ストレンジャー・イン・パラダイス、またはアゲイン Stranger in Paradise; or Again [Marginalia 余白に]

暮れにクリスマスの気分に浮かれて、"Stranger in Paradise" について書き始めて、なんとなく正月も書いたりしたのですけれど――「楽園の他所者 Stranger in Paradise [2009/12/25]」「"Stranger in Paradise" の不思議な日本語訳 A Stranger Translation of "Stranger in Paradise" [2009/12/26]」「ミュージカル『キスメット』のなかの "Stranger in Paradise" "Stranger in Paradise" in the Musical Kismet (1953) [2009/12/26]」「ストレンジャー・イン・パラダイスふたたび Stranger in Paradise Again [2010/01/09]」――暮れからテレビから聞こえてくるCMをたぶん平均1,2日おきくらいにほぼぼけ~っと聞きつづけ、声の感じは1953年初演のミュージカル『キスメット Kismet』 の、ブロードウェイのストライキ中にプロモーションとして抜擢されたトニー・ベネット (Tony Bennett, 1926 - ) なのだけれど、歌詞がなんだかちがうにゃ~、とひと月近くたって思いましたw。

Time again~♪

って、聞こえる歌詞。

で、調べてみると、これ(JR東海のCM曲)は、日本人草間和夫が「作詞」、そして名前からすると日本人 のMISUMI が英訳した歌詞で、日本で活躍している外国人ふたりがレコーディングして2006年に出た「Again」という曲なのだとようやく知りました。

つぎURLはJR東海のページで、「JR東海 | うまし うるわし 奈良 | うましうるわし奈良 キャンペーンソング」(音源つき)――<http://nara.jr-central.co.jp/campaign/song/index.html>

しかし、Donna Burke というのは女声で女性です。Nello Algelucci というひとはイタリア人のギタリストのようなのですが、彼の声が別ヴァージョンとしてあるのでしょうか。

YouTube の過去CM再生リストみたいなもの――<http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1cRC7BzYub8&feature=PlayList&p=82C6ECB7AD00D2DC&index=36>

2009年師走13日の「サンデーソングブック」の山下達郎のおはなしとして、9thNUTSのブログ「未来の自分が振り返る」<http://yamashitatatsuro.blog78.fc2.com/blog-entry-68.html>に書きとめられていること――

以前、JR東海のCMで流れていた”ストレンジャー・イン・パラダイス”絶対にフランクシナトラの歌でお願いします。どこを探してもシナトラでこの曲が無いと言われました。何故テレビで流れていたのでしょう?

教えてください。

達郎氏:

「これ、フランク・シナトラと勘違いされたんだと思います。これ、奈良のなんかのCMですが、あれは、トニー・ベネットだったと記憶しています。いろんな人のバージョン聴きましたが、フランク・シナトラが”ストレンジャー・イン・パラダイス”を歌っているというのは、今まで聞いたことがありません。不勉強なので知らないのかもしれませんが、トニー・ベネットと勘違いされているのではないかと思います。

それでも納得いかなければJR東海に問い合わせてみますが、今日は、これが一番押しが強いお便りだったのでご紹介しました。」

誰の声やねん。合成映像ならぬ合成音声なのかしら。

ま、それはそれとして、この「Again」の正式なタイトルは、 "Again: Ancient Place, the Destination Is Surely True . . ." (表記ちがうかも) というらしいのですが、1番の冒頭は、Time again, take my heart to a gentle place. ききとれず(汗) Am I [??]dreaming again and again, in a silence [??] where you remain. So time will as a nation as old and new, ききとれず(汗) destination as surely true as used to be ききとれず(汗) というのです。 なんかとても日本人くさいです。耳医者いってこようかな。

//////////////////

Tony Bennett, Official Website <http://www.tonybennett.net/>

Tony Bennett Art | Official Website <http://www.benedettoarts.com/index2.html> 〔Anthony Benedetto という画家として〕

大天使ミカエルのこと The Archangel Michael [Marginalia 余白に]

『あしながおじさん』1年生10月10日の手紙の冒頭。――

Did you ever hear of Michael Angelo?

He was a famous artist who lived in Italy in the Middle Ages. Everybody in English Literature seemed to know about him, and the whole class laughed because I thought he was an archangel. He sounds like an archangel, doesn't he? (Penguin Classics 16)

(ミケル・アンジェロってお聞きになったことありますか?

中世にイタリアに住んでいた有名な芸術家です。英文学のクラスに出ているひとは、みんなこのひとのことを知っているらしくて、わたしが大天使だと思ったというのでクラス全部が笑いました。彼って大天使みたいに聞こえるでしょ?

英語の Michael Angelo あるいは Michelangelo の発音は、「舞妓安寿郎」、いや「マイコゥアンジェロウ」みたいなものでしょうが、日本語ウィキペディアの「ミケランジェロ」の記述を信じれば、そもそも、「名前はミカエル(Michael)と天使(angelo)を併せたもの」でした。そのときのMichael が大天使の名前としてなのか、人名としてなのか、結局同じことなのか、はわかりませんが、ジュディーが「大天使みたい」といっているのは、大天使ミカエル+エンジェルとというふうに、ダブルで耳に響いてきたからにほかなりません。(書きそびれましたが、これは2月10日の記事「マイケル・アンジェローとミケランジェロ Michael Angelo or Michelangelo [Daddy-Long-Legs]」のつづきです。)

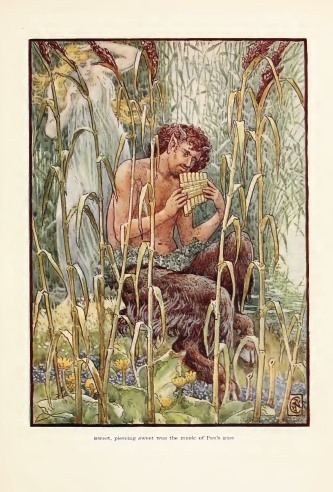

大天使 archangels については、数がいくつだ(「三大天使」「四大天使」「七大天使」)とか宗派・宗教による違いとか、ウィキペディアが薀蓄を傾けているし、ほかのサイトでも薀蓄が傾けられているので、それを参照していただけばよいのですが、中心となる三大天使についてかいつまんでいうと、洗礼者ヨハネの誕生を告げたりマリアに受胎告知 (Annunciation) するのがガブリエル(そういう点では天使の原義の "messenger" の役まわりですけれど、伝統的に、終末を告げるラッパを鳴らすのもガブリエルだとされています ("Gabriel's horn [trumpet]"))、そして旧約の「ダニエル書」ではイスラエルの守護者としてあらわれ、新約の「黙示録」で天使軍を率いて赤い竜と戦うとされるのがミカエル(だからミカエルは軍人の守護者になっている)、そして旧約聖書外典(カトリックでは正典)の「トビト書 The Book of Tobit [Tobias]」に描かれる、人間の姿をしてトビトの息子のトビアスの旅に犬と一緒に同行し、父トビトの目を治したり、悪魔 asmodeus に憑りつかれた花嫁のサラを救ったりするのがラファエロです(このラファエロはイスラム教ではイズラフェル Israfel にあたるとされますが、イズラフェルというのはあのエドガー・アラン・ポーのあだ名になっている、音楽をつかさどる天使で、やっぱり世の終末に最後の審判の裁きを知らせるラッパを吹く役回りももっています)。あ、かいつままないで薀蓄を傾けてしまいましたw。

ラファエルとトビアス(と犬)を描いた絵を多数添えて物語を語る記述が英語のウィキペディア "The Book of Tobit" にあります。魚釣りの絵とか悪魔退治の絵とかあって楽しいです。

そして、ラファエロがトビト書にしか出てこないからか、ミカエルとガブリエルも友情出演(?)するモチーフも絵画にはあります。――

Fra' Filippo Lippi (1406-69), The Three Archangels and the Young Tobias

左から、ミカエル、犬、ラファエル、トビアス、ガブリエル。

_TheThreeArchangelsandTobias-b67e0.jpg)

Domenico De Michellino (1417-91), Tobias and the Three Archangels

左端の、なべを兜代わりにかぶっているのがミカエルです。つぎはラファエル、つぎはトビアス、手前に犬、手に釣った魚(これで薬をこしらえる)、そしてガブリエル。

_TobiasandtheThreeArchangels(c1470).jpg)

Francesco Botticini (1446-97), Tobias and the Three Archangels (c. 1470)

左から、すかしたミカエル、犬、ラファエル、トビアス、そしてちょっとやる気のなさそうなガブリエル。この、ボッティチーニの絵で、左端の剣と玉をもっているミカエルのモデルはレオナルド・ダヴィンチだということになっています。

剣をふるった、勇猛なミカエルの図は多いです。一番有名なのはグイド・レニの絵かも――

.jpg)

Guideo Reni 〔2010.9.9訂正〕(1575-1642), The Archangel Michael (c. 1636)

ミカエルは竜とか堕天使とか悪魔とか踏みつけにします。ムカデを踏んでる絵はみつかりませんが。

いっぽう、ジャンヌ・ダルクの夢にあらわれたのがミカエルだということになっています。これがなかなかおもしろいです。

-6a9b2.jpg)

Eugine Thirioin, Appearance of Archangel Saint Michael to Joan of Arc (c. 1876)

Jules Bastien-Lepage (1848-84), Joan of Arc

このバスチアン=ルパージュは、はい、ジュディーが読む『マリ・バシュキルツェフの日記』を書いた女流画家マリが恋していた画家です(記事「マリ・バシュキルツェフの日記 Marie Bashkirtseff's Journal」など参照)。ミカエルは半分透明みたいな霊的存在として描かれているように見えます。

.jpg)

Joan of Arc's Vision (Harpers, 1895)

////////////////////////////////////////

「天使の一覧」 Wikipedia <http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E5%A4%A9%E4%BD%BF%E3%81%AE%E4%B8%80%E8%A6%A7>

「ミカエル」 Wikipedia <http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%9F%E3%82%AB%E3%82%A8%E3%83%AB>

「ラファエル」 Wikipedia <http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%A9%E3%83%95%E3%82%A1%E3%82%A8%E3%83%AB>

「ガブリエル」 Wikipedia <http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%AC%E3%83%96%E3%83%AA%E3%82%A8%E3%83%AB>

Fra Filippo Lippi - The Complete Works <http://www.frafilippolippi.org/>

Edgar Allan Poe, "Israfel" audio@ AudioPoetry <http://www.archive.org/details/audio_poetry_50_2006>

Hervey Allen, Israfel: The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe (New York: George H. Doran, 1927), Vol. I etext@ Internet Archive <http://www.archive.org/stream/israfelthelifean006580mbp#page/n11/mode/2up>

Hervey Allen, Israfel: The Life and Times of Edgar Allan Poe (New York: George H. Doran, 1927), Vol. II etext@ Internet Archive <http://www.archive.org/stream/israfelthelifean006456mbp#page/n9/mode/2up>

The Book of Tobit: A Chaldee Text from a Unique MS. in the Bodleian Library, with Other Rabbinical Texts, English Translations, and the Itala. Ed. Adolf Neubauer. (Oxford at the Clarendon Press, 1878) <http://www.archive.org/stream/israfelthelifean006456mbp#page/n9/mode/2up>

"Book of Tobit (Tobias)" audio@ LibriVox <http://www.archive.org/details/tobit_ss_librivox>

新しい診療所の建設・続報、と古い診療所とウィーン万博の話など Swift Memorial Infirmary [Marginalia 余白に]

今日もニューヨークタイムズを広げていたら、昨日の記事(「古い伝染病棟と新しい診療所 The Old Contagious Ward and the New Infirmary」参照)の続報が載っていました。――

.jpg)

The New York Times (February 2, 1900), 2面.

VASSAR'S NEW INFIRMARY.

_______

Mrs. Atwater Doubles Her Gift Because of Higher Cost of Building.POUGHKEEPSIE, Feb. 9―Mrs. Caroline Swift Atwater of Poughkeepsie, an alumna of the class of '77, has doubled her original gift of money to Vassar College for a new infirmary, the rise in the price of building materials since the gift was made last June necessitating a larger expenditure than was at first anticipated.

Vassar was the first college in the world to establish an infirmary, having had one in the main dormitory since the founding of the college itself. The growth of the college, however, and the erection of new dormitories has made desirable a separate infirmary building, which Mrs. Atwater's generosity has furnished. This will be known as the Swift Memorial Infirmary, in honor of Mrs. Atwater's father, a member of Vassar's first Board of Trustees.ヴァッサーの新しい診療所

________

建築費の高騰によりアトウォーター夫人、寄贈額を倍にポーキプシー、2月9日.――ポーキプシー市のキャロライン・スウィフト・アトウォーター夫人は、昨年6月、ヴァッサー大学の新しい診療所のための資金の寄付を行なっていたが(夫人は77年の卒業生)、建材の価格の高騰により、当初見込まれていたより多額の出費が必要となったため、はじめの寄付金を倍増した。

ヴァッサーは診療施設をもった世界初の大学であり、大学創設時より中央棟の寮内に診療所をもっていた。しかし、大学の拡充にともなういくつもの新しい寮の建造によって、独立した診療棟が望まれており、アトウォーター夫人の厚意により建設の運びとなった。新しい診療所は、ヴァッサーの最初の理事会のメンバーであった、アトウォーター夫人の父親を記念して、スウィフト記念診療所と名づけられる。

2代目の学長の(といっても「塔 Tower」で書いたように、初代ジュウェットを次いで1865年の開学時に学長となった)レイモンドが、7年の大学運営を経て、1873年5月に、合衆国教育局の求めに応じて大学運営の報告書を提出したときに、学内の医療施設についてはつぎのように書かれていました。(この報告書は、さらに教育局長の要請により、その年のウィーン万国博覧会に、女性の教育についてのヴァッサーでの取り組みの報告のために本として出版されました。この万博のテーマ(モットー)は「文化と教育 Kultur und Erziehung [Culture and Education]」でした。)――

The executive head is the President of the college, whose duty it is to watch over all its interests, and to see that all laws and regulations prescribed by competent authority are carried out. He is specially charged with its discipline and with the moral and religious instruction of the students. The Lady Principal is the chief executive aid of the President in the government of the college, and the immediate head of the college family. She exercises a maternal supervision over the deportment, health, social connections, personal habits, and wants of the students. She is assisted by nine of the lady teachers, each of whom has immediate charge of one of the college corridors; and in matters of health she has the counsel of the "Resident Physician," who is a regularly educated medical woman, and who has under her direction a well-appointed infirmary and a nurse. [Vassar College. A College for Women, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y.: A Sketch of Its Foundation, Aims, Resources, and of the Development of Its Scheme of Instruction to the Present Time (New York: S. W. Green, 1873) 13-14 <http://www.archive.org/stream/vassarcollegeac01raymgoog#page/n22/mode/2up/search/inf>]

この箇所を読んで初めて知ったのですが、学長とは別に "principal" 校長さんがいて、それは女性で、健康面も含めた学生の生活・習慣その他もろもろを「母親」のように監督するのでした(「"maternal supervision" を行使する」)。学長のほうは道徳教育・宗教教育の側面に責任をもつようにも書かれています。この the Lady Principal の下に9人の女教師がいてそれぞれ "corridor" を受け持ち、健康については医学をちゃんと学んだ "Resident Physician" ――というから住み込みですね――が校長の相談役というか協力者としていて、この女性の校医は看護婦とともに診療所を指揮するという体制です。

