal of the one class, we think solely of the book after reading the other, chiefly of the author. The former class leads to popularity―the latter to fame. In the former case, the books sometimes live, while the authors usually die; in the latter, even when the works perish, the man survives. Among American writers of the less generally circulated, but more worthy and more artistical fictions, we may mention Mr. Brockden Brown, Mr. John Neal, Mr. Simms, Mr. Hawthorne; at the head of the more popular division we may place Mr. Cooper.

(〔・・・・・・〕本はふたつに大別されることになる。・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・

・・・・・・・・・・・・アメリカの作家であまり読まれていないがもっと読まれてしかるべき芸術的に優れた作品の書き手は、ブロックデン・ブラウン氏、ジョン・ニール氏、シムズ氏、ホーソーン氏であり、もっと通俗的なレヴェルの筆頭に私はクーパー氏を置く。)

popular というコトバは多義的でよくわからんです。考えてみようっと。

E-text @Internet Archive: Library, University of California, Davis <http://www.archive.org/stream/wyandotte00cooprich#page/n7/mode/2up>

Gutenberg E-text (1871 rpt.) <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/10434/10434-h/10434-h.htm>

Rpt. London: Routledge, 1856 <http://www.archive.org/stream/wyandotteorhutt00coopgoog#page/n4/mode/2up>

〔2011.1.5朝付記 上の引用部分の訳ができていませんが、下の原文全体にハイパーリンクをはる作業をしました〕

[Edgar Allan Poe, Review of Wyandotte, or the Hutted Knoll]

Wyandotté, or the Hutted Knoll. A tale, by the author of "The Pathfinder," "Deerslayer," "Last of the Mohicans," "Pioneers," "Prairie," &c., &c. Philadelphia, Lea & Blanchard.

Wyandotte, or The Hutted Knoll" is, in its general features, precisely similar to the novels enumerated in the title. It is a forest subject; and, when we say this, we give assurance that the story is a good one; for Mr. Cooper has never been known to fail, either in the forest or upon the sea. The interest, as usual, has no reference to plot, of which, indeed, our novelist seems altogether regardless, or incapable, but depends, first, upon the nature of the theme; secondly, upon a Robinson-Crusoe-like detail in its management; and thirdly, upon the frequently repeated portraiture of the half-civilized Indian. In saying that the interest depends, first, upon the nature of the theme, we mean to suggest that this theme―life in the Wilderness―is one of intrinsic and universal interest, appealing to the heart of man in all phases; a theme, like that of life upon the ocean, so unfailingly omni-prevalent in its power of arresting and absorbing attention, that while success or popularity is, with such a subject, expected as a matter of course, a failure might be properly regarded as conclusive evidence of imbecility on the part of the author. The two theses in question have been handled usque ad nauseam―and this through the instinctive perception of the universal interest which appertains to them. A writer, distrustful of his powers, can scarcely do better than discuss either one or the other. A man of genius will rarely, and should never, undertake either; first, because both are excessively hackneyed; and, secondly, because the reader never fails, in forming his opinion of a book, to make discount, either wittingly or unwittingly, for that intrinsic interest which is inseparable from the subject and independent of the manner in which it is treated. Very few and very dull indeed are those who do not instantaneously perceive the distinction; and thus there are two great classes of fictions, ―a popular and widely circulated class, read with pleasure, but without admiration in which the author is lost or forgotten; or remembered, if at all, with something very nearly akin to contempt; and then, a class not so popular, nor so widely diffused, in which, at every paragraph, arises a distinctive and highly pleasurable interest, springing from our perception and appreciation of the skill employed, of the genius evinced in the composition. After perusal of the one class, we think solely of the book after reading the other, chiefly of the author. The former class leads to popularity―the latter to fame. In the former case, the books sometimes live, while the authors usually die; in the latter, even when the works perish, the man survives. Among American writers of the less generally circulated, but more worthy and more artistical fictions, we may mention Mr. Brockden Brown, Mr. John Neal, Mr. Simms, Mr. Hawthorne; at the head of the more popular division we may place Mr. Cooper.

