醜いわが子――子らよのパート3 My Hideous Progeny: My Chillun, Part 3 [Marginalia 余白に]

前の記事で、ちょっと投げやりに『フランケンシュタイン』の「まえがき」を引きっぱにしたところがあって、気になっていました。メアリー・シェリーが「醜いわが子」と呼んでいるのはフランケンシュタインの怪物ではなくて、作品(本)のことだという自信はあったのですけれど、なんで我が子を hideous と呼ぶか。いかにもモンスターのことを指しているように感じられます。

で、調べてみると、実際、"hideous progeny" というフレーズは怪物を指すごとく受容・使用されている場合が多々あるのでした。

(a)

The creature – "my hideous progeny" – was not given a name by Mary Shelley, and is only referred to as "The Monster", "The Creature" and "Frankenstein's Monster", or as Victor Frankenstein called his creation more commonly, "the fiend." After the release of James Whale's popular 1931 film Frankenstein, the filmgoing public immediately began speaking of the monster itself as Frankenstein. A reference to this occurs in The Bride of Frankenstein (1935) and in several subsequent films in the series, as well as in film titles such as Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. 〔"Frankenstein - The name of the creature" <http://www.experiencefestival.com/a/Frankenstein_-_The_name_of_the_creature/id/5062662> 太字で強調付加〕

(b)

この場面は、様々な点で、メアリーの「現代のプロメテウス」ヴィクターが創り出した”hideous progeny”を反転させて、ハイブリッドは怪物かそれとも新しい美しい創造なのかという問いに、新しい答えを提示しようとしている。〔アルヴィ宮本なほ子「ロマン派的身体――Percy & Mary Shelley を中心に」 <http://web.hc.keio.ac.jp/~asuzuki/BMC-HP/pastaction/past2000/paper/miyamoto.html> 太字で強調付加〕

(c)

Mary Poovey, The Proper Lady and the Woman Writer: Ideology as Style in the Work of Mary Wollstonecraft, Mary Shelley, and Jane Austen. Chicago: U of Chicago P. 1984. Ch. 4: "'My Hideous Progeny': The Lady and the Monster."

もっとも次のように欲張って、"hideous progeny" の指示を作品・怪物・著者の三つであるというような論文(?) もあります。――

Reinforcing this emphasis on hypertext as "femininely" embodied are links that re-embody passages from Shelley's text into contexts which subtly or extravagantly alter their meaning. A stunning example is the famous passage from the 1831 preface where Mary Shelley bids her "hideous progeny go forth and prosper" (qtd. in story/severance/hideous progeny). "I have an affection for it, for it was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words which found no true echo in my heart. Its several pages speak of many a walk, many a drive, and many a conversation, when I was not alone; and my companion was one who, in this world, I shall never see more. But this is for myself; my readers have nothing to do with these associations" (qtd. in story/severance/hideous progeny). In the context of Frankenstein, "hideous progeny" can be understood as referring both to the text and to the male monster. As Anne Mellor points out, taking the text as the referent places Mary Shelley in the tradition of female writers of Gothic novels who were exposing the dark underside of British society. When the monster is taken as the referent, the passage suggests that Mary Shelley's textual creature expresses the fear attending birth in an age of high mortality rates for women and infants--a fear that Shelley was to know intimately from wrenching personal experience. Moreover, in Barbara Johnson's reading of Frankenstein, Shelley is also giving birth to herself as a writer in this text, so her authorship also becomes a "hideous progeny." The rich ambiguities that inhere in the phrase make Jackson's transformation of it all the more striking. 〔Katharine Hayles, "Flickering Connectivities in Shelley Jackson's Patchwork Girl: The Importance of Media-Specific Analysis" (2000); Annabel Margaret van Baren, "Stitch and Split: Feminist Alternatives to Frankensteinian Myths in Shelley Jackson's Patchwork Girl" (2007)〕