/////////////////////////////////////

Weltausstellung 1873, Vienna [at ExpoMuseum] <http://expomuseum.com/1873/> 〔ExpoMuseum <http://www.expomuseum.com/> のなかのウィーン万博1873のページ(別にヴァッサーのことは書いてありませんが〕

学生数の増加とスウィフト診療所・補足 Swift Infirmary, Swift Recovery, Swift Hall [Marginalia 余白に]

補足。足が遅いといいますか、だらだら書いている感じがあるかもしれませんが、自分にとってブログのいいところは、呑み込んですぐ排出するみたいな、消化不良のままに勢いで書けること、あるいは(ときどきは)即興の思いつきを節足に、いや拙速に書きとめられること、なの、かもしれず、ご勘弁を願います。

思えば1890年代から1900年代はじめというのは、学生数の増加によりヴァッサー大学に「寮」がつぎつぎと建てられた時期でした。すなわち、『あしながおじさん』の大学のモデルになっているヴァッサー女子大学にジーン・ウェブスターが1897年秋に入学したときには、ストロング・ハウス Strong House (1893) とレイモンド・ハウス Raymond House (1897) という二つの寮がありましたが、さらに Lathrop House (1901) と Davison House (1902) が同じ意匠で建設され、4つの寮が二の字二の字の下駄のあと、という感じで、二つずつ向かい合って並ぶ。そして「塔」のモデルと想定される9階建てのTower をもった ジュウェット・ハウス Jewett House (1907) が、"North" として4つの寮に向かい合って北側に建てられます。

当初から全寮制だったわけで、Main Building は教室と寮が一緒になっていたわけです。そして、そこに古い診療所もありました。1900年に卒業生が新しい独立した診療所の建物を寄贈することにしたのは、確かに要望が高かったからだと思われます。ヴァッサーの学生数の増加については、なぜかコーネル大学の同窓会報 Cornell Alvmni News, Vol. 3, No. 12 (1900年12月12日(水))に、記事として載っています <http://www.ecommons.cornell.edu/bitstream/1813/3165/12/003_12.pdf>。――

左から2つ目のコラムの最後の段落の記事です。この記事は、この2年であらわになった"over-crowded condition" を解消すべく100人収容の新しい dormitory が建設される、という主旨ですが、名前は出てないけれど Lathrop House (1901) の建設のことをいってると思われます。で、最後の一文――"Strong Hall, which was built in 1892, and Raymond House, which was erected four years later, have always been taxed to their full capacity, as well as the accomodations in the main building, and at the present time there are 135 students living in lodging houses outside the college grounds." (1892年に建てられたストロング・ホールと、その4年後に建造されたレイモンド・ハウスは、メイン・ビルディング内の施設同様につねに満杯の使用状況で、現在、135人の学生がキャンパスの外の宿泊所に暮らしている。)

135引く100は35で足りません。そして案の定、というか、つづく1902年にDavison House が建てられることになります。

135人が住んでいた "lodging houses" というのがどんなものだったのか興味深いのですが、わからんです(ヴァッサー大学にとってはあまり誇れる歴史ではないかもしれず)。

(ついでながら、左のコラム下の5行の短い記事は、カリフォルニア大学学長の Benjamin Ide Wheeler が『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌に "Art in Language" という論文を書いた、というものですが、ベンジャミン・ホイーラー (1854-1927) はマサチューセッツ出身でブラウン大学を卒業した文献学者で、1899年から1919年までバークレーのカリフォルニア大学の学長だった人です。おそらくコーネル大学の教授もしていたので載っているのかもしれません。彼を記念した Wheeler Hall にUCバークレーの英文科も入っています。なつかしい。)

☆ ☆ ☆

スウィフト診療所について、ヴァッサーの同窓会報 Vassar, the Alumnae/i Quarterly, Vol. 105, Issue 3 (Summer 2009) の "Hidden Histories" 特集の記事に書かれていました <http://vq.vassar.edu/issue/summer_2009/article/fs_hidden_histories_summer09>。

それによると、"Swift Hall" というのは現在の呼称で、1941年に史学科が移ってきたのだそうです(これは、補足すると、新しいBaldwin Infirmary が前の年に建てられたからです)。もとは Swift Infirmary でしたが、昔の学生の呼び名としては "Swift Recovery" だったそう。「早い回復(=スグナオル)」ということばのシャレです。

推定20世紀初頭のSwift Infirmary, image via epodunk.com <http://www.epodunk.com/cgi-bin/genInfo.php?locIndex=1476>

推定21世紀初頭の Swift Hall, image via Vassar, the Alumnae/i Quarterly <http://vq.vassar.edu/issue/summer_2009/article/fs_hidden_histories_summer09>

こうして100年の時間をはさんだ2枚の絵を眺めていると、そのあいだに数知れぬひとびとがさまよっているさまが、1枚の絵を見る以上に、浮かぶようです。

ジーン・ウェブスターの父親による『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』の出版 The Publication of _Adventures of Huckleberry Finn_ by Charles L. Webster [Marginalia 余白に]

ジーン・ウェブスターが生まれた1876年にマーク・トウェイン Mark Twain [Samuel Clemens, 1835-1910] の『トム・ソーヤーの冒険 The Adventures of Tom Sawyer』が出版されたのは、ふたりの作家の(といってもウェブスターの側での)ささやかな奇縁として語られることがあります。『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』の出版社は、ハートフォードの Elisha Bliss, Jr. というひとの the American Publishing Company で、この出版社は1869年の出世作『赤毛布外遊記 The Innocents Abroad』からマーク・トウェインの作品を出版し、マーク・トウェイン自身も1868年からハートフォードに住んでブリス Jr. と交流していました。オリヴィア・ラングドンと結婚して2年くらいはニューヨーク州バッファローに住みますが、1874年にまたハートフォードに戻ってきて、ビリヤード・ルームのある豪邸を建てました。

その後、A Tramp Abroad (1880) の出版は American Publishing Company ですが、The Prince and the Pauper (1882)、The Stolen White Elephant (1882)〔短篇小説ですが単行本として〕、Life on the Mississippi (1883) はボストンの James R. Osgood and Company から出版されました。

そして1884年5月1日、もともと出版や印刷に興味をもっていたマーク・トウェイン自身が出資して出版社をつくります。マーク・トウェインは、1875年に姉パメラ (Pamela Ann Clemens Moffett, 1827-1904) の娘のアニー・モフェット (Annie E. Moffett, 1852-1950) と結婚して義理の甥となっていたチャールズ・ルーサー・ウェブスター (Charles Luther Webster, 1851-91) に出版社の仕事を任せ、Charles L. Webster and Company という名前の出版社がニューヨークで立ち上げられます。結婚翌年の7月に生まれていた幼いジーンを含むウェブスター一家はフレドニアからニューヨークに居を移しています。この出版社が最初に出した本が『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』(アメリカ版、1885年2月)でした。同じ1885年には南北戦争時の将軍U・S・グラントの自伝も出版し、数十万部を売るベストセラーとなり、一躍有名な出版社となります。

しかし、その後、企画の失敗(法王の手記とかヘンリー・ウォード・ビーチャーの手記とか、11巻本のアメリカ文学アンソロジー――これ、見てみたいのですが・・・・・・――とか)や、ウェブスターの体調不良もあって、1888年、マーク・トウェインは Fred[erick] J. Hall というひとに首をすげかえます(でも出版社の名前は変えず)。チャールズ・ウェブスターは仕事の行き詰まりと精神的な疾患で苦しみ、薬の多量の服用により1891年4月28日、フレドニアの自宅で亡くなります(このときジーン・ウェブスターは14歳)。

その後、出版社の経営は不振で、大金を投じたペイジ植字機の失敗もあり、マーク・トウェイン自身が破産してしまい、1894年にチャールズ・ウェブスター・アンド・カンパニー社は10年の短命でなくなります。マーク・トウェインは、ハーパー社とか、あるいはまたアメリカン・パブリッシング・カンパニーとかから作品を出版するようになりました。

☆ ☆ ☆

で、『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』のことを書こうと思っていたのですが、だいぶ前置きが長くなったので(でもつい、ジーン・ウェブスターのことを考えていたら書かざるを得なかったのです)、細部はつぎにまわして、でも少しだけ書いておきたいと思います。

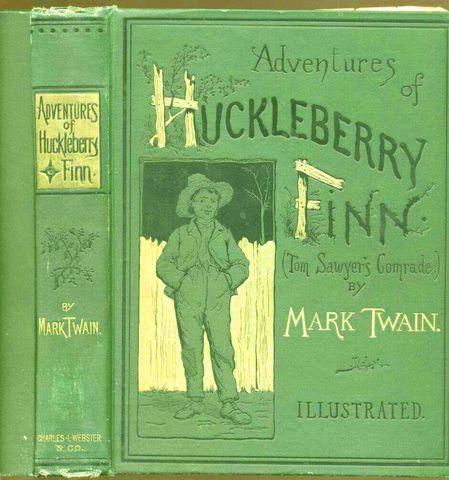

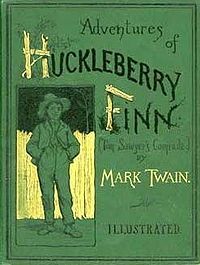

ウィキペディア(英語)の "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" にも載っているのは、つぎのおもて表紙です。――

これの背表紙の下のほうには "CHARLES L. WEBSTER & CO." と金字でしるされています。――

Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885)

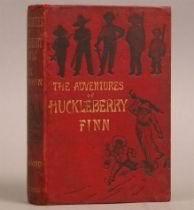

さて、ネットサーフィンしていたら、デラウェア大学図書館の特別収蔵品のページに、青色の表紙の初版が載っていました。――

.jpg)

image via "FOUR DECADES OF LIBRARY SUPPORT: Literature" University of Delaware Library, Special Collections Department <http://www.lib.udel.edu/ud/spec/exhibits/udla/lit.htm>

そして、説明は以下のようです。――

Mark Twain, 1835-1910.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: (Tom Sawyer's Comrade).... London: Chatto & Windus, 1884.Perhaps the best-known work of American literature, Huckleberry Finn has also been a source of great controversy over the years. The first edition of Twain's novel remains one of the great high spots of American book collecting.

『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』についての有名な話として、1884年に、誤って定冠詞 "The" を付してイギリス版を出版(上にあるようにロンドンのチャトー・アンド・ウィンダス社)、翌1895年に "The" をとってアメリカ版を出版ということがあります。アメリカ版の出版が遅れたのについては、E. W. Kemble の挿絵の1枚にワイセツなイタズラが加えられて、それを修正するのに時間がかかった、という事情があったとされていますが、ともかく、正しいタイトルは定冠詞のないもので、それは、リクツとしては、『トム・ソーヤーの冒険』のほうは冒険が完結しているが、『ハック』のほうは冒険が完結せず、まだこれからも続く、そのことと定冠詞の有無はかかわっているのだ、ということです(このリクツを最初に言った批評家はフィリップ・ヤングでした)。

いまはインターネットの時代で、わたしのような貧乏人にも初版テクストが電子的に入手可能です。で、Internet Archive を漁ると、英米両方の初版テクストが見つかりました(あー、しあわせ♪)。

.jpg)

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (London: Chatto & Windus, 1884) xvi+438, 32 (publisher's catalogue) pp. <http://www.archive.org/stream/adventureshuckl00unkngoog#page/n9/mode/2up2up>

title-591f6.jpg)

Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885) 366pp. <http://www.archive.org/stream/adventureshuckle00twaiiala#page/n9/mode/2up>

イギリス版のほうの電子テクスト (Google ブックス) は、残念ながらケンブルの挿絵を削除して見られないようにしています。版権の関係なのでしょうか。そして表紙もカヴァーしていません。

両方をパラパラめくっていると、まず本文第一ページの最初の挿絵にタイトルが含まれているのに気づきます。先にアメリカ版――

17.jpg)

Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885), p. 17

そしてイギリス版――![[The]AdventuresofHuckleberryFinn(Chatto,1884)xvi,1.jpg](https://occultamerica2.c.blog.ss-blog.jp/_images/blog/_73b/occultamerica2/m_5BThe5DAdventuresofHuckleberryFinn(Chatto2C1884)xvi2C1.jpg)

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (London: Chatto and Windus, 1884), pp. xvi, 1

イギリス版は、目次やイラストのリストの部分をローマ数字でページを振ってあり、本文のはじまりが第1ページです。アメリカ版は本文の始まりは第17ページ。両者はページ番号のみならず組版が異なっていることがわかります。それにしても、ケンブルの挿絵に組み込まれていた冒頭第一語の "You" まで切り取っているのはケシカランと思います("don't" で始まっている)。ムカデ図をはじめ著者のイラストを排除したグーテンベルクの『あしながおじさん』よりもひどいです。

しかし、げげげっ。アメリカ版を見ると、"The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" と定冠詞が入っているではありませんか(イギリス版の電子化ファイルが、たまたま "The" を切り取っているのはご愛嬌としても)。さらに、ページを繰ると、偶数ページの上部にタイトルが印刷されつづけています。

p2-3027f.jpg)

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (London: Chatto and Windus, 1884), p. 2

イギリス版に "The" が一貫するのはうなづずけるとしても、アメリカ版――

18-19.jpg)

Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885), pp. 18-19

左側18ページの上のマージンです。 THE ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN. と印刷されています。これは、最後のページまで同じです。

Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885), p. 366

そうすると、イギリス版とアメリカ版のタイトルの違いといわれるものは、まさにタイトルページだけなのかしら。

Google Books では見られないイギリス版の表紙を捜し求めました。それは、上のデラウェア大学図書館所蔵の青い表紙の本の背表紙の下の字が、どうも Chatto & Windus と書いてあるようには見えなかったということもあります。――

Mark Twain, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (London: Chatto & Windus, 1884)

赤でした。そして表紙のデザインは異なっていて、ちゃんと(w) "The" が入っていました。

ということで、少しだけ謎をはらませながらつづく~♪

///////////////////////////////////////

"Mark Twain, Publisher" ["Webster Company Publishing History"] <http://www.twainquotes.com/websterco.html> 〔www.twainquotes.com 内。チャールズ・L・ウェブスター社が1885年から1894年の10年間に出版した本のリスト〕

"A Rare Interview with Charles Webster" ["Charles Webster - short biography and interview"] <http://www.twainquotes.com/interviews/WebsterInterview.html> 〔同上〕

飯塚英一 「マーク・トウェイン最後の旅行記『赤道に沿って』の出版をめぐる経緯」 宇都宮大学『外国文学』 54 (March 2005): 1-13. pdf. 宇都宮大学学術情報レポジトリ <http://uuair.lib.utsunomiya-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/10241/357/1/KJ00004174273.pdf> 〔出版や経営や出資や投機についていろいろと書かれています。チャールズ・ウェブスターについては「厄介者」というふうに、まあマーク・トウェインの側に気持ちを投影して、書かれています。〕

チャールズ・L・ウェブスター社の『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』のちらしから本の装丁とかのはなしなど Flyers for Adventures of Huckleberry Finn [Marginalia 余白に]