"The Hutted Knoll," without pretending to detail facts, gives a narrative of fictitious events, similar, in nearly all respects, to occurrences which actually happened during the opening scenes of the Revolution, and at other epochs of our history. It pictures the dangers, difficulties, and distresses of a large family, living, completely insulated, in the forest. The tale commences with a description of the "region which lies in the angle formed by the junction of the Mohawk with the Hudson, extending as far south as the line of Pennsylvania, and west to the verge of that vast rolling plain which composes Western New York"―a region of which the novelist has already frequently written, and the whole of which, with a trivial exception, was a wilderness before the Revolution. Within this district, and on a creek running into the Unadilla, a certain Captain Willoughby purchases an estate, or "patent," and there retires, with his family and dependents, to pass the close of his life in agricultural pursuits. He has been an officer in the British army, but, after serving many years, has sold his commission, and purchased one for his only son, Robert, who alone does not accompany the party into the forest. This party consists of the captain himself; his wife; his daughter, Beulah; an adopted daughter, Maud Meredith; an invalid sergeant, Joyce, who had served under the captain; a Presbyterian preacher, Mr. Woods; a Scotch mason, Jamie Allen; an Irish laborer, Michael O'Hearn; a Connecticut man, Joel Strides; four negroes, Old Plin and Young Plin, Big Smash and Little Smash; eight axe-men; a house-carpenter; a mill-wright, &c., &c. Besides these, a Tuscarora Indian called Nick, or Wyandotté, accompanies the expedition. This Indian, who figures largely in the story, and gives it its title, may be considered as the principal character―the one chiefly elaborated. He is an outcast from his tribe, has been known to Captain Willoughby for thirty years, and is a compound of all the good and bad qualities which make up the character of the half-civilized Indian. He does not remain with the settlers; but appears and re-appears at intervals upon the scene.

Nearly the whole of the first volume is occupied with a detailed account of the estate purchased, (which is termed "The Hutted Knoll" from a natural mound upon which the principal house is built) and of the progressive arrangements and improvements. Toward the close of the volume the Revolution commences; and the party at the "Knoll" are besieged by a band of savages and "rebels," with whom an understanding exists, on the part of Joel Strides, the Yankee. This traitor, instigated by the hope of possessing Captain Willoughby's estate, should it be confiscated, brings about a series of defections from the party of the settlers, and finally, deserting himself, reduces the whole number to six or seven, capable of bearing arms. Captain Willoughby resolves, however, to defend his post. His son, at this juncture, pays him a clandestine visit, and, endeavoring to reconnoitre the position of the Indians, is made captive. The captain, in an attempt at rescue, is murdered by Wyandotté, whose vindictive passions had been aroused by ill-timed allusions, on the part of Willoughby, to floggings previously inflicted, by his orders, upon the Indian. Wyandotté, however, having satisfied his personal vengeance, is still the ally of the settlers. He guides Maud, who is beloved by Robert, to the hut in which the latter is confined, and effects his escape. Aroused by this escape, the Indians precipitate their attack upon the Knoll, which, through the previous treachery of Strides in ill-hanging a gate, is immediately carried. Mrs. Willoughby, Beulah, and others of the party, are killed. Maud is secreted and thus saved by Wyandotté. At the last moment, when all is apparently lost, a reinforcement appears, under command of Evert Beekman, the husband of Beulah; and the completion of the massacre is prevented. Woods, the preacher, had left the Knoll, and made his way through the enemy, to inform Beekman of the dilemma of his friends. Maud and Robert Willoughby are, of course, happily married. The concluding scene of the novel shows us Wyandotté repenting the murder of Willoughby, and converted to Christianity through the agency of Woods.

It will be at once seen that there is nothing original in this story. On the contrary, it is even excessively common-place. The lover, for example, rescued from captivity by the mistress; the Knoll carried through the treachery of an inmate; and the salvation of the besieged, at the very last moment, by a reinforcement arriving, in consequence of a message borne to a friend by one of the besieged, without the cognizance of the others; these, we say, are incidents which have been the common property of every novelist since the invention of letters. And as for plot, there has been no attempt at any thing of the kind. The tale is a mere succession of events, scarcely any one of which has any necessary dependence upon any one other. Plot, however, is, at best, an artificial effect, requiring, like music, not only a natural bias, but long cultivation of taste for its full appreciation; some of the finest narratives in the world―"Gil-Blas" and "Robinson Crusoe," for example―have been written without its employment; and "The Hutted Knoll," like all the sea and forest novels of Cooper, has been made deeply interesting, although depending upon this peculiar source of interest not at all. Thus the absence of plot can never be critically regarded as a defect; although its judicious use, in all cases aiding and in no case injuring other effects, must be regarded as of a very high order of merit.