まあ、そういうレトリックを誘うものがあるのだろう。それでも、確認しておかねばならぬのは、作品中被造物(怪物)と創造者(科学者)がダブリングを起こしているとはいえ、そしてその後の、特に映画のイメジによってフランケンシュタインが怪物の名と混同される事態が起こったとはいえ、フランケンシュタイン Frankenstein は「Frankenstein's monster フランケンシュタインの怪物」をつくった科学者の名前であり、作品(本)の「フランケンシュタイン」が作者のprogenyであると言うことが即座に怪物につながらないということです。つまり、メアリー・シェリーの hideous progeny が第一に作品『フランケンシュタイン』で、第二にフランケンシュタインだとして、その第二のものは怪物をhideous progeny として創り出す人間を指しているということ。

そして、ここではなによりもまずは小説(作品)を指しているのであって、それはそのあとの "it" の指示と内容を考えれば明らかだと思います。

And now, once again, I bid my hideous progeny go forth and prosper. I have an affection for it, for it was the offspring of happy days, when death and grief were but words, which found no true echo in my heart. Its several pages speak of many a walk, many a drive, and many a conversation, when I was not alone; and my companion was one who, in this world, I shall never see more. But this is for myself; my readers have nothing to do with these associations.

それにしても、自作を子供(オルコットとはちがって progeny ということばですけれど)と呼びながらそれに hideous という形容をつけるのはひでーなーとは思います。

メアリー・シェリー (Mary Shelley, 1797-1951) の母親は有名な女権論者のメアリー・ウルストンクラフト (Mary Wollstonecraft, 1759-97) で、父親は作家でアナキストのウィリアム・ゴドウィン (William Godwin, 1756-1836) ですが、母親はメアリーを生んで10日くらいして産褥熱で亡くなっています。メアリーは妻帯者であった詩人のシェリーと不倫をして、奥さんはハイドパーク内のSerpentine 池に身を投げて自殺(1816年12月)。メアリーは1816年暮の結婚前も含めて少なくとも4度は妊娠しますが、1815年に早産で生まれた女の子は2週間で死去、1816年1月に生まれた第二子William は1819年6月に亡くなります。1817年9月には第三子のClara を産んでいますが1818年9月に亡くなります。1819年11月第四子Percy Florence 誕生。こういう、自らの出産と母親の出産に関する辛い実体験が、子供として本を生むという比喩において暗い影を落としたということはあるのでしょうか。ゴシック小説を女性が書くという伝統は今日の大衆小説の一分野としての gothics まであるとはいえ、その恐怖は(フィジカルな)ホラーというよりはテラーが一般的だったのを、ホラーのモンスターを創造したことへのなんらかの実人生の投影的な自覚があったのでしょうか。

オルコット (1832-88) の両親もフェミニズムを含む進歩的な思想に傾倒していましたが、母親のAbigail は1877年まで生きて『若草物語』の Mrs. March のモデルとなっています。オルコットは生涯独身を通して、父親の超絶主義哲学者ブロンソン・オルコット (Amos Bronson Alcott, 1799-1888) が亡くなった1888年3月4日の二日後に55歳の生涯を閉じています。オルコットのほうは、現実の体験がないぶん比喩が抽象化ないし夢想化されているのでしょうか。

//////////////////////////////////////

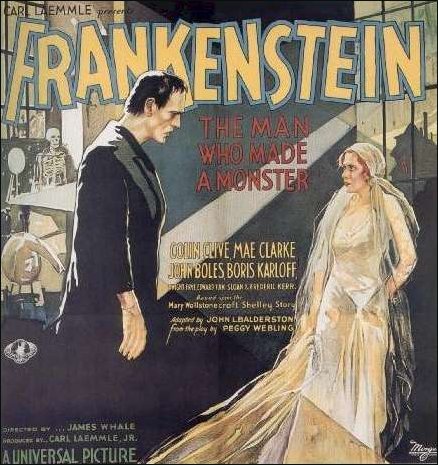

Frankenstein: The Man Who Made a Monster (1931), image via "Frankenstein Links" Bibi's box <http://bibi.org/2005/09/frankenstein_li/> 〔Bibi さんのブログ 2005.9.20〕

.jpg)

Frankenstein: The Man Who Made a Monster (1931), image via "Frankenstein (1931 film)" Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frankenstein_(1931_film)>

-d8b0c.jpg)

コメント 0