「ジーン・ウェブスターの父親による『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』の出版 The Publication of _Adventures of Huckleberry Finn_ by Charles L. Webster 」のつづきで、「本の部分の英語名称メモ Names of Parts of a Book」の姉妹篇です。

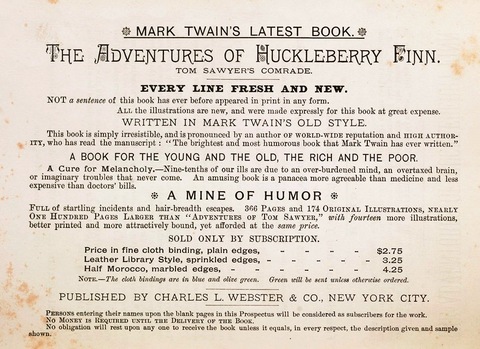

Wikimedia Commons の画像には、Broken Sphere というヒトによって Adventures of Huckleberry Finn 関係のチラシが4種あがっていて(<http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:BrokenSphere/Artwork/Books>)、それはいずれもヴァージニア大学の "Huck Flyers" ("West Coast Promotional Flyers")というページ(<http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/railton/huckfinn/hfoccidenthp.html>)のリンク先からとられているようです。記事本体は西海岸で販売を請け負った、サンフランシスコのサター・ストリートにあった the Occidental Publishing Company が作成したチラシや封筒についてのものですけれど、チラシの文章は最後のパラグラフ以外はチャールズ・ウェブスターがつくったチラシを踏襲していること("But the flyer's text, which is identical on both versions, was taken directly from the sales prospectus that Charles L. Webster & Co. created in 1884 (as you can see here and here). ")が説明されています。flyer フライアーというのはアメリカ英語で、「チラシ」、「ビラ」 (bill) のことです。

American Publishing Company もそうでしたが、マーク・トウェイン自身がつくった Charles L. Webster and Company も予約販売制の出版社でした。それで、エージェントがチラシをもって購買者を募ってあるく、あるいはチラシを郵送する、さらに、その前に(あるいはそれと同時に)エージェントを募集するということが行なわれたのです。ここにあがっているのは、購読者向けのものと、購読者を探すエージェント向けのもの2種x2です。

タイトルに "The" がついている件はここでは無視しますw。

下から10行目くらいに "SOLD ONLY BY SUBSCRIPTION" (予約購読のみ)と書かれて、そのあとに3種類の装丁が並んでいます。――

Price in fine cloth binding, plain edges, - - - - $2.75

Leather Library Style, sprinkled edges, - - - - - 3.25

Harf Morocco, marbled edges, - - - - - - 4.25

最初が布装(クロス装丁)。「エッジ」が「プレーン」というのは、「小口」(「「本」の部分の名称」参照)(複数であることからわかるように「天」と「地」と「前小口」の三方のふち」が「無地」(無彩色・無模様)、紙の色のままということです。これが2.75ドル。

ふたつめのは Leather (Library Style) と読んでいいと思うのですが、革装(ライブラリー仕様)。"Library Style" の起源について無知ですので、なんとなく方便としてアマゾンの "Bindings" の説明を含むページをリンクしておきます―― <http://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?ie=UTF8&nodeId=468558>。「エッジ」(小口)が「スプリンクルド」というのは、「パラ(掛け)」、霧染め模様にすることです。これが3.25ドル。

みっつめの、Half Morocco は半モロッコ革装(略 hf. mor.)。モロッコ革というのはヤギの皮をタンニン剤でなめした良質の皮革です。半 (half) は half binidng で、クロスの half binding(半クロス装 half cloth) もあれば革の half binding (半革装 half leather)もあります。表紙の全部を覆っている「総クロス(装) full cloth」 や「総革(装) full leather」が「丸装」「完表紙」で、 half は半分です。4分の1装 quarter binding(=背装) とか4分の3装 three-quarter binding というのもあります。marbled edges はマーブル(大理石)模様が小口にしつらえられているもの(「小口マーブル)。4.25ドル。

そうして、その下に、布装の色について書かれています――"NOTE―The cloth bindings are in blue and olive green. Green will be sent unless otherwise ordered." (注――クロス装はブルーとオリーヴ・グリーン。特に指定がなければグリーンを送付。)

これで、青と緑の2種類の表紙の謎が解けました。

しかし。この青と緑のクロス装、そして革装のあいだでも、テクストに異同があるらしいのです。それは、図書館に行ってカリフォルニア大学の全集版とか新しいハックの版とか見れば、たぶん諸テクストの校合(きょうごう collation)を行なって書いてあることかもしれませんが、いまは装丁との関係で、アリゾナ州スコッツデイルの古本屋さん、Charles Parkhurst Rarebooks のウェブサイトのマーク・トウェインのページを参照しておきたいです―― <http://parkhurstrarebooks.com/twainpg.htm>。

ここには2010年2月末日現在、総革装(9000ドル也)、ブルー・クロス(8500ドル)、グリーン・クロス(4800ドル)、そしてよくわからないけど写真を見ると背革に装丁しなおしたのかもしれないグリーン・クロス(2000ドル)の4冊のアメリカ初版が売られています。ABAA に属している古書店らしく、テクストの異同について記述があります。

ブルーのクロス装のものについて、これだけ1884年とする根拠は示されていませんが、特徴を列挙しています。―― "with the following early issue points; a) Illustration captioned "Him and another man: is erroneously listed as being on page 88. b). page 57, eleventh line from bottom reads "with the was"; c). There is no signature mark on page 161. d). Title leaf is tipped in, with copyright notice dated 1884 e.) Page 155 has final 5 lacking. f). Page 143, with "L" missing fron "COL." at top of illustration and "b" in "body" in line 7 is broken. g.) Page 28 is tipped-in." "issue" というのは、「刷」の意味だと思います。

そして、オリーヴ・グリーンのほうを、あとの「刷」としています――" A lovely copy with all the second state issue points, half-title, frontispiece, photo-gravure bust by Gerhardt, 366pp., 174 illustrations, bound in green pictorial cloth lettered and decorated in black and gilt, spine lettered in gilt and black, peach tinted endpapers. A superb copy, nearly fine with just a few spots of rubbing to joints and spine ends, no owner's names, plates or otherwise, internally very fresh, with the following issue points. p. [9]: "...Huck Decides to Leave..." is listed as part of the heading for Chapter VI (changed from "Decided". p. [13]: "Him and another Man" properly listed as at p. 87. p. 57, line 23: "with the saw" (corrected from "with the was"). frontispiece portrait: "Photo-Gravure" plate. title page: conjugate p. 143: "Col." at upper corner of plate includes the "l." p. 155: final "5" of page number in a different font (type slippage and replacement) p. 161: signature mark "11" missing. p. 283: corrected plate bound in."

"state" というのは版 (edition) は同じだけれども、出版までのあいだに訂正などがなされたりするときの「異刷」というやつです。このグリーンのほうが "second state issue" であって、ブルーのほうにあった誤りが訂正されている(典型的には57 ページの saw / was )。革装のものも "was" と直っておらず、ブルー・クロスと似た状態みたい――"The issue points are as follows: A). Illustrations captioned "Him and another man" is listed as being on p. 88. B). Eleventh line from bottom of page 57 reads, "with the was". C) No signature mark on page 161. D). Title leaf is integral with copyright notice dated 1884. E). Page 155 with final 5 absent. F). Page 143 with "1" missing from "Col." at top of illustration and "b" in "body" in line 7 is broken. G). Page 283 is integral in and has the curved fly which is known only in prospectuses and a few leather bound copies according to BAL." 〔この英語、とくに最後の文、つながりがヘンな感じ〕。

おもしろいです。まあ、1884年(つまりイギリス(&カナダ)版初版が出た年)に出るはずだったのが、アクシデントにより1885年2月に先延ばしになったという経緯とかかわるのかもしれませんが、直してない瑕疵があるテクストを最初から売っていいもんでしょうか。それはそれですか。

ところで、このあいだ「ジーン・ウェブスターの父親による『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』の出版 The Publication of _Adventures of Huckleberry Finn_ by Charles L. Webster」でリンクしたアメリカ初版――Mark Twain, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (New York: Charles L. Webster, 1885) 366pp. <http://www.archive.org/stream/adventureshuckle00twaiiala#page/n9/mode/2up>――は、青いクロス装のテクストだとわかりました。そして、誰の手によるものかわかりませんが、見返しに書き込みがあったのでした。――

こういう細かいのって、イラつくところもあるのですが、本好き(書痴・書狂など)としてはワクワクするところもあります。

半分と四分の三 Half and Three-Quarter Bindings [Marginalia 余白に]

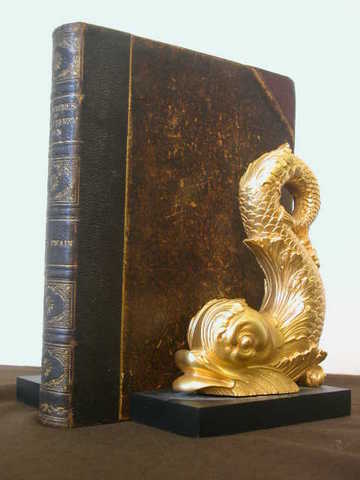

チャールズ・L・ウェブスター社の『ハックルベリー・フィンの冒険』の案内チラシ(prospectus, flyer)で "Half Morocco" とされている、いちばん高いアメリカ版初版が売られていた(すでに売れていたけど)のを見ました。――

image: Ziern-Hanon Galleries at GOAntiques.com <http://www.goantiques.com/detail,adventures-huckleberry-finn,321843.html>

本についての詳しい記述の半分くらいを引いておきます。――

FIRST EDITION, FIRST PRINTING, FIRST STATE. Square Octavo, original three-quarter brown publisher's morocco and marbled boards, marbled edges, gilt-decorated spine, marbled endpapers. First edition, first printing, first state of Twain's masterpiece, one of approximately 500 copies bound in publisher's three-quarter morocco binding. Copies of Huckleberry Finn were assembled haphazardly by the printer and there has yet to be agreement among bibliographers as to the priority of many points: This copy has all of the commonly identified first state points. First issue points include: On page 13, the list of illustrations has "Him and another Man" listed on page 88 (first state -- this was corrected later); Page 57 reads "with the was" (first state, this was later corrected to "with the saw"); page 9 with uncorrected "decided" (first state, this was later corrected to "decides"); Illustration on Page 283 with straight fly line (second state, curved line preferred); Copyright page dated 1884, as usual; signature number "11" on page 161 missing (first state); Final "5" dropped on page 155 (this was later replaced with a five of a different typeface); Dropped "I" in "Col," on page 143 and in "body" the "b" is broken. Frontispiece portrait shows sculptor's name and has the "Heliotype Printing Company" imprint (no priority is assigned because this was separately printed and tipped in).

書誌学者(文献目録編纂者)のあいだでもまだ議論があるようなことも書いてありますが、とりあえず異同のメモとして引いておきます。

気になったのは、"original three-quarter publisher's morocco"、"publisher's three-quarter morocco binding" というふうに、「ハーフ」ではなくて「四分の三」と記述していることです。このあと、マック・ドネルというひとの書誌からの引用があって、そこでも確かに「四分の三」となっています。――

"The relative rarity of the cloth and leather bindings is clear. Less than two weeks before publication, [the publisher] Webster announced that he was binding 20,000 copies in cloth, another 2,500 in sheep, and 500 copies in three-quarter leather. The remaining 7000 copies of the first printing were probably bound up in similar proportions. Leather copies dried out, cracked apart, and have survived in even fewer numbers than the original production numbers would promise" (MacDonnell, 35).

たぶんテキサス州オースティンの Mac Donnell Rare Books の店主で、ポーとかメルヴィルとかマーク・トウェインなどの初版本蒐集や文献目録作成で知られた Kevin B. Mac Donnell だと思うのですが、詳しいことは知りません。出版2週間前のチャールズ・L・ウェブスター社の広告ではクロス装を20000部、シープ革装を2500部、四分の三革装を500部となっていたそうです。

よくわからんのは、記述の最後のまとめには

[. . .] Maker: Mark Twain Title: Huckleberry Finn First Edtion, First State, Publisher's Leather Binding Style: Half morocco leather binding Type: half morocco leather binding

と、ふたたび「ハーフ」と書かれていることです。ハーフ装なのでしょうか、4分の3装なのでしょうか? そもそも半分と四分の三ってどうちがうのでしょう?

オックスフォード英語大辞典を見ると、"half-binding" は、"A style of binding of books in which the back and corners are of leather, the sides being of cloth or paper" と定義しています。背と角の部分が革で、サイド(なんて訳したら適当かわからず)は布または紙になっている本の装丁スタイル。そして、ちょっと意外だったのですが(無知だったとも言う)、もともとアメリカニズム (orig. U. S.) で、初出は1821年でした。用例のふたつめは1864年のウェブスター辞典のタイトルだけ出ていて、つまり、ウェブスター初版の改訂版でこの語がおさめられた、ということです。

"three- quarter" を見ると、2番のD に複合語と連語が並んでいるなかに、"three-quarter binding" があって、"a style of bookbinding having more leather than half-binding: see quot." (ハーフ装よりも多くの革のある本の装丁のスタイル――用例参照)と書かれています。用例を見ると、"*Three quarter binding is a very wide back and large corners. The sides may be of anything, paper, cloth [etc.]." という1897年の文章が引かれています。

勝手に推測するに、総革 (full leather; full binding) に対してつくられたハーフ装 (half binding) というのがそもそもきっちり半分ではなくてアバウトにつくられ、それと差異化すべく豊富に革を使ったものが四分の三装 (three-quarter binding) と呼ばれてつくられた、ということなのかしら。

神保町の老舗の古本屋の雄松堂のウェブサイトのなかにある、「新・古書への扉:ビアボーム「全集」-装丁を眺める」というページ(Net Pinus 64号: 2006/06/26)には、「この全集の装丁は全てが革ではなく、背と、背とは接していない角の部分が革で、残りはクロス(布)で覆われています。このような装丁を「半革装」(half bound)と言います。[写真5](*2)」という記述があります。

[写真5] image: 雄松堂 Net Pinus 64 <http://yushodo.co.jp/pinus/64/door/index.html>

注の2番は「実際に古書目録の中に出てくる表記は、使われている材料が明記されていることがほとんどです。モロッコ革が使われている場合にはhalf morocco(半モロッコ革装)、子牛革の場合はhalf calf(半子牛革装)と表記されています。また、背だけが革の装丁は quarter bound (背革装) と呼び、この場合にも、目録の中ではquarter calf(背牛革装)とかquarter morocco(背モロッコ革装)と表記されます。[写真6]」というものです。

このマックス・ビアボーム全集の装丁は、上の『ハック・フィン』と比べて、むしろ革の部分が多いようにさえ見えます。

本の厚みによって背に使われる革の量が変わるのだから、純粋に2分の1とか4分の3とか面積で決まっていてあまったぶんは表・裏表紙にもってくるとかいうのでなければ、それぞれアバウトで、4分の3も「ハーフ」の中に入れることもあるのでしょうか。同様に背革 quarter (leather) binding も厳密に4分の1とは思えません(わかりませんが)。