There are one or two points, however, in the mere conduct of the story now before us, which may, perhaps, be considered as defective. For instance, there is too much obviousness in all that appertains to the hanging of the large gate. In more than a dozen instances, Mrs. Willoughby is made to allude to the delay in the hanging; so that the reader is too positively and pointedly forced to perceive that this delay is to result in the capture of the Knoll. As we are never in doubt of the fact, we feel diminished interest when it actually happens. A single vague allusion, well-managed, would have been in the true artistical spirit.

Again; we see too plainly, from the first, that Beekman is to marry Beulah, and that Robert Willoughby is to marry Maud. The killing of Beulah, of Mrs. Willoughby, and Jamie Allen, produces, too, a painful impression which does not properly appertain to the right fiction. Their deaths affect us as revolting and supererogatory; since the purposes of the story are not thereby furthered in any regard. To Willoughby's murder, however distressing, the reader makes no similar objection; merely because in his decease is fulfilled a species of poetical justice. We may observe here, nevertheless, that his repeated references to his flogging the Indian seem unnatural, because we have otherwise no reason to think him a fool, or a madman, and these references, under the circumstances, are absolutely insensate. We object, also, to the manner in which the general interest is dragged out, or suspended. The besieging party are kept before the Knoll so long, while so little is done, and so many opportunities of action are lost, that the reader takes it for granted that nothing of consequence will occur―that the besieged will be finally delivered. He gets so accustomed to the presence of danger that its excitement, at length, departs. The action is not sufficiently rapid. There is too much procrastination. There is too much mere talk for talk's sake. The interminable discussions between Woods and Captain Willoughby are, perhaps, the worst feature of the book, for they have not even the merit of referring to the matters on hand. In general, there is quite too much colloquy for the purpose of manifesting character, and too little for the explanation of motive. The characters of the drama would have been better made out by action; while the motives to action, the reasons for the different courses of conduct adopted by the dramatis personÆ, might have been made to proceed more satisfactorily from their own mouths, in casual conversations, than from that of the author in person. To conclude our remarks upon the head of ill-conduct in the story, we may mention occasional incidents of the merest melodramatic absurdity: as, for example, at page 156, of the second volume, where "Willoughby had an arm round the waist of Maud, and bore her forward with a rapidity to which her own strength was entirely unequal." We may be permitted to doubt whether a young lady of sound health and limbs, exists, within the limits of Christendom, who could not run faster, on her own proper feet, for any considerable distance, than she could be carried upon one arm of either the Cretan Milo or of the Hercules Farnese.

On the other hand, it would be easy to designate many particulars which are admirably handled. The love of Maud Meredith for Robert Willoughby is painted with exquisite skill and truth. The incident of the tress of hair and box is naturally and effectively conceived. A fine collateral interest is thrown over the whole narrative by the connection of the theme with that of the Revolution; and, especially, there is an excellent dramatic point, at page 124 of the second volume, where Wyandotté, remembering the stripes inflicted upon him by Captain Willoughby, is about to betray him to his foes, when his purpose is arrested by a casual glimpse, through the forest, of the hut which contains Mrs. Willoughby, who had preserved the life of the Indian, by inoculation for the small-pox.

In the depicting of character, Mr. Cooper has been unusually successful in "Wyandotté." One or two of his personages, to be sure, must be regarded as little worth. Robert Willoughby, like most novel heroes, is a nobody; that is to say, there is nothing about him which may be looked upon as distinctive. Perhaps he is rather silly than otherwise; as, for instance, when he confuses all his father's arrangements for his concealment, and bursts into the room before Strides afterward insisting upon accompanying that person to the Indian encampment, without any possible or impossible object. Woods, the parson, is a sad bore, upon the Dominie Sampson plan, and is, moreover, caricatured. Of Captain Willoughby we have already spoken―he is too often on stilts. Evert Beekman and Beulah are merely episodical. Joyce is nothing in the world but Corporal Trim―or, rather, Corporal Trim and water. Jamie Allen, with his prate about Catholicism, is insufferable. But Mrs. Willoughby, the humble, shrinking, womanly wife, whose whole existence centres in her affections, is worthy of Mr. Cooper. Maud Meredith is still better. In fact, we know no female portraiture, even in Scott, which surpasses her; and yet the world has been given to understand, by the enemies of the novelist, that he is incapable of depicting a woman. Joel Strides will be recognized by all who are conversant with his general prototypes of Connecticut. Michael O'Hearn, the County Leitrim man, is an Irishman all over, and his portraiture abounds in humor; as, for example, at page 31, of the first volume, where he has a difficulty with a skiff, not being able to account for its revolving upon its own axis, instead of moving forward! or, at page 132, where, during divine service, to exclude at least a portion of the heretical doctrine, he stops one of his ears with his thumb; or, at page 195, where a passage occurs so much to our purpose that we will be pardoned for quoting it in full. Captain Willoughby is drawing his son up through a window, from his enemies below. The assistants, placed at a distance from this window to avoid observation from without, are ignorant of what burthen is at the end of the rope:

"The men did as ordered, raising their load from the ground a foot or two at a time. In this manner the burthen approached, yard after yard, until it was evidently drawing near the window.

" 'It's the captain hoisting up the big baste of a hog, for provisioning the hoose again a saige,' whispered Mike to the negroes, who grinned as they tugged; 'and, when the craitur squails, see to it, that ye do not squail yourselves.'

"At that moment, the head and shoulders of a man appeared at the window. Mike let go the rope, seized a chair, and was about to knock the intruder upon the head; but the captain arrested the blow.

" 'It's one o' the vagabone Injins that has undermined the hog and come up in its stead,' roared Mike.

" 'It's my son,' said the captain; 'see that you are silent and secret.' "

The negroes are, without exception, admirably drawn. The Indian, Wyandotté, however, is the great feature of the book, and is, in every respect, equal to the previous Indian creations of the author of "The Pioneer." Indeed, we think this "forest gentleman" superior to the other noted heroes of his kind the heroes which have been immortalized by our novelist. His keen sense of the distinction, in his own character, between the chief, Wyandotté, and the drunken vagabond, Sassy Nick; his chivalrous delicacy toward Maud, in never disclosing to her that knowledge of her real feelings toward Robert Willoughby, which his own Indian intuition had discovered; his enduring animosity toward Captain Willoughby, softened, and for thirty years delayed, through his gratitude to the wife; and then, the vengeance consummated, his pity for that wife conflicting with his exultation at the deed―these, we say, are all traits of a lofty excellence indeed. Perhaps the most effective passage in the book, and that which, most distinctively, brings out the character of the Tuscarora, is to be found at pages 50, 51, 52 and 53 of the second volume, where, for some trivial misdemeanor, the captain threatens to make use of the whip. The manner in which the Indian harps upon the threat, returning to it again and again, in every variety of phrase, forms one of the finest pieces of mere character-painting with which we have any acquaintance.

The most obvious and most unaccountable faults of "The Hutted Knoll," are those which appertain to the style―to the mere grammatical construction; ―for, in other and more important particulars of style, Mr. Cooper, of late days, has made a very manifest improvement. His sentences, however, are arranged with an awkwardness so remarkable as to be matter of absolute astonishment, when we consider the education of the author, and his long and continual practice with the pen. In minute descriptions of localities, any verbal inaccuracy, or confusion, becomes a source of vexation and misunderstanding, detracting very much from the pleasure of perusal; and in these inaccuracies "Wyandotté" abounds. Although, for instance, we carefully read and re-read that portion of the narrative which details the situation of the Knoll, and the construction of the buildings and walls about it, we were forced to proceed with the story without any exact or definite impressions upon the subject. Similar difficulties, from similar causes, occur passim throughout the book. For example: at page 41, vol. I:

"The Indian gazed at the house, with that fierce intentness which sometimes glared, in a manner that had got to be, in its ordinary aspects, dull and besotted." This it is utterly impossible to comprehend. We presume, however, the intention is to say that although the Indian's ordinary manner (of gazing) had "got to be" dull and besotted, he occasionally gazed with an intentness that glared, and that he did so in the instance in question. The "got to be" is atrocious―the whole sentence no less so.

Here, at page 9, vol. I., is something excessively vague: "Of the latter character is the face of most of that region which lies in the angle formed by the junction of the Mohawk with the Hudson," &c. &c. The Mohawk, joining the Hudson, forms two angles, of course, ―an acute and an obtuse one; and, without farther explanation, it is difficult to say which is intended.