久永内科の久永光造さんの古書サイトのなかの「本の装丁について」 というページも楽しいです。ハーフ・モロッコ装の例としてあがっているなかにつぎの本があります。――

↓表紙は ハーフ モロッコ です マ-ブル紙とモロッコ皮との境界には金箔による金線が入っています マーブル紙は大理石様の模様以外に左上から右下にかけて かすかに うすい帯状の平行線が見えますが これは透かしマーブル紙といって非常に製作困難で マーブル紙としては最も高級なものです ハーフモロッコといってもこの程度のもにもなると へたなフルモロッコより好まれ高く評価されています

image: 「本の装丁 モロッコ革 マーブル紙 べラム 久永内科 久永光造」 <http://www4.ocn.ne.jp/~hisanaga/soutei.htm>

ということで、ハーフというのは(意味の)幅が広いのかなあ、と。

一生懸命、「四分の三」を明記している本を探すと、つぎのようなものが見つかりました。――

image: "Sample Offerings," Seneca Books, LLC. <http://www.senecararebooks.com/Sample_Offerings.html>

" Bound in three-quarter brown morocco, raised bands, and gilt lettering." と記述されています。

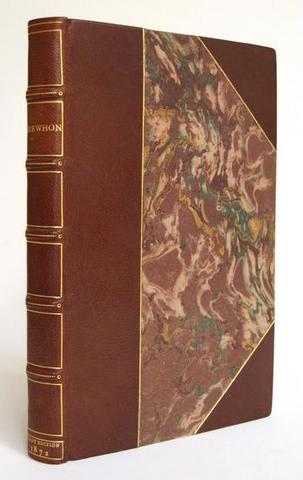

もうひとつ「ハーフ・モロッコ」の例――

image: Louella Kerr Books - Catalogues- <http://www.louellakerrbooks.com.au/cat113.htm>

やっぱり古本屋さんのサイトです。記述――

BUTLER, Samuel

Erewhon

London, Trubner & Co, 1872. First edition ppviii, 246, [2 blanks]. Roy 8vo, bound in half morocco with marbled boards by Sangorski & Sutcliffe, original brown cloth covers bound in at rear. A very fine copy

Sangorski & Sutcliffe というのは、1901年に創設された、イギリスの有名な装丁工房会社で、ウィキペディアにも載っています。1872年の初版本を装丁しなおしたのですが、オリジナルのクロス表紙は最後に綴じてある、ということです。

面積の計算をしてみようか、と一時は思ったのですが、すっかりやる気がなくなりましたw。

/////////////////////////////////////////

"History of Sangorski & Sutcliffe" <http://www.bookbinding.co.uk/History.htm> 〔Sangorski & Sutcliffe のHP。宝石を入れた有名な『ルバイヤート』や工房の写真あり〕

"Publications" Department of Preservation & Collection Maintenance, Cornell University Library <http://www.library.cornell.edu/preservation/publications/> 〔コーネル大学図書館〕

"September 2003 Fine Art and Antiques Auction Catalog" Aspire Auctions, Inc. <http://www.aspireauctions.com/auction23/3864.html> 〔quarter から half, three-quarter, full まで出品あり〕

ウェブスターが1年生のときのヴァッサー大学のカタログをまた見てみる Vassar Catalogue for 1897-1898 When Jean Webster Was a Freshman [Marginalia 余白に]

ジーン・ウェブスターが1年生のときのヴァッサー大学の便覧 The Thirty-Third Annual Catalogue of Vassar College をまた見てみました。寮のこととか書いてないかなあと。

68ページから始まる "The College and Its Material Equipment" という章の冒頭の概説と、一項目の Main Building の記述を書き写しておきます。――

THE COLLGE AND ITS MATERIAL EQUIPMENT. (大学とその設備)

The College is situated near the city of Poughkeepsie, which is on the Hudson River Railroad, 73 miles from New York. Electric cars run regularly to and from the city. The Western Union Telegraph Company has an office in the building.(大学はポーキプシー市近郊に位置する。ポーキプシーの駅はハドソン・リヴァー鉄道路線にあり、ニューヨークから73マイル(約120キロ)。電車が市とのあいだを往復して定期的に走っている。校舎内にウェスタン・ユニオン電報会社のオフィスがある。)

The College buildings comprise to the Main Building, a structure of five hundred feet long, containing students' rooms, apartments for officers of the College, the chapel, the F. F. Thompson library, and office; Strong Hall and Raymond House, residence buildings; the Vassar Brothers' Laboratory of Physics and Chemnistry; the Museum building, containing the collections of Natural History, the Art Galleries, the Music Rooms, and the Mineralogical and Biological Laboratories; the Observatory; the Alumnae Gymnasium; the Conservatory; houses for the President and for Professors; and various other buildings.(大学の建物は――メイン・ビルディング(本館)(幅500フィートの建物で、なかに学生の部屋、大学職員の住居、チャペル、F・F・トムソン図書館、事務室がある)/ストロング・ホールとレイモンド・ハウス(寮棟)/ヴァッサー・ブラザーズ物理化学実験棟/美術博物館(博物学の収集物と美術ギャラリー、音楽室、鉱物生物学研究室を含む)/校友体育館/温室/学長と教授の住宅/その他種々の建物からなる。)The Main Building (本館)

This building is warmed by steam, lighted with gas, and has an abundant supply of pure water. A passenger elevator is provided. Every possible provision against the danger from fire was made in the construction of the building. In addition to this there is a thoroughly equipped fire service, a steam fire engine, connections and hose on every floor, Babcock extingushers, and fire pumps.(この建物はスチーム暖房、ガス照明で、豊富な真水を貯蔵している。エレベーター備え付け。火災の危険に対するあらゆる可能な対策が建物の建造においてとられている。これに加えて、完全装備の消防隊[? どこに?]、蒸気式消防車[? どこに?]、各階ごとの連結器とホース、バブコック消火器、消防ポンプがある。〔よくわからんです〕)

The students' apartments are ordinarily in groups, with three sleeping-rooms opening into one study. There are also many single rooms and some accomodating two students. The rooms are provided with necessary furniture. The construction of the building is such that even more quiet is secured than in most smaller edifices. The walls separating the rooms are of brick, and the floors are deadened. (学生の部屋は通例複数室で、三つの寝室が一つの書斎にむかいあっている。個室も数多くあり、また学生二人にむく部屋もある。部屋には必要な家具が備わっている。これより小さな建造物以上にずっと静穏が確保されるように建物はつくられている。部屋を分ける壁はレンガ材で、床は防音にされている。) 〔Thirty-Third Annual Catalogue of the Officers and Students of Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, N. Y.: 1897-98 (Poughkeepsie: A. V. Haight, 1897), pp. 68-69 <http://www.archive.org/stream/annualcatalogue00collgoog#page/n717/mode/2up>〕

ということで、『あしながおじさん』2年生10月の手紙に描かれた3人の部屋割りはみごとにこの記述にあっていると思われます。

右下の Corridor (廊下)がどうやら線で示されているところがわかりにくいところかもしれません。たぶん Study だけが廊下に面していて、そこから個人のベッドルームに分かれるのでしょう(自信99パーセント)。

ちなみに、このあと1893年につくられた100人収容の寮、ストロング・ホールの記述があって、「一人部屋と、二人用の3室からなるスイートからなる」 (It is arranged in single rooms, and in suites of three rooms for two students)、と書かれています。あと、こちらには食堂の記述があって、建物の北の部分に2階分の天井の高さのダイニング・ルームがある (The dining room, the height of which extends through two stories, is at the north end of the building" と書かれています。女子学生のおしゃべりでうるさい食堂のモデルはこの建物のものなんですかね。

あと、冒頭の Electric cars というのは、いまはやりの電気自動車ではもちろんなくて(といってもガソリン自動車の前にすでに電気自動車は存在していましたけど)、train とは区別される street car というか tram というか、路面電車みたいなものだったのではないかと思います(今日アメリカには一部都市をのぞいて市街電車はなくなっていますけれど、第一次大戦前まではけっこうあったそうで)。 ちょっと調べてみないとわかりませんけれど。・・・・・・とりあえずウィキペディアの記事「アメリカ路面電車スキャンダル」参照。

あ、それとも the city というのはニューヨーク市のことを指しているのかしら。昔の路線図を調べてみねば。

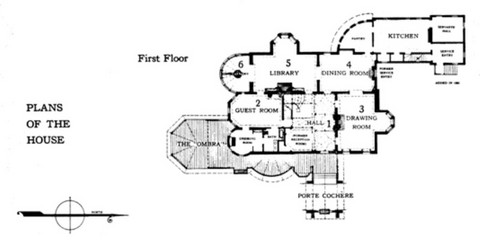

建物の向き (1)――建物の向きの指示は大学向きだったっていえるのかい Direction(s) of Buildings (1) [Marginalia 余白に]

マーク・トウェインのコネティカット州ハートフォードの家についての和栗了氏の論文「家のドアを開けないで」で自分は知ったのかと思うのですが、マーク・トウェインの家の玄関は東を向いているのだそうです。「マーク・トウェインの八角形をいれた家 Octagonal Shapes in the Mark Twain House」に孫引きした図面を見ると、精確なところはわかりませんけれど、なるほど、Mark Twain House の画像として多く見られるアズマヤ ("THE OMBRA") は南の方角で、玄関はほぼ真東(下の図で真下)にあるのだと了解されます。

さて、マーク・トウェインのことは専門でもないしよくわからんのですが、マーク・トウェインの姉の娘の娘のジーン・ウェブスター(ったって専門であるわけでもないですが)が、どうやらヴァッサー大学の Main Building (「本館」と訳していいものやらいまだ自信なし)に暮らしていたらしいことを、ここ数日の記事で、確認したうえでの話です。

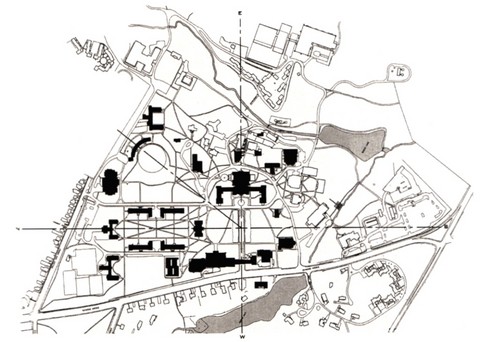

さっきから探していて見つからないのですが、ヴァッサーの校舎を中心とした建築ガイド本を、ついこのあいだ衝動買いして、自分が過去にかかわってきた日本の大学のいずれに対するよりも深い知識を外国の大学にさらにもちつつある今日この頃なのです。それで、文章を参照(適当な記憶はあるんですけど)するのは先送りにして、図版だけ引いておきます。――

based on the top figure "Diagram of buildings located along the cardinal axis" of page 31 of Vassar College: An Architectural Tour (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004)

図の真ん中の大きなインベーダーみたいなのが Main Building です。ここは1865年に完成した最初の大学校舎です。えーと、この図は上が東、左が北、ですけれど、ちょうど南北のラインが通っている北の端にある小さなインベーダーが、1907年建造のJewett House です。後ろの●がタワーです(「塔 Tower」参照・・・・・・ほんとは丸くないです。純然たる八角形でもないです)。

正門は縦の、東西のラインの下の、つまり西の下のほうの、黒いかたまりの細くなっているところですが、とりあえず、大きいインベーダーが真西を向いていること、つまり本館の正面は西であること、は了解されると思います。

謎をはらみつつ自分でも混沌とした頭でつづく~♪

追伸。半分で拙速に出すのは、夕方まちがってほんの数行で一時公開したためでございます。まことにすいませんでした。

建物の向き (2)――建物の向きの指示は大学向きだったっていえるのかい Direction(s) of Buildings (2) [Marginalia 余白に]

昨晩ののつづきです。

本、見つかりました。Karen Van Lengen and Lisa Reilly, Vassar College: An Architectural Tour (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004). 引用します。――

The positioning of the campus's first structure, Main, was controversial. Vassar had wanted to align it with Raymond Avenue but President Jewett convinced him that placement along the cardinal points would serve as an "educating force," and so Main was oriented directly west, toward, but not in view of the great Hudson River. This early decision to place the college within its larger geographical context was to remain an important force in the future development of this section of the campus, associating the college with its larger habitat―the Hudson River Valley. All of the buildings located on the flat plain near Main follow this initial alignment. Later, as the college expanded, building along the Casperkill and Fonteyn Kill would be located in relation to the local landscape, rather than on the established axis, and their siting would follow the topography of the creek beds. These two contiguous systems are today seamlessly joined by the landscape plan that has evolved incrementally and has been largely created by the Vassar community itself. (30)

(キャンパスの最初の校舎、メイン(本館)をどの場所に置くかについては議論があった。ヴァッサーはレイモンド・アヴェニューの通りに沿うように望んだが、ジュウェット学長は、方位にあわせて建てることで「教育の力 educating force」として作用するとヴァッサーを説得した。結果、メインは真西を向くこととなり、ハドソン河のほうを向いてはいるけれども河が見える位置にはない。大きな地理的コンテクストに大学を位置づけるというこの最初期の決定は、その後のキャンパスのこの部分の展開に影響力をもって残りつづけることとなった。大学は、ハドソン河ヴァレーという大きな環境と関連付けられたのである。メインのそばの平地に位置する建物はすべてこの最初の配列にならった。のちに、大学が拡充し、キャスパーキルとフォンテイン・キル〔kill というのは、川、水路です〕に沿って建物がつくられたときには、定着した軸線ではなくて、風景との関係で配置されるようになった。つまりクリークの川床の地勢に従ったのである。この2種類の体系は、主としてヴァッサーのコミュニティー自身によってつくられ進展してきた風景計画によって、今日ほころびなく結び合わさっている。)

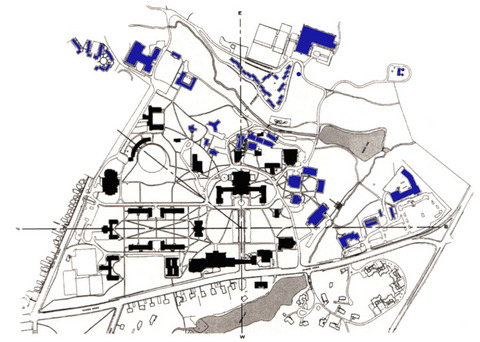

ということで、東西南北という方位にあわせた建造と、水系を中心とする自然の風景にあわせた建造が、混在している、ということです。

このあいだ古いPhotoshop 2.0 が無事インストールできたので、ひまにまかせて色づけしてみました。青いのが後者の建築です。黒いのは東西南北の軸に沿った建物群。ふつうの地図と違って、上が東で左が北です。――

Figure II, based on the top figure "Diagram of buildings located along the cardinal axis" of page 31 of Vassar College: An Architectural Tour (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004)

グレーの箇所は川と湖です。メイン・ビルディングの右上にあるのが Sunset Lake、下(西)にあるのが Vassar Lake (元の名は Mill Cove Lake)。ヴァッサー湖と大学のあいだにある広い道が Raymond Avenue です。サンセット湖から北東にのびている川がキャスパーキル、そしてフォンテイン・キルの元の名は Mill-Cove Brook といったので、それはヴァッサー湖とつながっているクリークなのでしょう(自信50パーセント)。ハドソン河はどこにあるかというと、図の下(西)を南北に流れています。下の地図(上が北)だと南北にハドソン河が流れていて、東に大学があります。

目測で、大学からハドソン河まで2マイルは離れていると思われます。

さて、上に引いた文章でよくわからないのは、創設者のヴァッサーの考えに反対して方位に従った建造を進言した初代学長のジュウェットは、南北に流れる大河ハドソンとの関係で校舎を位置づけたのか(なんだかそういうふうな流れで上の文章は解釈しようとしているように見えます)、それとも、それはそれとして、真西とか真東とか、方位を最重要としたのか(そういうふうに自分は読みたいのですが)、です。ちなみにジュウェットの名を冠した5番目の寮は当初 "North" という名でしたが、図の南北方向(水平方向)の軸の上に、ということは、東西の中心として位置づけられているように見えます。

The Hudson River Valley, image via "Hudson Valley," Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hudson_Valley>

☆ ☆ ☆

建物の方位で、ヨーロッパ文化において伝統的に際立っているのは、キリスト教の教会です。すなわち、祭壇は東を向くように建造され、教会堂の入口は西でした。太陽がのぼる東を向いて礼拝するのは異教の習慣をいれたのだ、という批判(?)がなされうるかもしれませんが、キリスト教会は、「主の栄光は東から」(「エゼキエル書」43章)を典拠として正当化した、とされています。

はじめ、はじめチャペルがメイン・ビルディング内にあったということと関係するのかなあ、とも思ったのですけれど、ジュウェットのいう「教育の力 educating force」は、どうも純粋に宗教的なものとも思えないような気もします。それとも結局のところ宗教的なものが背後にあったのかしら。

『あしながおじさん』3年生の4月の末ごろの手紙に、夜明け前に2マイル歩いて山(One Tree Hill 一ツ木山?)に登り、太陽サンサンご来光を仰ぐエピソードが出てきます。ひそかな太陽神崇拝があったのでしょうか(w)。

226-e3ff3.jpg)

Daddy-Long-Legs (Century, 1912) 226

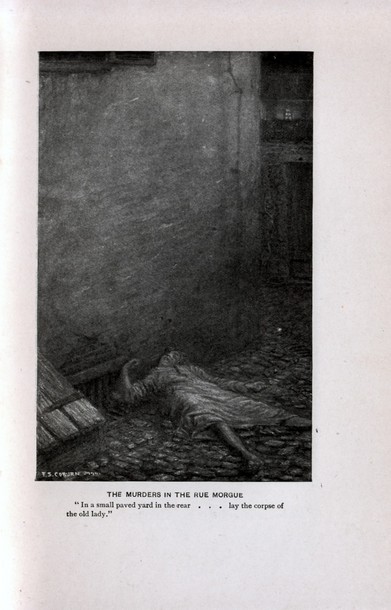

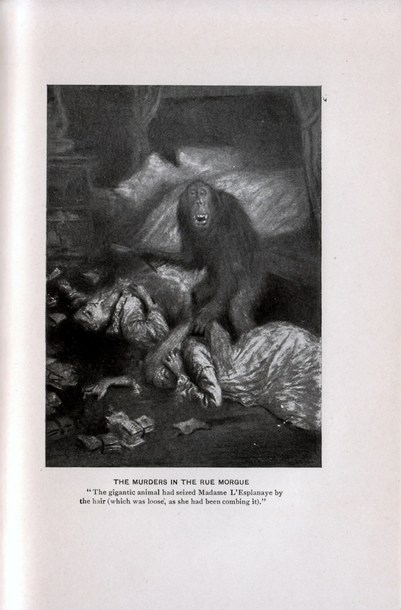

写真家アルヴィン・ラングドン・コバーンについての覚え書 A Note on the Life of Alvin Langdon Coburn [Marginalia 余白に]

〔いちおう「拝啓着物柱様 Dear Clothes-Pole」のあとの「シルバニアファミリーのものほしセット――拝啓クローズ・ポール(着物柱)様、パート2 Dear Clothes-Pole, Part 2」に載せた写真家コバーンのものほしざお写真から派生したものです。〕

アルヴィン・ラングドン・コバーン Alvin Langdon Coburn, 1882-1966?はアメリカ生まれの写真家です(最晩年にイギリスに帰化)。ボストンのシャツ製造会社の息子に生まれ、7歳のときに創業者の父親が死去、1890年に母方の親戚のいるロサンゼルスに行ったときに、おじさんたちからカメラをプレゼントされ、少年はたちまち写真に魅了されます。1898年、既に国際的に名の知られていた親戚(いとこ)のF. Holland Day?を訪問し、写真の技術を認められます。1899年、母親とロンドンへ移住。そこには王立写真協会 Royal Photographic Society?に招聘されていたDay がいて、アメリカの写真家たちの作品を集めた展覧会の企画の仕事をしていました。その展覧会に若干17歳のコバーンの作品も展示されることになり、華々しいデビューを飾ります。当時もっとも尊敬されていた写真家である Frederick H. Evans, 1853-1943?の目に留まり、エヴァンズらが創設していた写真家グループ Linked Ring の展覧会にも出品します。エヴァンズという人は、教会建築などの写真で有名ですが、ビアズリー (1872-98) の肖像なども撮影しているひとです。――

.jpg)

Frederick H. Evans, Aubrey Beardsley (1894) ![]() Estate of Frederick H. Evans

Estate of Frederick H. Evans

その後、国際的に活躍し、有名なスティーグリッツの雑誌 Camera Work に掲載されたり、スティーグリッツによって個展を開いたり、1910年のニューヨーク州バッファローのAlbright-Knox Art Gallery での展覧会のあと、アメリカ国内を旅行してグランド・キャニオンやヨセミテなどで「自然」の写真を撮ります。1911年、ニューヨークで街の写真を撮影、1912年には写真集 New York を出版(これにおさめられた『タコ The Octopus』が彼の最も有名な写真のようです)。1912年、ボストンの Edith Wightman Clement という女性と結婚。

コバーンというひとが個人的に興味深いのは、1916年ごろからの神秘主義や神秘思想への傾倒です。1916年という年は、いっぽうで詩人のエズラ・パウンドと知り合い、パウンドの影響を受けて、ヴォーティシズムの写真における実践を試みた年です。1913年、パウンドによって Vorticism の名称を与えられたイギリスの前衛的な美術運動は、1914年に機関誌 Blast を創刊したグループ自体は、1915年の第2号の刊行とロンドンのドレ・ギャラリーでの展覧会ののち解散していますが、パウンドはコバーンに新たな可能性を見たのかもしれません。3枚の鏡をはめこんだ機材を用いて撮られたコバーンの写真はパウンドによって Vortograph と呼ばれました。

コバーンは abstract photgraph というコトバのでてくるエッセイ "The Future of Pictorial Photography" を1916年に書いて、イメジの外側に指示対象をもつのではなくて、イメジの下にある形態や構造を強調することを説いており、パウンドとの出会いは、コバーンの「抽象写真」に影響を与えたわけでしょうが、同じ年に、写真家のジョージ・デイヴィッソン George Davison, 1854-1930?と親しくなってもいます。デイヴィッソンは Linked Ring の創立にかかわったひとでもあったのですが、その後イーストマン・コダック社の管理職になりながら、博愛主義者として社会改良運動に傾倒してアナキストと関係をもったために会社を追われます(最終的には1912年)。それはそれとして(ちょっと『あしながおじさん』のなかの philanthropy や socialism を思わせるのですが)、デイヴィッソンがコバーンに与えた影響は、彼が神智学者でもあった(あとはおまけにフリーメイソンでもあった)ところで、コバーンは神秘思想やドルイドの研究にのめりこんでいくのです。

1920年ごろにはフリーメイソンのなかで Royal Arch Mason の位階にのぼっています。さらに、薔薇十字運動の流れをくむと称する、スコットランド起源の?Societas Rosicruciana に入会。Societas Rosicruciana というのは、フリーメイソンの第三位階である親方 Master Mason のみが加入できる交友組織です。1923年、the Universal Order という秘密結社の人物と出会い、その後の人生に決定的な影響を受けたといわれています。the Universal Order というのは季刊誌 The Shrine of Wisdom: A Quarterly Devoted to Synthetic Philosophy, Religion & Mysticism (これの1920~30年代のバックナンバーを Kessinger が復刻しています)刊行しているくらいですから、めちゃくちゃ秘密の結社だとは思いませんけれど、この人物は謎のままです。コバーンはさらにフリーメイソンの歴史や古代祭儀やオカルトの研究に没頭するようになり、多数の講演活動や調査旅行を行なったりします。1927年、Gorsedd (ゴーセズ:古代ウェールズにおける吟遊詩人とドルイド僧の祭を19世紀に復活させた集会)において名誉第三級吟遊詩人となり、ウェールズ名、Maby-y-Trioedd を取得。1930年ごろには写真に対する興味はほとんどなくなっており、過去は無意味と考えて、ネガなどを処分すると同時に、コレクションを王立写真協会に寄贈。1957年10月11日、結婚45周年の日に妻のイーディスが逝去。1966年、北ウェールズの自宅でコバーン死去。享年84。

コバーンの生涯をふりかえって、神秘主義への傾倒でちょっと類推関係を感じるのは、アメリカの作家のハムリン・ガーランドやウィンストン・チャーチル(同名の英国首相のいとこの)なのですが――神秘思想に傾倒する作家は多いのですけれど、それによって過去の自分の芸術的営みを無意味化する身ぶりが気になるのです――、話が錯綜するので、またそれは別の機会があれば、と思います。

タコに落ちる摩天楼の影 The Shadow of the Skyscraper on the Octopus [Marginalia 余白に]

1912年に出版されたアルヴィン・ラングドン・コバーンの写真集 New York におさめられた『タコ The Octopus』(リンク先は Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History; 別url <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pict/ho_1987.1100.13.htm>)は、冬の雪に覆われたニューヨーク、マンハッタンのマディソン・スクウェア・パーク Madison Square Park を俯瞰的に切り取ったものです。

.jpg)

"Alvin Langdon Coburn: The Octopus (1987.1100.13)". In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. <http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/pict/ho_1987.1100.13.htm>

タコというと、19世紀後半にアメリカに広がった鉄道網をタコにたとえた作家フランク・ノリスの The Octopus が有名ですが、コバーンのタコは公園のセンターとそこから放射状に延びる道の様子をタコに見立てている模様です。

しかし画面の左半分に巨大な影が落ちています。ニューヨークという都会の摩天楼の影です。雪は空から降ってくる。摩天楼 skyscraper というのはその空を引っ掻く (scrape) ような高さを誇る建物のことです。

ウィキペディアで「摩天楼」を調べようとすると「超高層建築物」 <http://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E8%B6%85%E9%AB%98%E5%B1%A4%E5%BB%BA%E7%AF%89%E7%89%A9>というミモフタモナイ名前の項目に飛ばされるのですが、そこには、歴史的なリストが挙がっていて、ニューヨーク関係では、リストのトップにあがっている1873年の8階建て43m のエクイタブル生命ビル (1912年解体)、1890年の20階106mのニューヨークワールドビル(1955年解体)、1894年の18階建て106mのマンハッタン生命保険ビル (1930年解体)、1899年の30階建て119mバークロービル、そして世紀が変わって1908年の47階187mのシンガービル (1968年解体)、1909年の50階213mのメトロポリタン生命保険会社タワーというのが、1912年の時点(ちなみにたまたまこの年は『あしながおじさん』出版の年でもあります)でニューヨーク市に建っていた「摩天楼」群だということがわかります(最初の8階建て程度のものはその後たくさんつくられたでしょうから、歴史的な意味合いで載っているのでしょう)。

で、最後のメトロポリタン生命保険会社タワー (Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower) がマディソン・スクウェアに影を落としているのではないかな、と見当をつけて、現代の地図を見てみました。――

A地点が、40°44′28.49″N 73°59′14.76″W / 40.7412472°N 73.9874333°W

| |

にある、Met Life Tower です。なんか緑がだいぶ多くなっています(季節の問題ではおそらくなく)。

このタワーは、1893年完成の11階建ての建物に付け足された建造物で、ヴェニスのサン・マルコ広場の鐘楼(カンパニーレ)を模してつくられ(つーことはバークレーのセイザー・タワーと同じですね――「March 18 バークレーのセイザータワー The Sather Tower in UC Berkeley」参照)、時鐘というか鐘楼というか鐘塔としては鐘ではなくて4面に直径8mの時計をはめこんでいます。

メトロポリタン生命保険会社タワー (Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower), "Metropolitan Life Bldg., Manhattan, New York City, in 1911," image via Wikipedia <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Met_life_tower_crop.jpg>

1911年ごろのようす。

なんだか、地図が違っているような不安がありますけれど、ともかく、摩天楼の影はこのタワーであると思います。

タコというのは欧米人にとっては悪魔のイメジということはよく言われてきましたけれど、そういうのを引きずっているのかは不明です。しかし、海のイメジと空のイメジがぶつかっているということは言えるのでしょう。そして水平的に広がっていったノリス的なタコ(鉄道)に対して、垂直的に広がる人間の野心みたいなものを映しているのかもしれないな、と思いました。

高さ213mというのは700フィートです。1913年の Woolworth ビルの建造まで、このタワーが世界一の高さの建造物だったのだそうです。

/////////////////////////////

メモ的 urls―

Frank Norris, The Octopus: A Story of California (1901) e-text <http://www.archive.org/stream/octopus00norr#page/n5/mode/2up>

Herman Melville, "The Bell-Tower," The Piazza Tales (1856) e-text <http://www.archive.org/stream/piazztales00melvrich#page/400/mode/2up/search/bell+tower>

「「時計」の文学論 - 教授のおすすめ!セレクトショップ」 <http://plaza.rakuten.co.jp/professor306/diary/200911210000/> 〔 釈迦楽先生のブログ2009.11.21 〕

「今週の本棚:富山太佳夫・評 『ワシントン・アーヴィングと…』/『時の娘たち』 - 毎日jp(毎日新聞)」 <http://mainichi.jp/enta/book/hondana/archive/news/2005/08/20050807ddm015070156000c.html> 〔書評 2005.8.7〕

岡村仁一 「「平地からは見えない光景」――ハーマン・メルヴィルの「鐘塔」について」 『新潟大学言語文化研究』pdf. <http://dspace.lib.niigata-u.ac.jp/dspace/bitstream/10191/6000/1/06_0001.pdf>

モーリス・ブランショ 「メルヴィルの魔法」(『日曜風景』誌連載、<本>、モーリス・ブランショ、1945年12月16日、3頁所収) <http://www.geocities.co.jp/CollegeLife/4761/Melvillepaysdimanche.htm>

風間賢二 「オートマトンが怖い!」 文学と科学のインタフェイス2) 季刊 環境情報誌ネイチャーインタフェイス No. 5 <http://www.natureinterface.com/j/ni05/P90-91/>

カガンボ、ガガンボ、アメンボ [Marginalia 余白に]

以前、『あしながおじさん』のアシナガオジサンがガガンボではなくてザトウムシ(メクラグモ)であることを論証wしようとしたときに(記事「ダディーロングレッグズ (1) Daddy-Long-Legs」&その改増版)、既訳を並べたなかで、新潮文庫の松本恵子の訳文を、つぎのように書き写しました。――