At page 55, vol. I., we read: ―"The captain, owing to his English education, had avoided straight lines, and formal paths; giving to the little spot the improvement on nature which is a consequence of embellishing her works without destroying them. On each side of this lawn was an orchard, thrifty and young, and which were already beginning to show signs of putting forth their blossoms." Here we are tautologically informed that improvement is a consequence of embellishment, and supererogatorily told that the rule holds good only where the embellishment is not accompanied by destruction. Upon the "each orchard were" it is needless to comment.

At page 30, vol. I., is something similar, where Strides is represented as "never doing any thing that required a particle more than the exertion and strength that were absolutely necessary to effect his object." Did Mr. C. ever hear of any labor that required more exertion than was necessary? He means to say that Strides exerted himself no farther than was necessary―that's all.

At page 59, vol. I., we find this sentence―"He was advancing by the only road that was ever traveled by the stranger as he approached the Hut; or, he came up the valley." This is merely a vagueness of speech. "Or" is intended to imply "that is to say." The whole would be clearer thus―"He was advancing by the valley―the only road traveled by a stranger approaching the Hut." We have here sixteen words, instead of Mr. Cooper's twenty-five.

At page 8, vol. II., is an unpardonable awkwardness, although an awkwardness strictly grammatical. "I was a favorite, I believe, with, certainly was much petted by, both." Upon this we need make no farther observation. It speaks for itself.

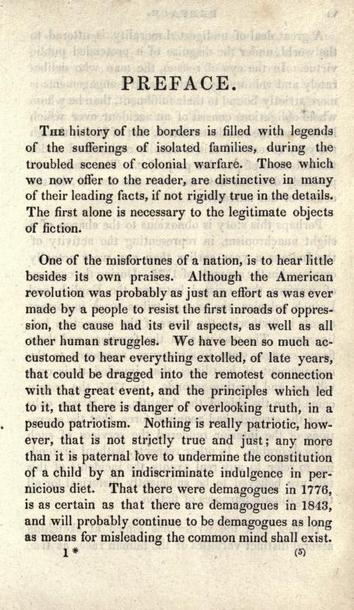

We are aware, however, that there is a certain air of unfairness, in thus quoting detached passages, for animadversion of this kind; for, however strictly at random our quotations may really be, we have, of course, no means of proving the fact to our readers; and there are no authors, from whose works individual inaccurate sentences may not be culled. But we mean to say that Mr. Cooper, no doubt through haste or neglect, is remarkably and especially inaccurate, as a general rule; and, by way of demonstrating this assertion, we will dismiss our extracts at random, and discuss some entire page of his composition. More than this: we will endeavor to select that particular page upon which it might naturally be supposed he would bestow the most careful attention. The reader will say at once―"Let this be his first page―the first page of his Preface." This page, then, shall be taken of course.

"The history of the borders is filled with legends of the sufferings of isolated families, during the troubled scenes of colonial warfare. Those which we now offer to the reader, are distinctive in many of their leading facts, if not rigidly true in the details. The first alone is necessary to the legitimate objects of fiction."

"Abounds with legends," would be better than "is filled with legends;" for it is clear that if the history were filled with legends, it would be all legend and no history. The word "of," too, occurs, in the first sentence, with an unpleasant frequency. The "those" commencing the second sentence, grammatically refers to the noun "scenes," immediately preceding, but is intended for "legends." The adjective "distinctive" is vaguely and altogether improperly employed. Mr. C. we believe means to say, merely, that although the details of his legends may not be strictly true, facts similar to his leading ones have actually occurred. By use of the word "distinctive," however, he has contrived to convey a meaning nearly converse. In saying that his legend is " distinctive" in many of the leading facts, he has said what he, clearly, did not wish to say―viz.: that his legend contained facts which distinguished it from all other legends―in other words, facts never before discussed in other legends, and belonging peculiarly to his own. That Mr. C. did mean what we suppose, is rendered evident by the third sentence―"The first alone is necessary to the legitimate objects of fiction." This third sentence itself, however, is very badly constructed. "The first" can refer, grammatically, only to "facts;" but no such reference is intended. If we ask the question―what is meant by "the first?"―what "alone is necessary to the legitimate objects of fiction?" ―the natural reply is, "that facts similar to the leading ones have actually happened." This circumstance is alone to be cared for―this consideration "alone is necessary to the legitimate objects of fiction."

"One of the misfortunes of a nation is to hear nothing besides its own praises." This is the fourth sentence, and is by no means lucid. The design is to say that individuals composing a nation, and living altogether within the national bounds, hear from each other only praises of the nation, and that this is a misfortune to the individuals, since it mis-leads them in regard to the actual condition of the nation. Here it will be seen that, to convey the intended idea, we have been forced to make distinction between the nation and its individual members; for it is evident that a nation is considered as such only in reference to other nations; and thus, as a nation, it hears very much "besides its own praises;" that is to say, it hears the detractions of other rival nations. In endeavoring to compel his meaning within the compass of a brief sentence, Mr. Cooper has completely sacrificed its intelligibility.

The fifth sentence runs thus: ―"Although the American Revolution was probably as just an effort as was ever made by a people to resist the first inroads of oppression, the cause had its evil aspects, as well as all other human struggles."

The American Revolution is here improperly called an "effort." The effort was the cause, of which the Revolution was the result. A rebellion is an "effort" to effect a revolution. An "inroad of oppression" involves an untrue metaphor; for "inroad" appertains to aggression, to attack, to active assault. "The cause had its evil aspects, as well as all other human struggles," implies that the cause had not only its evil aspects, but had, also, all other human struggles. If the words must be retained at all, they should be thus arranged―"The cause like [or as well as] all other human struggles, had its evil aspects;" or better thus―"The cause had its evil aspect, as have all human struggles." "Other" is superfluous.

The sixth sentence is thus written: ―"We have been so much accustomed to hear every thing extolled, of late years, that could be dragged into the remotest connection with that great event, and the principles which led to it, that there is danger of overlooking truth in a pseudo patriotism." The "of late years," here, should follow the "accustomed," or precede the "We have been;" and the Greek "pseudo" is objectionable, since its exact equivalent is to be found in the English "false." "Spurious" would be better, perhaps, than either.

Inadvertences such as these sadly disfigure the style of "The Hutted Knoll;" and every true friend of its author must regret his inattention to the minor morals of the Muse. But these "minor morals," it may be said, are trifles at best. Perhaps so. At all events, we should never have thought of dwelling so pertinaciously upon the unessential demerits of "Wyandotté," could we have discovered any more momentous upon which to comment. [Graham's Magazine (November 1843)]

ポーが書評した本 (7) シガニー夫人の『ツィンツェンドルフ、その他の詩』 (1836) Books Reviewed by Poe (7): _Zinzendorff, and Other Poems_ by Mrs. L. H. Sigourney [ポーの書評 Poe's Book Reviews]

Zinzendorff, and Other Poems. By Mrs. L. H. Sigourney. New York: Leavitt, Lord and Co. 1836. 300pp.

L・H・シガニー夫人著 『ツィンツェンドルフ、その他の詩』

E-text at Open Library [New York Public Library; MSN] <http://openlibrary.org/works/OL7787359W/Zinzendorff> Internet Archive zinzendorffando00sigogoog

ポー の書評は、『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー The Southern Literary Messenger』1836年1月号所収。41ページから68ページにかけての十のReview からなる "Critical Notices" の最初のもので、実は、1835年に出版された他の女性詩人(Miss [Hannah Flagg] Gould, 1789-1865 と Mirs. [Elizabeth Fries] Ellet, 1818-77) の詩集も合わせて俎上にのせている。

ツィンツェンドルフというとモラヴィア派で有名だけれど、モラヴィア兄弟団 (Moravian Brethren) ・モラヴィア教会 (Moravian Church) は15世紀にボヘミアで設立されていたのが17世紀に再興されたもので、それをツィンツェンドルフがさらに再興させたということらしい。Zinzendorf を辞書をあらためて引いてみると、研究社の大英和は「ツィンツェンドルフ《1700-60》ドイツの宗教改革者でMoravian兄弟団の設立者」と書かれ、ジーニアス英和大辞典は「・・・ドイツの宗教指導者; Moravian教会を設立」と記し、リーダーズ英和辞典は「ボヘミア兄弟団(Bohemian Brethren) 直系のモラヴィア兄弟団の設立者」としている。ランダムハウス英和大辞典はモラヴィアへの言及はなくて、「ヘルンフート派(Herrnhuter) を創設 (1722)」と記述している。百科事典をみると、ツィンツェンドルフはドレスデンで迫害を逃れたボヘミア兄弟団員と知り合い、これがヘルンフート兄弟団の始まりとなったということだ。