松本恵子 (1954) は「足長とんぼ」と「あしながおじさん[ルビ: ダディ・ロング・レグズ](割注: *かがんぼ [sic])」。

厨川圭子なんかは「大蚊」にルビで「ががんぼ」と振っていたのでした。――

厨川圭子 (1955) は「大蚊[ルビ: ががんぼ]」と「本物の「あしながおじさん」(大蚊[ルビ: ががんぼ)」。

松本恵子の「かがんぼ」は誤植かと思っていたのですが、まもなく「かがんぼ」がもともとで、「ががんぼ」はそれがなまったものらしい、と知りました。

それでも、詳しく調べることはせずに、「かがみ坊」のなまったものかな、と自分勝手に思っていました。「あめん坊」と同じ坊主の仲間かとw。

ところがっ。『大辞泉』は語源について「《「蚊ヶ母(かがんぼ)」の意から転じた語》」としています。蚊の母か。でかいからか。

『大辞林』は同義語として、「カノオバ。カガンボ。カトンボ。」を並べています。ひとつめの「カノオバ」というのは「蚊のおば(叔母・伯母・小母)」(さん)か、「蚊の姥・祖母」でしょうから、坊じゃないのね。しかし、「カノオバ」における助詞の「の」や「オバ」に比べて、「カガンボ」の「が」や音読みの「ボ (母)」――ふつうに母のことを「ボ」とは呼ばんやろう、日本人は――はなんかカタクって、不自然な感じがしなくもないです。まあ、古語のころから呼称があったということか。でかい辞典を調べてみようとは思います。・・・・・・

そして、アメンボのほうも気になって調べました。こちらも勝手な個人的連想では、雨のあとの水たまりにどこからともなくやってきてスイスイと浮かんでいる姿が幼いころの記憶にあり(東京の国分寺界隈、遠い目)、「雨」がらみとばかり思っていました。

ところがっ。アメンボは飴坊で、雨ん坊ではないみたいなのでした。アメンボ(アメンボウ)はカメムシに近いところがあって、「外見は科によって異なるが、翅や口吻など体の基本的な構造はカメムシ類と同じである。カメムシ類とはいかないまでも体に臭腺を持っており、捕えると匂いを放つ。「アメンボ」という呼称も、この匂いが飴のようだと捉えられたことに由来する。」(ウィキペディア「アメンボ類」)。ふーん。カメムシ類とは「いかないまでも」カメムシ類と同じか。捕まえたことがなかったからか、そんな連想はぜんぜん働きませんでした。

ちなみに英語だとアメンボは water strider とか water spider とかいくつか呼び名があるみたいです。

ウィキペディアは漢字「水黽、水馬、飴坊」を挙げているけれど、「アメンボウ」の読みは示しておらないです。広辞苑で「あめんぼう」を見ると「飴ん坊」で、①棒状につくった飴菓子、②「つらら」の異称。たれんぼう、と書かれています。たれんぼう。あまえんぼう。さびしんぼう。うろたえて一つ前の「あめんぼ」を見ると、漢字は「水黽」しか挙げていないくせに、「飴のような臭いを出す。・・・・・・アメンボウ。カワグモ。水馬。」と書かれておる。

ガガンボのほうは――「【大蚊】(カガンボとも)ハエ目ガガンボ科の昆虫。カに似るがはるかに大きく、血を吸わない。脚は長くもげやすい。・・・・・・カノウバ。カノオバ。カトンボ。」

「カノオバ」に加えて「カノウバ」が挙がっています。ウバが乳母か姥かはわかりませんな。

で、ガガンボウというつづりは挙がっていないけれど、WEB で検索すると、うちの地方ではガガンボウと呼びます、みたいな発言がけっこうあって、アメンボ/アメンボウみたいにガガンボ/ガガンボウという両方の呼び名があるみたい。仮に「蚊が母」(が=の・・・・・・我が母みたいに)という語源説が正しいとして、そのボ(母)はボウ(坊)にジェンダー転換してしまうってことでしょうか、民衆の想像力のなかでは(そんなおおげさなものではない)。

ポンチョ・雨ん坊 #3300

特価:4,050円(税込) フクヨシ特価:3,000円(税込) image via ユニフォームのフクヨシ

<http://store.shopping.yahoo.co.jp/e-fukuyoshi/470.html>

天の父と地の父――『緋文字』のばあい(1) (母と娘の会話) Your Heavenly Father and Your Earthly Father in _The Scarlet Letter_: A Conversation Between a Mother and a Daughter [Marginalia 余白に]

〔記事「『あしながおじさん』における神 (第3のノート) 」と「天にまします我らの父――主の祈り Our Father in Heaven: Lord's Prayer」につづく記事「父なる神 God the Father」につづく記事「天の父と地の父(母と娘の会話)――『若草物語』のばあい Your Heavenly Father and Your Earthly Father in _Little Women_: A Conversation Between a Mother and a Daughter」に並ぶものです〕

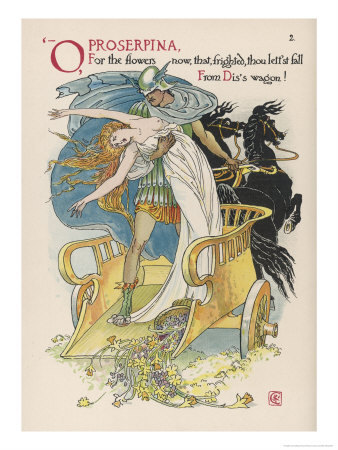

ナサニエル・ホーソーンの代表作『緋文字』 (1850) は17世紀中ごろのアメリカ植民地を舞台にした歴史ロマンスで、独身の牧師と姦通を犯して女の子パールを産んだ若い人妻のへスター・プリンが赤ん坊を抱いてさらし台に立たされているところから物語は始まり、7年間ぐらいのスパンを全24章でまったりねちねちと描いて、完全な善玉・悪玉、100パーセント好意的に感情移入できるヒーローもヒロインもいない、暗く曖昧な作品となっています。

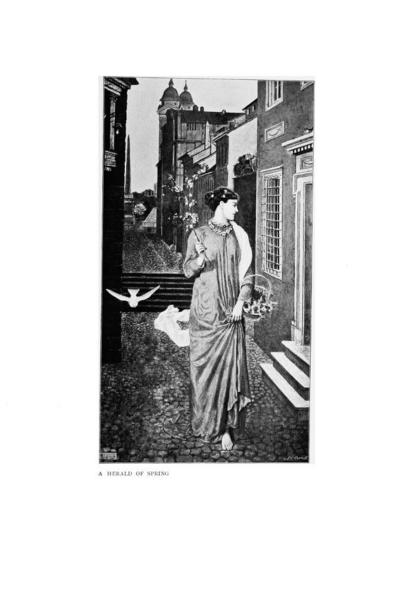

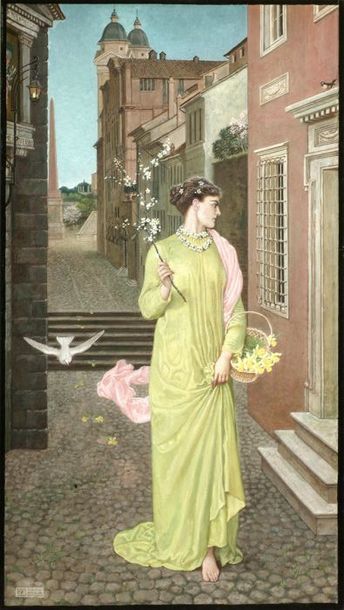

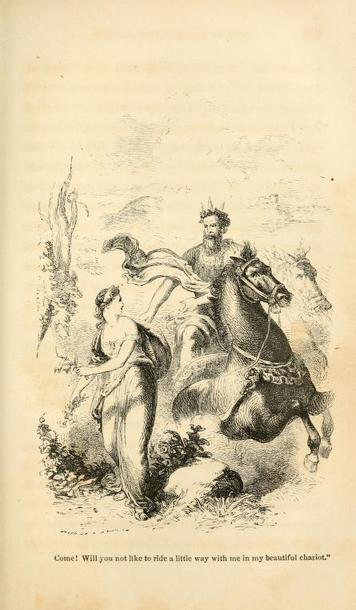

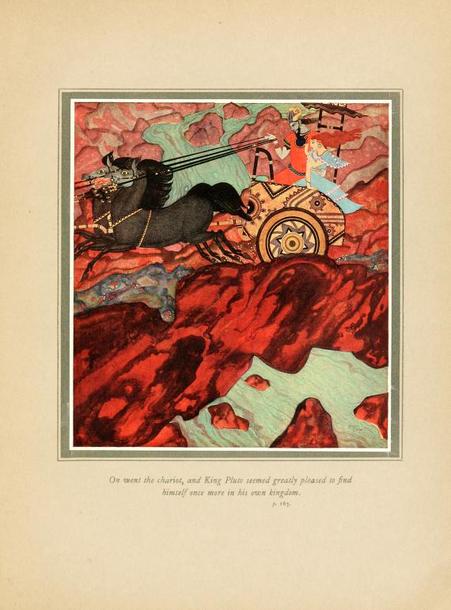

Frederick C. Gordon, illust. The Scarlet Letter (New York: Frederick A. Stokes,1893), p. 70――赤ん坊のパールを抱き、胸にAdultery (姦通)の頭文字の A の刺繍をつけてさらし台に立つへスター

第6章「パール」――

パールをじっと見ていると、へスター・プリンは手にしている針仕事を思わず膝に落として、隠しておきたいと思う苦しみが言葉とも呻きともつかぬ声となって、泣きさけぶことがよくあった。「おお、<天にまします父>よ、もしいまも<あなた>がわたしの<父>でいてくださるのならお答えください。わたしがこの世に生み落としたこの子供は何者でございましょう。」・・・・・・

(Gazing at Pearl, Hester Prynne often dropped her work upon her knees, and cried out with an agony which she would fain have hidden, but which made utterance for itself betwixt speech and a groan—"O Father in Heaven—if Thou art still my Father—what is this being which I have brought into the world?" And Pearl, overhearing the ejaculation, or aware through some more subtile channel, of those throbs of anguish, would turn her vivid and beautiful little face upon her mother, smile with sprite-like intelligence, and resume her play.)

これがこの章の9段落目です。ちょっとあとの13段落目から章の最後の26段落目のひとつ前の25段落までの母と娘の会話(ねちっこい語り手のコメントの段落は日本語訳からは落とします)。――

「おまえ。おまえはいったいなんなの」と母親は叫んだ。

「あたしお母さんのちいちゃなパールよ!」と子供は答えた。

・・・・・・

「おまえはわたしの子供なの、ほんとうに?」とへスターは尋ねた。

・・・・・・

「ええ、あたしちいちゃなパールよ!」と、おどけた身ぶりをやめずに子供はくりかえした。

「おまえはわたしの子供じゃない! おまえはわたしのパールじゃない」と母親はなかば遊ぶように言った。へスターは、深い苦悩の底にいるときにも戯れの衝動が起こることがあった。「教えてよ、おまえはなんなの? 誰がここへつれてきたの?」

「お母さんが教えてよ!」と子供は真剣に、へスターのそばに寄ってきて、膝にからだをすりつけた。「教えてちょうだい!」

「おまえの<天のお父さま>よ!」とへスター・プリンは答えた。

・・・・・・

「<彼> 〔天のお父さま〕じゃない!」とパールは強い調子で叫んだ。「あたしには<天のお父さま>なんかいない!」

「おだまり、パール、おだまり! そんなことを言ってはいけません!」と母親は呻き声を抑えながら言った。「<彼> 〔天のお父さま〕が皆を世界に送ってくださったのです。わたしだって、おまえのお母さんだってです。だから、おまえならなおさらだわ! そうでないというなら、おまえのような、ヘンな、妖精のような子は、どこから来たのです?」

「教えて、教えて!」とパールはくりかえしたが、もはや本気ではなくて、笑いながら床のうえを跳ねていた。「お母さんなら知っているはず!」

("Child, what art thou?" cried the mother.

"Oh, I am your little Pearl!" answered the child.

But while she said it, Pearl laughed, and began to dance up and down with the humoursome gesticulation of a little imp, whose next freak might be to fly up the chimney.

"Art thou my child, in very truth?" asked Hester.

Nor did she put the question altogether idly, but, for the moment, with a portion of genuine earnestness; for, such was Pearl's wonderful intelligence, that her mother half doubted whether she were not acquainted with the secret spell of her existence, and might not now reveal herself.

"Yes; I am little Pearl!" repeated the child, continuing her antics.

"Thou art not my child! Thou art no Pearl of mine!" said the mother half playfully; for it was often the case that a sportive impulse came over her in the midst of her deepest suffering. "Tell me, then, what thou art, and who sent thee hither?"

"Tell me, mother!" said the child, seriously, coming up to Hester, and pressing herself close to her knees. "Do thou tell me!"

"Thy Heavenly Father sent thee!" answered Hester Prynne.

But she said it with a hesitation that did not escape the acuteness of the child. Whether moved only by her ordinary freakishness, or because an evil spirit prompted her, she put up her small forefinger and touched the scarlet letter.

"He did not send me!" cried she, positively. "I have no

Heavenly Father!"

"Hush, Pearl, hush! Thou must not talk so!" answered the mother, suppressing a groan. "He sent us all into the world. He sent even me, thy mother. Then, much more thee! Or, if not, thou strange and elfish child, whence didst thou come?"

"Tell me! Tell me!" repeated Pearl, no longer seriously, but laughing and capering about the floor. "It is thou that must tell me!"

But Hester could not resolve the query, being herself in a dismal labyrinth of doubt. She remembered—betwixt a smile and a shudder—the talk of the neighbouring townspeople, who, seeking vainly elsewhere for the child's paternity, and observing some of her odd attributes, had given out that poor little Pearl was a demon offspring: such as, ever since old Catholic times, had occasionally been seen on earth, through the agency of their mother's sin, and to promote some foul and wicked purpose. Luther, according to the scandal of his monkish enemies, was a brat of that hellish breed; nor was Pearl the only child to whom this inauspicious origin was assigned among the New England Puritans.)