アメリカ文学で有名(じゃないかもしれないけど意外なので気になる)なのは、クーパーの造形したナッティー・バンポーがモラヴィア教徒であることかしら。C・B・ブラウンにも出てきたような気がする。

リディア・ハントリー・シガニー L[ydia] H[untley] Sigourney, 1791-1865 はコネティカット州ハートフォードの女性詩人で、ポーもふれているように『サザン・リテラリー・メッセンジャー』誌にも寄稿したひと。

ポーはシガニー夫人の詩が、(1) 統一Unity を欠いていることと、(2) イギリスの女性詩人Felicia Hemans の模倣が強いことを批判するけれど、versification (なんと訳したらいいのでしょう)を基本的には褒め、具体的にさまざまな詩行を引いて丁寧に解説しています。

Zinzendorff, and Other Poems. By Mrs. L. H. Sigourney.

New York: Leavitt, Lord and Co. 1836.

//////////////////////////////////////////////////////////

CRITICAL NOTICES.

MRS. SIGOURNEY―MISS GOULD―MRS. ELLET.

Zinzendorff, and other Poems. By Mrs. L. H. Sigourney, New

York:

Published by Leavitt, Lord & Co. 1836.

Poems—By Miss H. F. Gould, Third Edition. Boston: Hilliard,

Gray & Co. 1835.

Poems; Translated and Original. By Mrs. E. F. Ellet.

Philadelphia:

Key and Biddle. 1835.

Mrs. Sigourney has been long known as an author. Her earliest publication was reviewed about twenty years ago, in the North American. She was then Miss Huntley. The fame which she has since acquired is extensive; and we, who so much admire her virtues and her talents, and who have so frequently expressed our admiration of both in this Journal—we, of all persons—are the least inclined to call in question the justice or the accuracy of the public opinion, by which has been adjudged to her so high a station among the literati of our land. Some things, however, we cannot pass over in silence. There are two kinds of popular reputation, —or rather there are two roads by which such reputation may be attained: and it appears to us an idiosyncrasy which distinguishes mere fame from most, or perhaps from all other human ends, that, in regarding the intrinsic value of the object, we must not fail to introduce, as a portion of our estimate, the means by which the object is acquired. To speak less abstractedly. Let us suppose two writers having a reputation apparently equal—that is to say, their names being equally in the mouths of the people—for we take this to be the most practicable test of what we choose to term apparent popular reputation. Their names then are equally in the mouths of the people. The one has written a great work—let it be either an Epic of high rank, or something which, although of seeming littleness in itself, is yet, like the Christabelle of Coleridge, entitled to be called great from its power of creating intense emotion in the minds of great men. And let us imagine that, by this single effort, the author has attained a certain quantum of reputation. We know it to be possible that another writer of very moderate powers may build up for himself, little by little, a reputation equally great—and this, too, merely by keeping continually in the eye, or by appealing continually with little things, to the ear, of that great, overgrown, and majestical gander, the critical and bibliographical rabble.

It would be an easy, although perhaps a somewhat disagreeable task, to point out several of the most popular writers in America—popular in the above mentioned sense—who have manufactured for themselves a celebrity by the very questionable means, and in the very questionable manner, to which we have alluded. But it must not be thought that we wish to include Mrs. Sigourney in the number. By no means. She has trod, however, upon the confines of their circle. She does not owe her reputation to the chicanery we mention, but it cannot be denied that it has been thereby greatly assisted. In a word—no single piece which she has written, and not even her collected works as we behold them in the present volume, and in the one published some years ago, would fairly entitle her to that exalted rank which she actually enjoys as the authoress, time after time, of her numerous, and, in most instances, very creditable compositions. The validity of our objections to this adventitious notoriety we must be allowed to consider unshaken, until it can be proved that any multiplication of zeros will eventuate in the production of a unit.

We have watched, too, with a species of anxiety and vexation brought about altogether by the sincere interest we take in Mrs. Sigourney, the progressive steps by which she has at length acquired the title of the "American Hemans." Mrs. S. cannot conceal from her own discernment that she has acquired this title solely by imitation. The very phrase "American Hemans" speaks loudly in accusation: and we are grieved that what by the over-zealous has been intended as complimentary should fall with so ill-omened a sound into the ears of the judicious. We will briefly point out those particulars in which Mrs. Sigourney stands palpably convicted of that sin which in poetry is not to be forgiven.