12720-20E382B3E38394E383BC.JPG)

Frederick C. Gordon, illust. The Scarlet Letter (p. 127)――母親の胸に付けられた A をめがけて花の矢を投げ続ける娘のパール・・・・・・えっと、このときに娘のパールは3歳なんで、ちょっと画は大きすぎるように思いますが、ともあれ、このときに上記の母と娘の会話は起こります。

え? 地の父が出てこない? そーなんです。記憶のなかには対比的にあったのですが・・・・・・。ま、隠蔽されている、ということで・・・・・・。と逃げようと思うと、実は最後の段落で、ホーソーンは意外な「父」に言及します(原文は上の英語の最後のパラグラフ)。――

けれどもヘスターは疑惑の陰鬱な迷宮に入り込んで、質問に答えることができなかった。彼女は近隣のひとびとの話していたことを――微笑とも身震いともつかない状態で――思い起こした。子供の父親がどこにも見つからないことと、この子供の奇妙な性質をいくらか見聞きしていたので、ひとびとは、かわいそうな小さなパールは悪魔の子 (demon offspring) だと言いふらしていた。昔のカトリックの時代から、母親の罪のせいでときおりそんな子供が生まれ、なにか汚れた邪悪な計画を促進するために地上に送られてくるといわれる。ルターも反対派の修道僧の悪口によれば、地獄の申し子であり、ニューイングランドのピューリタンたちのあいだではパールもこの不吉な起源に帰せられる唯一の子供というわけではなかったのである。

ここでの想像力は天上と地上、というにとどまらず、地下へ、地獄へと降下して、神と悪魔の対立の緊張状態のなかに人の世たる地上がイメジされているのでした。

午後4時追記――

えーと、ホーソーンのほうがルイーザ・メイ・オールコットよりもよかれあしかれ観念的で、地上的なできごとの背後に神と悪魔(の構図)を透かし見る、だから(はしょって言うと)ホーソーンはロマンス的で、オルコットはノヴェル的なリアリズムへさしかかっている、ということを言いたいわけではないです(言ってもいいけど)。オルコットをこのごろ読んでいるのですけれど、いっぽうで父親と親和的だったアメリカ超絶主義の影響とともに、やっぱり父の代で親交があったホーソーンの影響を、作家的にむしろ前者より多分に、受けている感じがします。それは具体的には、フロイト以前にフロイト的といわれるホーソーンの psychological な人間理解です。話が長くなりそうなのでやめますけれど、たとえば、悪魔と契約するとか悪魔や悪霊が憑依するとかいう「物語」が、人間の心(魂)のうちなる悪魔(ヒユだけど)みたいなところに変化していく、結果、ゴシック的超自然が心理化・人間内在化するというような流れ。

////////////////////////////////////////

Nathaniel Hawthorne, The Scarlet Letter 初版 (Boston: Ticknor, Reed, and Fields, 1850) のE-text @ Internet Archive <http://www.archive.org/stream/letterromscarlet00hawtrich#page/n5/mode/2up>

The Scarlet Letter: A Romance by Nathaniel Hawthorne. Vignette Edition, with One Hundred New Illustrations by Frederick C. Gordon. New York: Frederick A. Stokes, 1893. <http://www.archive.org/stream/romancescarlet00hawtrich#page/n5/mode/2up>

E-text at Project Gutenberg <http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/33/pg33.html>

シュワー――フランシスとフランセス Schwa: Francis and Frances [Marginalia 余白に]

Frances というのは女の名前で、『秘密の花園』と『白いひと』を書いた女性作家 Frances Hodgson Burnett やヨーロッパの神秘主義思想史の卓越した研究者であったFrances Yates が個人的には親しい。Francis というのは男の名前で、個人的に親しいのは・・・・・・うーん、作家のFrancis Scott Fitzgerald とアメリカ国歌を作曲した Francis Scott Key ですか(ちょっとわざとらしー)。

Frances と Francis の e と i の母音(字)部分は、普及している発音記号だとどちらも同じ /ə/ で表記されます。モーリちゃんの父は英語音声学は何十年も前に習ったキリで、あとドイツ語やスペイン語の学生と一緒に実験音声学の機材を作り損ねてしょうがなく秋葉原まで修理に行ったりとか、音声関係苦手なんすけど、/ə/を「シュワー」と呼び、「曖昧母音」と称するというくらいの知識はあったつもりでした。

んが、ウィキペディアを見ると、曖昧母音と等号で結ばれるのではないことを数十年ぶりに知りました。――

シュワー(schwa)とは母音の一つ。またはその音を表す音声記号・文字 ə のことを指す。ただし、その対象には二つのものがある。同じ記号で表されても両者は同じではない。

一つは国際音声記号によって定められた中舌で口の開きの度合いも中間的な中央母音 [ə] を指す。これを中舌中央母音(なかじた・ちゅうおうぼいん)または中段中舌母音(ちゅうだん・なかじたぼいん)という。

またもう一つは曖昧母音(あいまいぼいん)とも呼ばれ、各言語において見られるはっきりとした特徴のない中性的な母音のことをいう。言語によっては前述の中舌中央母音 [ə] でないこともあるが、音素表記では /ə/ と書かれることが多い。

この曖昧母音を音素としてもつ言語の発音を日本語で表記する場合、「ア段」または「ウ段」「オ段」で表記される。

〔「シュワー - ウィキペディア」〕

ふーん。中段なんたら母音 (mid-central vowel) と曖昧母音は違うので、前者については「シュワー」と言わずに中舌中央母音とか中段中舌母音と呼ぶみたいですね。

まー、なんだかよくわからないけれど、英語の Wikipedia のFrancis の記事を見ると、冒頭の記述はこんな感じ――

Francis is a French and English first name and a surname of Latin origin.

Francis is a name that has many derivatives in most European languages. The female version of the name in English is Frances, and (less commonly) Francine. (For most speakers, Francis and Frances are homophones or near homophones; a popular mnemonic for the spelling is "i for him and e for her".) The name Fran is a common diminutive for Francis, Frances and Francine. In Italian and Spanish, the form Fran is mostly used for boys and men, while Franci is more common for girls and women. 〔"Francis -Wikipedia"〕

つまり、この名前の英語の女性版 (female version) は Frances (あと Francine)で、たいがいの話者にとって Francis と Frances は "homophones" 〔同音語〕あるいは "near homophones" 、それで、よくある区別法(記憶法)は彼に (him) はi で彼女に (her) は e。

Francis の発音のIPA (国際音声記号〔字母〕)表記は /fræncəs/ 、Frances のほうは(も) /fræncəs/(æ のストレス省略)。あー、いまリーダーズ英和をみたら、どっちも「フランシス」と表記されてました。

さて、第一に発音記号が同一だからって現実に同一の発音とは限らないということがあります。それを前もって言っておきます。

そして、日本では表記を微妙に変えることによって意味や指示対象の違いを示すというあたりまえといえばあたりまえですが、でも美しくオシャレな伝統がありました(し、あります)。バレエ〔舞踏の〕とバレー〔ボール〕とか、アイロン〔家政の〕とアイアン〔ゴルフの〕とか、シャベル〔庭の〕とショべル〔建築の〕とか(最後の例は英語 shovel の発音表記としては「シャ」が圧倒的に正しいのだけれど)。

で、フランシスは男、フランセスは女、という了解が昔はあったように思われます。あるいは――聖フランシスとかサンフランシスコとかいう男性表記が確立された時点で、意識的にか無意識的にか心あるひとびとが女性を「フランセス」と表記して区別しようとした歴史があったように思われます。

ウィキペディアの「シュワー」の記事の、「この曖昧母音を音素としてもつ言語の発音を日本語で表記する場合、「ア段」または「ウ段」「オ段」で表記される。」という記述は、なんたら母音と曖昧母音の新たな区別が自分にはよくわからないので、英語の場合のたとえば Watson の "o" がどっちなんだかわからないので、結果よくわからないのだけれど、ホームズの相棒の「ワトソン」「ワトスン」という表記にカラムように思われます。

しかし、フランシスとフランセスは「イ段」または「オエ段」なんだが・・・・・・なんだかなー。

ひるがえって、発音記号が同じだから、どっちも「フランシス」で統一するべきだ、というのはおかしいと思うわけです、絶対に。

"The IPA Symbol for the Schwa" image via "Schwa - Wikipedia" <http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Schwa>

///////////////////////

むかしの関連記事(?)――

「July 15 ユニセックスな名前と発音の微妙な問題 Pronouncing Leslie, a unisex name [名前 names]」 (2008.7.15@カリフォルニア時間)

紬(Tsumugi) に恥をさらした後日談 [Marginalia 余白に]

紬(Tsumugi) - 外国人名対訳辞書(自動編纂)、q.v. 「グイド・レニ」 retrieved on Sept. 8, 2010.

「紬(Tsumugi) - 外国人名対訳辞書(自動編纂)に恥をさらす 」を書いたあと、3週間ほどたった今日の朝、開いてみたら、Guide Reni の件数がこの記事自体のために3件増えていた(下の [03][04][05])。精確に書くと、「AND数 6件, 調査数 2件, 確認数 2件, 推定数 2件.

」→「AND数 20件, 調査数 7件, 確認数 7件, 推定数 7件. 」――

Tsumugi は外国語固有「人名に対して、すでにカタカナ訳があるかどうか、複数のカタカナ訳がある場合は、それらの使用や定着の度合」を示すことを目的とする自動生成辞書である。自動生成だからって、「グイド・レニを誤って Guide Reni と綴ったら」と綴った箇所を根拠にグイド・レニの原語は Guido Reni ではなくて Guide Reni かも、という(個人的には恥さらしの、一般的には虚偽の)印象を増やしてもいいのだろうか。

しかも、不条理を感じつつも自らの反省とともに確認したら、わたくしめはちゃんと過去記事を誠意をもって訂正しておりました(えへん)――上が3月10日の、下が2月16日――

「大天使ミカエルが踏みつぶすものたち(1) Those Whom the Archangel Michael Treads (1) [ひまつぶし]」

よくわからないのは、(1) 元記事を情報的に反芻するブログランキングとかブログ検索とかと紬の確率設定基準の関係、(2) なんで2月16日の「大天使ミカエルのこと」のほうは refer されないか、なのですけれど、まあ、あまたある検索エンジン同様の深遠な秘密があるのかもしれません。あと (3) 同じソースからは2度とはカウントしないのかしら。

それにしても、元の記事を誠意をもって訂正するとともに、間違っていたことを訂正する記事を書いた行為に対して、この仕打ちはなんなんだw。違うっちゅうとんのに~。

で、こういうふうにまた書いたものが上記(3) みたいなことで反映されないかどうか、ジッと見守ってみようと思う日曜の昼下がりだったのでした。

Guide Reni のほうだったらされないほうがいいのかも。だって、なるほど紬の主旨はある原語の日本語表記の特定にあるかもしらんけど、記述としてはカタカナ日本語表記の原語は何かという情報も与えているわけで、間違った原語を指示する数値が上がってしまったら困りますよね。

紬(Tsumugi) - 外国人名対訳辞書(自動編纂)、q.v. 「グイド・レニ」 retrieved on Oct. 3, 2010.

あー、また、である調が途中からですますに変わってしまったであります。

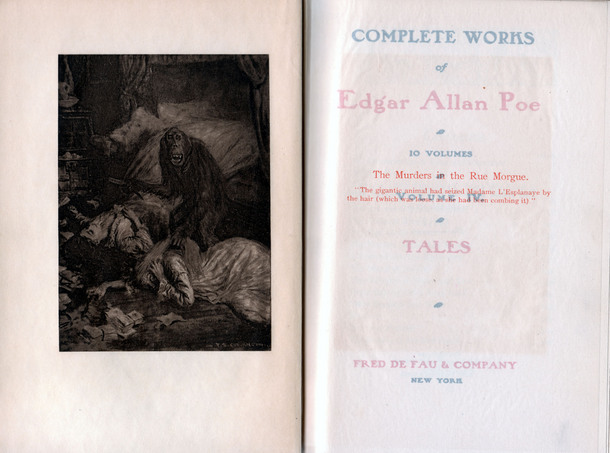

「エドガー・A・ポーの死」――N・P・ウィリスのポー追悼文 "Death of Edgar A. Poe" (1849) by Nathaniel P. Willis [Marginalia 余白に]

ニューヨークの新聞・雑誌編集者だったナサニエル・P・ウィリス Nathaniel Parker Willis, 1806-67 は1844年にポーを『イヴニング・ミラー』紙の "paragrapher" (一種の編集助手――ウィリスの文章だと "sub-editor")として雇っていて、3つほど歳のちがうポーと親交がありました。手紙のやりとりも続けていました。ポーはエッセイ「ニューヨーク市の文人たち」や「直筆署名」でウィリスをとりあげていることはポー事典も指摘しています。でも指摘していないことだけれど、ウィリスがあてこすられている短篇小説もいくつもあるみたいです。そのあてこすりは、しかし、友人関係を壊すほどのものではなかった(とはウィリスは受け止めなかった)ようです。

ポーが1849年の10月7日に亡くなって、文学的遺産管財人となるルーファス・ウィルモット・グリズウォルド Rufus Wilmot Griswold, 1815-57 は、ポーに対する誹謗中傷をしだいに募らせていくわけですけれど、N・P・ウィリスは、グリズウォルドを中心とする人身攻撃に異を唱えたひとりでした(女友達のセイラ・ホイットマン――「イタコのセイラ」参照――がもうひとり)。

1849年10月20日号の『ホーム・ジャーナル Home Journal』でウィリスはポーの追悼文を書きますが、グリズウォルドの早速の中傷文章を引用して反駁しています。――

The ancient fable of two antagonistic spirits imprisoned in one body, equally powerful and having the complete mastery by turns-of one man, that is to say, inhabited by both a devil and an angel seems to have been realized, if all we hear is true, in the character of the extraordinary man whose name we have written above. Our own impression of the nature of Edgar A. Poe, differs in some important degree, however, from that which has been generally conveyed in the notices of his death. Let us, before telling what we personally know of him, copy a graphic and highly finished portraiture, from the pen of Dr. Rufus W. Griswold, which appeared in a recent number of the Tribune:

“Edgar Allen Poe is dead. He died in Baltimore on Sunday, October 7th. This announcement will startle many, but few will be grieved by it. The poet was known, personally or by reputation, in all this country; he had readers in England and in several of the states of Continental Europe; but he had few or no friends; and the regrets for his death will be suggested principally by the consideration that in him literary art has lost one of its most brilliant but erratic stars. (エドガー・アランポーが亡くなった。10月7日の日曜日にボルティモアで死去。この通知は多くの人々を驚かせるだろうが、それで悲しむ者はごく少ないだろう。 詩人は、個人として、また評判によって、この国じゅうに知られていた。イギリスと、ヨーロッパ大陸のいくつかの国に読者をもっていた。しかし、彼にはほとんど、あるいはまったく友人がいなかった。・・・・・・)

“His conversation was at times almost supramortal in its eloquence. His voice was modulated with astonishing skill, and his large and variably expressive eyes looked repose or shot fiery tumult into theirs who listened, while his own face glowed, or was changeless in pallor, as his imagination quickened his blood or drew it back frozen to his heart. His imagery was from the worlds which no mortals can see but with the vision of genius. Suddenly starting from a proposition, exactly and sharply defined, in terms of utmost simplicity and clearness, he rejected the forms of customary logic, and by a crystalline process of accretion, built up his ocular demonstrations in forms of gloomiest and ghastliest grandeur, or in those of the most airy and delicious beauty, so minutely and distinctly, yet so rapidly, that the attention which was yielded to him was chained till it stood among his wonderful creations, till he himself dissolved the spell, and brought his hearers back to common and base existence, by vulgar fancies or exhibitions of the ignoblest passion.

“He was at all times a dreamer―dwelling in ideal realms―in heaven or hell―peopled with the creatures and the accidents of his brain. He walked the streets, in madness or melancholy, with lips moving in indistinct curses, or with eyes upturned in passionate prayer (never for himself, for he felt, or professed to feel, that he was already damned, but) for their happiness who at the moment were objects of his idolatry; or with his glances introverted to a heart gnawed with anguish, and with a face shrouded in gloom, he would brave the wildest storms, and all night, with drenched garments and arms beating the winds and rains, would speak as if the spirits that at such times only could be evoked by him from the Aidenn, close by whose portals his disturbed soul sought to forget the ills to which his constitution subjected him―close by the Aidenn where were those he loved―the Aidenn which he might never see, but in fitful glimpses, as its gates opened to receive the less fiery and more happy natures whose destiny to sin did not involve the doom of death. (彼はいつも夢見るひとだった――想像の領域に住んでいた――天国にせよ地獄にせよ――一緒にいたのは自分の脳髄がこしらえた創造物と出来事だった。彼が道を歩くときは、狂気に駆られているか憂鬱に落ちているのか、その唇は不分明な呪詛を吐いてうごめき、うわむきの目が何を情熱的に祈っているのかといえば(自分自身のためでは決してなく、というのも彼は既に地獄落ちの宿命にあると感じていたか感じていると公言していたからで)自分がそのときに崇拝していた偶像たちの幸福のためであった。あるいはまた彼の視線は苦悩でさいなまれる心に内向化され、憂鬱の経帷子に顔を包んだまま、彼は、いかなる激しい嵐にも向かっていった。そして一晩じゅう、びしょ濡れの衣服をまとい両手で風雨を振り払って、こうした時に彼によってあエイデン〔天国〕から呼び出されたとしか思われぬ霊たちにむかってであるかのように話すのだった。天国の扉の近くで、彼の悩める魂はその体が自分を従えさせる悪を忘れようと試みた――彼の愛する者たちがいたエイデンの近くで――彼自身は発作的な一瞥によって以外は垣間見ることの決してかなわない天国であった。なぜなら天国の門が開かれて迎え入れるのはそれほど火のような激情に駆られぬ、もっと幸せな性質のひとびとであって、彼らの罪に対する宿命は死の運命を含んではいなかったからである。)

“He seemed, except when some fitful pursuit subjugated his will and engrossed his faculties, always to bear the memory of some controlling sorrow. The remarkable poem of ‘The Raven’ was probably much more nearly than has been supposed, even by those who were very intimate with him, a reflection and an echo of his own history. He was that bird’s

“ ‘unhappy master whom unmerciful Disaster

Followed fast and followed faster till his songs one burden bore―

Till the dirges of his Hope that melancholy burden bore

Of ‘Never-never more.’

“Every genuine author in a greater or less degree leaves in his works, whatever their design, traces of his personal character: elements of his immortal being, in which the individual survives the person. While we read the pages of the ‘Fall of the House of Usher,’ or of ‘Mesmeric Revelations,’ we see in the solemn and stately gloom which invests one, and in the subtle metaphysical analysis of both, indications of the idiosyncrasies of what was most remarkable and peculiar in the author’s intellectual nature. But we see here only the better phases of his nature, only the symbols of his juster action, for his harsh experience had deprived him of all faith in man or woman. He had made up his mind upon the numberless complexities of the social world, and the whole system with him was an imposture. This conviction gave a direction to his shrewd and naturally unamiable character. Still, though he regarded society as composed altogether of villains, the sharpness of his intellect was not of that kind which enabled him to cope with villany, while it continually caused him by overshots to fail of the success of honesty. He was in many respects like Francis Vivian in Bulwer’s novel of ‘The Caxtons.’ Passion, in him, comprehended -many of the worst emotions which militate against human happiness. You could not contradict him, but you raised quick choler; you could not speak of wealth, but his cheek paled with gnawing envy. The astonishing natural advantages of this poor boy―his beauty, his readiness, the daring spirit that breathed around him like a fiery atmosphere―had raised his constitutional self-confidence into an arrogance that turned his very claims to admiration into prejudices against him. Irascible, envious―bad enough, but not the worst, for these salient angles were all varnished over with a cold, repellant cynicism, his passions vented themselves in sneers. There seemed to him no moral susceptibility; and, what was more remarkable in a proud nature, little or nothing of the true point of honor. He had, to a morbid excess, that, desire to rise which is vulgarly called ambition, but no wish for the esteem or the love of his species; only the hard wish to succeed-not shine, not serve -succeed, that he might have the right to despise a world which galled his self-conceit.

“We have suggested the influence of his aims and vicissitudes upon his literature. It was more conspicuous in his later than in his earlier writings. Nearly all that he wrote in the last two or three years-including much of his best poetry-was in some sense biographical; in draperies of his imagination, those who had taken the trouble to trace his steps, could perceive, but slightly concealed, the figure of himself.”

Apropos of the disparaging portion of the above well-written sketch, let us truthfully say:―

Some four or five years since, when editing a daily paper in this city, Mr. Poe was employed by us, for several months, as critic and sub-editor. This was our first personal acquaintance with him. He resided with his wife and mother at Fordham, a few miles out of town, but was at his desk in the office, from nine in the morning till the evening paper went to press. With the highest admiration for his genius, and a willingness to let it atone for more than ordinary irregularity, we were led by common report to expect a very capricious attention to his duties, and occasionally a scene of violence and difficulty. Time went on, however, and he was invariably punctual and industrious. With his pale, beautiful, and intellectual face, as a reminder of what genius was in him, it was impossible, of course, not to treat him always with deferential courtesy, and, to our occasional request that he would not probe too deep in a criticism, or that he would erase a passage colored too highly with his resentments against society and mankind, he readily and courteously assented-far more yielding than most men, we thought, on points so excusably sensitive. With a prospect of taking the lead in another periodical, he, at last, voluntarily gave up his employment with us, and, through all this considerable period, we had seen but one presentment of the man-a quiet, patient, industrious, and most gentlemanly person, commanding the utmost respect and good feeling by his unvarying deportment and ability.

Residing as he did in the country, we never met Mr. Poe in hours of leisure; but he frequently called on us afterward at our place of business, and we met him often in the street-invariably the same sad mannered, winning and refined gentleman, such as we had always known him. It was by rumor only, up to the day of his death, that we knew of any other development of manner or character. We heard, from one who knew him well (what should be stated in all mention of his lamentable irregularities), that, with a single glass of wine, his whole nature was reversed, the demon became uppermost, and, though none of the usual signs of intoxication were visible, his will was palpably insane. Possessing his reasoning faculties in excited activity, at such times, and seeking his acquaintances with his wonted look and memory, he easily seemed personating only another phase of his natural character, and was accused, accordingly, of insulting arrogance and bad-heartedness. In this reversed character, we repeat, it was never our chance to see him. We know it from hearsay, and we mention it in connection with this sad infirmity of physical constitution; which puts it upon very nearly the ground of a temporary and almost irresponsible insanity.

The arrogance, vanity, and depravity of heart, of which Mr. Poe was generally accused, seem to us referable altogether to this reversed phase of his character. Under that degree of intoxication which only acted upon him by demonizing his sense of truth and right, he doubtless said and did much that was wholly irreconcilable with his better nature; but, when himself, and as we knew him only, his modesty and unaffected humility, as to his own deservings, were a constant charm to his character. His letters, of which the constant application for autographs has taken from us, we are sorry to confess, the greater portion, exhibited this quality very strongly.

In one of the carelessly written notes of which we chance still to retain possession, for instance, he speaks of “The Raven”―that extraordinary poem which electrified the world of imaginative readers, and has become the type of a school of poetry of its own―and, in evident earnest, attributes its success to the few words of commendation with which we had prefaced it in this paper. ―It will throw light on his sane character to give a literal copy of the note:―

“FORDHAM, April 20, 1849.“My dear Willis:―The poem which I inclose, and which I am so vain asto hope you will like, in some respects, has been just published in apaper for which sheer necessity compels me to write, now and then. It pays well as times go-but unquestionably it ought to pay ten prices;for whatever I send it I feel I am consigning to the tomb of theCapulets. The verses accompanying this, may I beg you to take out ofthe tomb, and bring them to light in the ‘Home journal?’ If you can oblige me so far as to copy them, I do not think it will be necessaryto say ‘From the――, ―that would be too bad;―and, perhaps, ‘From a late――paper,’ would do.

“I have not forgotten how a ‘good word in season’ from you made ‘TheRaven,’ and made ‘Ulalume’ (which by-the-way, people have done me thehonor of attributing to you), therefore, I would ask you (if I dared)to say something of these lines if they please you.

“Truly yours ever,

“EDGAR A. POE.”

In double proof of his earnest disposition to do the best for himself, and of the trustful and grateful nature which has been denied him, we give another of the only three of his notes which we chance to retain:―“FORDHAM, January 22, 1848.

“My dear Mr. Willis:―I am about to make an effort at re-establishingmyself in the literary world, and feel that I may depend upon youraid.

“My general aim is to start a Magazine, to be called ‘The Stylus;’ but it would be useless to me, even when established, if not entirelyout of the control of a publisher. I mean, therefore, to get up ajournal which shall be my own at all points. With this end in view, I must get a list of at least five hundred subscribers to begin with;nearly two hundred I have already. I propose, however, to go Southand West, among my personal and literary friends―old college andWest Point acquaintances―and see what I can do. In order to get themeans of taking the first step, I propose to lecture at the Society Library, on Thursday, the 3d of February, and, that there may be nocause of squabbling, my subject shall not be literary at all. I have chosen a broad text―‘The Universe.’

“Having thus given you the facts of the case, I leave all the restto the suggestions of your own tact and generosity. Gratefully, mostgratefully,

“Your friend always,

“EDGAR A. POE.”

Brief and chance-taken as these letters are, we think they sufficiently prove the existence of the very qualities denied to Mr. Poe―humility, willingness to persevere, belief in another’s friendship, and capability of cordial and grateful friendship! Such he assuredly was when sane. Such only he has invariably seemed to us, in all we have happened personally to know of him, through a friendship of five or six years. And so much easier is it to believe what we have seen and known, than what we hear of only, that we remember him but with admiration and respect―these descriptions of him, when morally insane, seeming to us like portraits, painted in sickness, of a man we have only known in health.

But there is another, more touching, and far more forcible evidence that there was goodness in Edgar A. Poe. To reveal it we are obliged to venture upon the lifting of the veil which sacredly covers grief and refinement in poverty; but we think it may be excused, if so we can brighten the memory of the poet, even were there not a more needed and immediate service which it may render to the nearest link broken by his death.

Our first knowledge of Mr. Poe’s removal to this city was by a call which we received from a lady who introduced herself to us as the mother of his wife. She was in search of employment for him, and she excused her errand by mentioning that he was ill, that her daughter was a confirmed invalid, and that their circumstances were such as compelled her taking it upon herself. The countenance of this lady, made beautiful and saintly with an evidently complete giving up of her life to privation and sorrowful tenderness, her gentle and mournful voice urging its plea, her long-forgotten but habitually and unconsciously refined manners, and her appealing and yet appreciative mention of the claims and abilities of her son, disclosed at once the presence of one of those angels upon earth that women in adversity can be. It was a hard fate that she was watching over. Mr. Poe wrote with fastidious difficulty, and in a style too much above the popular level to be well paid. He was always in pecuniary difficulty, and, with his sick wife, frequently in want of the merest necessaries of life. Winter after winter, for years, the most touching sight to us, in this whole city, has been that tireless minister to genius, thinly and insufficiently clad, going from office to office with a poem, or an article on some literary subject, to sell, sometimes simply pleading in a broken voice that he was ill, and begging for him, mentioning nothing but that “he was ill,” whatever might be the reason for his writing nothing, and never, amid all her tears and recitals of distress, suffering one syllable to escape her lips that could convey a doubt of him, or a complaint, or a lessening of pride in his genius and good intentions. Her daughter died a year and a half since, but she did not desert him. She continued his ministering angel―living with him, caring for him, guarding him against exposure, and when he was carried away by temptation, amid grief and the loneliness of feelings unreplied to, and awoke from his self abandonment prostrated in destitution and suffering, begging for him still. If woman’s devotion, born with a first love, and fed with human passion, hallow its object, as it is allowed to do, what does not a devotion like this-pure, disinterested and holy as the watch of an invisible spirit―say for him who inspired it?

We have a letter before us, written by this lady, Mrs. Clemm, on the morning in which she heard of the death of this object of her untiring care. It is merely a request that we would call upon her, but we will copy a few of its words―sacred as its privacy is―to warrant the truth of the picture we have drawn above, and add force to the appeal we wish to make for her:

“I have this morning heard of the death of my darling Eddie. . . . Can you give me any circumstances or particulars? . . . Oh! do not desert your poor friend in his bitter affliction! . . . Ask Mr. ――to come, as I must deliver a message to him from my poor Eddie. . . .

I need not ask you to notice his death and to speak well of him. I know you will. But say what an affectionate son he was to me, his poor desolate mother. . . .”

To hedge round a grave with respect, what choice is there, between the relinquished wealth and honors of the world, and the story of such a woman’s unrewarded devotion! Risking what we do, in delicacy, by making it public, we feel―other reasons aside―that it betters the world to make known that there are such ministrations to its erring and gifted. What we have said will speak to some hearts. There are those who will be glad to know how the lamp, whose light of poetry has beamed on their far-away recognition, was watched over with care and pain, that they may send to her, who is more darkened than they by its extinction, some token of their sympathy. She is destitute and alone. If any, far or near, will send to us what may aid and cheer her through the remainder of her life, we will joyfully place it in her bands.

茶色にした部分、何を言っているのかわからないけれど有名なグリズウォルドの人格攻撃の一節を訳したら疲れて力尽きました。とりあえずウィリスのテクストの細かいパンクチュエーション等は今年出た次の本におおむね従いました (pp. 94-99)(ただしグリズウォルドの引用は "Tribune [excerpts from the Ludwig obtuary follow]." というふうに省略されているので、他 (pp. 73-80 に収録の “"Death of Edgar Allan Poe" in New York Daily Tribune (1849) / "Ludwig" [Rufus Wilmot Griswold]”)から補いました)。――

Benjamin F. Fisher, ed. Poe in His Own Time: A Biographical Chronicle of His Life, Drawn from Recollections, Interviews, and Memoirs by Family, Friends, and Associates. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press, 2010. 312pp.

アシナガオジサンとハエ The Daddy Long-legs and the Fly [Marginalia 余白に]

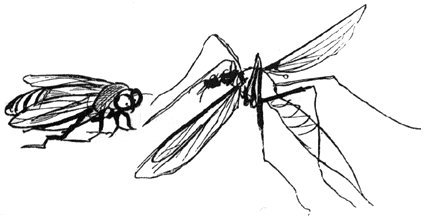

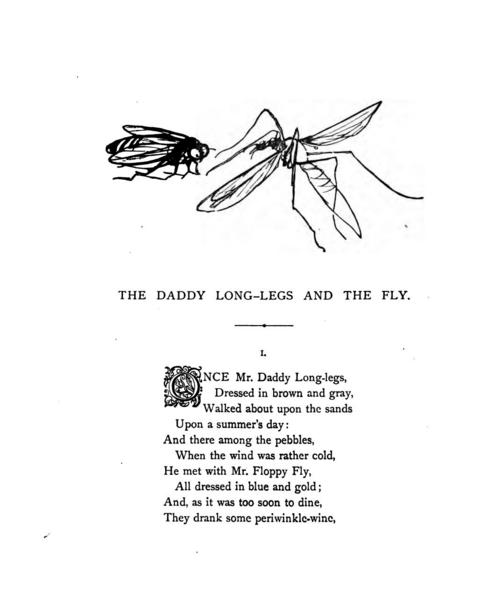

Wordnik 〔いちおー「ワードニックとワードテック Wordnik and Wordtheque 」参照〕 で daddy-long-legs, daddy longlegs, Daddy-Long-Legs などくりかえし引い(検索し)たおかげで、しばらく記事を書かなかった『あしながおじさん』に思いが募った正月八日です。